My reaction to Steve Locke’s work started long before I saw it in person, when Gallery 221 director, Amanda Poss, sent me a link to one of Locke’s articles in the online art forum Hyperallergic .

In "What did you do on your sabbatical?" Locke writes about what happened during a year off from teaching, when the Massachusetts College of Art and Design professor intended to focus on his art.

Instead, the African-American artist faced a year-long barrage of highly publicized deaths of unarmed African Americans by police.

“I painted almost every day, and every day this parade of killing was on my television and radio and social media feed,” he writes. Eric Garner’s death was the first time he saw a black person get killed on television. NYPD Officer Daniel Pantaleo Garner choked Garner while arresting him for allegedly peddling illegal cigarettes on July 17, 2014. The unarmed Garner didn’t appear threatening when four officers tackled him. We heard him plead, over and over, “I can’t breathe!” The officers appear to violate two NYPD policies: placing Garner in a choke hold and then kneeling on his body. Garner suffered a heart attack in the ambulance and died in the hospital.

On April 12, 2015, Baltimore police arrested Freddie Gray for allegedly possessing an illegal switchblade. How do you rough someone up to such a degree that you sever their spine at the neck by 80%, they slip into a coma, and then die from spinal injuries and cardiopulmonary arrest seven days later?

“Images and video of Mr. Gray’s assault were ubiquitous, his cries of pain were broadcast and his hospitalization was shown on newscasts,” writes Locke. “A citizen was turned into an object before our eyes and no one was held accountable for his pain, his suffering, or his loss.”

By the end of 2015, more than 262 unarmed African Americans were either killed by police or died in police custody, according to Locke.

None of this prepared me for Locke’s Family Pictures exhibit.

At first, nothing seems awry. Brightly colored photographs circle the room. Each shows a historical photo in a mass-produced picture frame, sitting atop a 1960s-era Andre Bus coffee table. From a distance, the images aren’t clear.

“Always & Forever 1” looks like a black man sleeping in a chair. The image comes from James Allen’s book Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America, and the man in it is dead — murdered, set in a rocking chair, with a rod propping up his head.

Death grows more evident the more you look. We see a black man lynched in front of a crowd of white men. It makes me angry, and the words on the frame piss me off even more. Fun? Friends? Laughter? Happy? Joy? What the fuck?

I step to my right and see “Memories.” Here another black man hangs from a tree, his hands bound. The white people in the photograph watch, dressed in their Sunday best, as if attending an opera.

Another silver “Always and Forever” frame shows a man burnt to a crisp, hanging from a pole. Again, there is a crowd of passive onlookers. My teeth clench harder. In “Good Times, Good Friends,” a man is being burned in the foreground while a couple of twisted motherfuckers smile for the camera. “Who wouldn’t want to be us” shows a group lynching, with at least two men hanging from a post. More assholes smile for the camera.

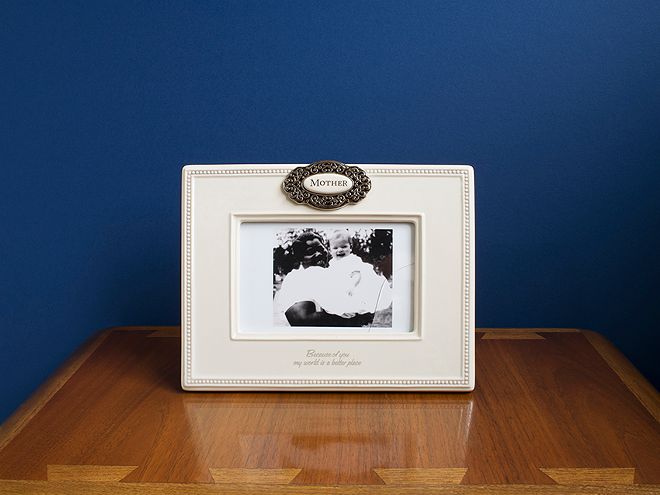

Finally, I catch a break. A smiling black woman holds a smiling white baby in “Mother.” Locke tells me this is the image most people request to buy. I can see why; it’s a shining ray of hope after a long darkness. But after seeing so much violence, there’s a part of me that doesn’t accept it. They look too happy. There must be something horrible I’m not seeing. I have a feeling of hope, of calm, and of suspicion all at the same time.

The next photo shows two hanged men in front of another crowd of onlookers. The frame reads, “I can’t believe we did that!” somehow equating murder with drunken shenanigans. Hey, remember that night we drank too much and I stole a bottle of rum? I can’t believe we did that.

As I approach the final picture, I read “Remember this day” in the frame. A black man is on his knees in a palmetto forest, hands bound, and back up against a pine tree.

Family Pictures is a horror show, but it’s not new. Locke’s exhibition reminds us that, this white-on-black violence on television? It’s not new. Not only is violence against African Americans a part of our history, so is the imaging of these injustices. The only thing that’s new is the technology.

Look at Allen’s Without Sanctuary, and you’ll see that the death of African Americans by lynching during the Jim Crow era was just as much of a show as police violence against African Americans is today. The only difference is that, back then, people weren’t carrying around video cameras in their pockets like we do now with our smartphones. Instead, they took photos and made them into postcards that they sent their friends and family with messages like, “this is the barbecue we had last night.”

But we can also use modern technology to return dignity to the victims of white-on-black violence. You can see this with Locke’s “Three Deliberate Grays for Freddie,” a memorial for Freddie Gray.

Instead of using modern technology to objectify Gray, Locke used it to memorialize him. He took three images of Gray frequently used by the media, and averaged the color of all the pixels in each photo to create shades of gray. You can see the three original photographs alongside the memorial at Gallery 221.

In “What did you do on your sabbatical?” Locke contrasts the reporting of African-American deaths with the reporting of Caucasian deaths. He specifically cites the example of two reporters, Alison Parker and Adam Ward, whose 2015 murder was filmed and uploaded onto social media by their killer. “To maintain the dignity of the victims, people begged the public not to watch the video,” writes Locke. But who maintains the dignity of African-American victims?

steve locke: the color of remembering | Gallery 221@HCC Dale Mabry Campus, 4001 West Tampa Bay Blvd., Tampa | Through Mar. 7 | 813-253-7386 | hccfl.edu/gallery221

Subscribe to Creative Loafing's weekly Do This newsletter to stay up-to-date on Tampa Bay's most eye-opening art exhibits.