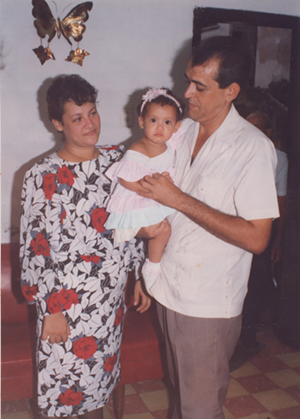

In November of 1999 my father took a plane from Cuba to Miami; 15 days later my mother and I followed him.

We immigrated legally, claimed by family already in the States who’d arrived 15 years earlier, after receiving a visa from the Diversity Immigration Visa Program — a visa lottery. But we were political refugees nonetheless.

We have not returned. Over the years, all of our close family members have managed to flee and resettle their lives in Chile, Spain and the States, so perhaps that’s why.

To my parents, Cuba remains the place where they lost their youth; my father to boarding-school field labor, a requirement of the “free” education, and my mother to at-home knitting because the government did not allow religious affiliates — members of a church — schooling past sixth grade, and she belonged to a Protestant church.

The second question I am asked after “What’s your nationality?” is whether I will now enjoy vacationing in Cuba. My answer is always no, not while there are Cubans still fleeing and the country is still under military control.

A few months back, sitting with my father at the Tax Collector’s office on Falkenburg Road in Tampa, we met a middle-aged couple newly arrived from Cuba. They shared with us the worsening conditions, the blackouts, the endless lines for rice, the water shortages and, curiously, the vast control over all the island by a group of high military officials and the Castros.

They weren’t wrong. The Grupo de Administración Empresarial S.A. of the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias (translated: Armed Forces Business Enterprises Group of the Revolutionary Armed Forces), a military-run and state-sponsored oligarchy and conglomerate created by Fidel Castro in the 1980s, now reportedly owns 60 to 70 percent of the country. At its head: General Luis Alberto Rodriguez, Raul Castro’s ex-son-in-law.

What this means is that when you go to Cuba, when you rent a car, a hotel room or purchase items from the shops in Old Havana — a popular tourism spot — you are funding GAESA.

They own hotel chains like the Gaviota and share management with foreign companies such as Melia, Iberostar and Starwood of the U.S. Marriott chain. They also own a shipping company, an airline, construction companies and the Almacenes Universales that controls the container traffic at the Port of Mariel, according to Havana Times, as well as two banks and all credit card and money transactions through Fincimex.

Their latest acquisitions included Cuba’s International Financial Bank and Habaguanex, the company in charge of all the state hotels, stores and eateries in Old Havana.

As former President Obama began to open up travel and trade with Cuba over the course of his two terms in office, I reacted with mixed emotions. On the one hand, I realized that the rollbacks would present Cubans with benefits denied them for years such as internet. Things that have been terribly limited would also benefit: access to poultry, grain, and agricultural products; the economy for workers in the private sector (small as it may be); improved infrastructure. I also considered that American journalists would now be able to report there, and vice versa.

Still, as a native Cuban who grew up in the U.S., hearing stories about families being deprived of milk once their children started school while those who worked for the government received cars, refrigerators and televisions, I wondered how much these new investments would reach the population.

According to a story earlier this month in the Washington Post, the results have been uneven. “Cuba’s authoritarian one-party system remains largely unchanged,” said the report, “and dissidents say government repression has increased over the past two years.” The paper stated that the leader of the island’s largest dissident group, Jose Daniel Ferrer of the Patriotic Union of Cuba, called this month in a letter to Trump for ‘maximum reversal of some policies that only benefit the Castro regime.’”

The Havana Times has also reported on the governmental insufficiencies affecting the country, especially in poor neighborhoods like Alamar. Agencies receiving the largest budgets are especially neglectful, such as the communales, or trash collectors.

“There’s a lack of public interest in what is happening in the street. This is somehow also part of the change; that Cubans are becoming individualistic,” 33-year-old artis Hamlet Lavastida told The Guardian, calling the apathy “passive dissidence.”

For those of us who have witnessed and been affected by an even greater, statewide apathy in Cuba, the news of President Trump’s partial restrictions on President Obama’s rollbacks came as a relief. These new restrictions target the conglomerate GAESA, but allow private small businesses to continue flourishing under the newfound tourism.

“Trump’s proposed changes are some of the wisest and most level-headed announcements of his presidency,” the Florida Times-Union’s editorial board wrote last week. Much as it pains me to admit it, I agree.

I have little to gain by going to Cuba. I will not enjoy myself at beautiful resorts that my Cuban counterparts are not allowed to visit, much less are able to afford, then return to my comforts here. To me, that would be immoral.

Nonetheless, I do not condemn tourism; many of my own family members have returned and stayed in their families’ homes. So if you go, here’s what I ask: Know where you are spending, who it is benefiting, and if possible, stay in the private sector.

Lis Casanova came to Miami from Bejucal, part of the Mayabeque Province, when she was 5. She’s the A&E summer intern at Creative Loafing and a senior at USF St. Petersburg, where she’s the copy editor at the Crow’s Nest.

Still, as a native Cuban who grew up here, hearing stories about children and their families being deprived milk once they started school, while those who worked for the government received things like cars, refrigerators and televisions, made me wonder how much these new investments would reach the population.

“The results have been uneven. Cuba's authoritarian one-party system remains largely unchanged, and dissidents say government repression has increased over the past two years. Jose Daniel Ferrer, leader of the Patriotic Union of Cuba (UNPACU), the island's largest dissident group, called this month in a letter to Trump for ‘maximum reversal of some policies that only benefit the Castro regime’,” The Washington Post reported earlier this month.

The Havana Times has also reported about the governmental insufficiencies affecting the country, especially in poor neighborhoods like Alamar. Agencies receiving the largest budget are especially neglectful, such as the communales, or trash collectors.

“There’s a lack of public interest in what is happening in the street. This is somehow also part of the change; that Cubans are becoming individualistic,” Hamlet Lavastida, a 33-year-old artist told The Guardian, calling the apathy "passive dissidence.”

For those of us who have witnessed and been affected by an even greater, statewide apathy in Cuba, the news of President Trump's partial restrictions President Obama's rollbacks came as a relief. These new restrictions target the conglomerate GAESA, but allow private small businesses to continue flourishing under the newfound tourism.

“Trump’s proposed changes are some of the wisest and most level-headed announcements of his presidency,” the the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville editorial board wrote last week, and I agree (as much as it pains me to admit it).

I have little to gain by going to Cuba. I will not enjoy myself at beautiful resorts that my Cuban counterparts are not allowed to visit, much less can afford, then return to my comforts here; to me, that would be immoral.

Nonetheless, I do not condemn tourism; many of my own family have returned and stayed in their families' homes. So if you go, here's what I ask: Know where you are spending, who it is benefitting, and if possible, stay on the private sector.

Lis Casanova Rodriguez came to Miami from Bejucal, part of the Mayabeque Province, when she was five. She's the A&E summer intern at Creative Loafing and a senior at USF St. Petersburg, where she's the copy editor at the Crow's Nest.