African American Life and Family

Jan. 17-May 3, Museum of Fine Arts, 255 Beach Drive N.E., St. Petersburg, 727-896-2667, fine-arts.org

Gallery Talk with curatorial assistant Sabrina Hughes on Sun., Jan. 18, 3-4 p.m.

Cinema@theMFA: Through A Lens Darkly (2014, dir. Thomas Allen Harris) on Thurs., Jan. 29, 6:30 p.m.

More than a century ago, W. E. B. Du Bois set out to advance a proud image of black life in the U.S., dispelling stereotypes and counteracting racist caricatures by assembling an exhibition of 363 photographs of African Americans for the Paris Expo of 1900.

You’d like to think we live in a world where such a project would be superfluous. But in this season of somber reflection on the police killings of men and youth including Michael Brown (whose media representation as, alternately, an aggressor or a college-bound student, was bitterly contested in words and images) and solidarity campaigns including #BlackLivesMatter, the spirit of Du Bois’s project clearly remains urgent.

Beginning Saturday, St. Petersburg’s Museum of Fine Arts showcases African American Life and Family, an exhibition that mines the museum’s Dandrew-Drapkin donation of 14,000 photographs gifted in 2009 and 2010 to organize a display inspired by Du Bois’s endeavor. To create the homage, curatorial assistant Sabrina Hughes sifted through the photographs — not only those by known photographers, but many more vernacular photos accompanied by little, if any, information about their makers, their subjects, their places of origin or their reasons for existence — opening a window onto the lives of African Americans from the mid-1800s to the mid-20th century. The 46 images Hughes has selected span the gamut from silver gelatin prints to postcards, cartes-de-visite (affordable portraits on calling cards popular during the 1860s), a daguerreotype, a family photo album and a hand-colored “crayon portrait,” encompassing studio portraiture, journalism, and other discoveries, such as a group picture of the 300-plus members of a black battalion of engineers newly returned from France after World War II.

“When I started, I wasn’t sure what to expect. I was really happy with what we found,” she said as we walked through the partially installed exhibition earlier this week.

The peculiar thing about old photographs is how the weight of their meaning outstrips the delicacy of their physical substance. If you want to treasure a black life, try standing a few inches away from a hand-tinted tintype of a man whose steady gaze from warm brown eyes above a neatly trimmed beard meets yours, knowing that when his portrait was made he may have been a free man for less than a decade; the image’s title, based on available information about it, is “Former Slave, 1870.” Because tintype is a direct positive process, this man sat or stood where you are standing — directly across from the plate, though farther away from it — to have his picture taken, then tenderly imbued with soft tones of yellow, brown, black, white and blue. A whole plate tintype like this one (about 6 inches tall by 4 inches wide) is rarer than smaller ones, Hughes explains. It embodies a life valued deeply.

With the exception of the exhibition’s 20th century photograph, little is known about their compelling subjects. Postcards of individual people, shot in commercial portrait studios as one-off souvenirs, show a young scholar with a book under his arm, a smiling baby girl perched on a wooden chair, a older man in Union Army dress, a cluster of young, sharply dressed friends flirting and laughing. One photo Hughes finds intriguing is a group of six men identified only as workers at Yale University. While most are dressed in suits, one seated man wears a cardigan sweater and melancholic expression suggestive of a poet or an artist; the picture was made the year after Yale admitted its first black student. In another, a group of 15 lawyers and judges sits for a portrait inside a wood-paneled lodge, circa 1900. Though the photograph arrived with scant factual information, Hughes deduced their professions based on the gavel and American flag that one man holds, and drew insights from less literal clues.

“Their posture is incredibly confident,” she said. “It’s a hint toward the rich history of African Americans in law, post-Emancipation.”

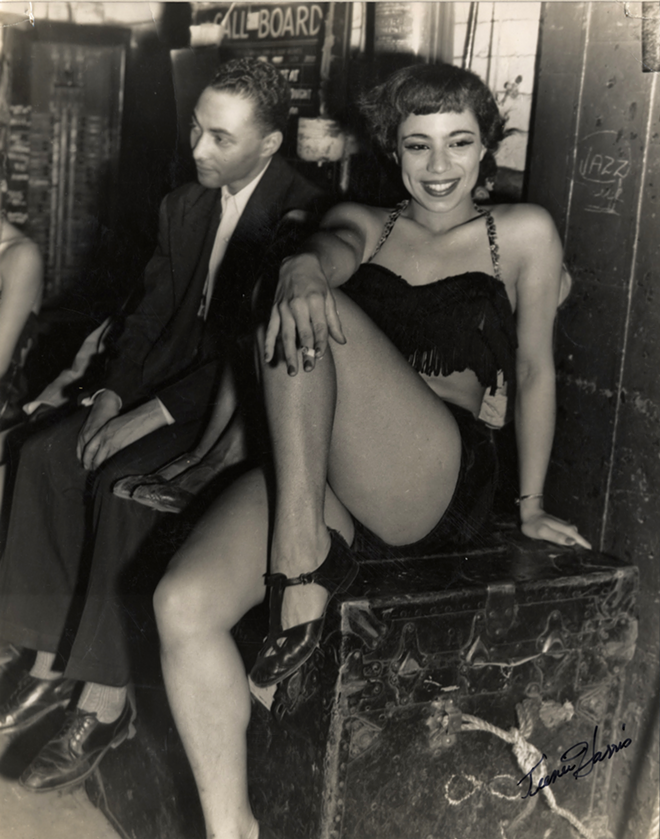

Such images are particularly affecting because they embody histories not yet thoroughly known or shared, stories that hinge on the preservation of and research into objects that an exhibition like this one performs. But there are also works in the show that do the opposite — celebrate famous African Americans and African American photographers who are revered within cultural circles. A silver-toned portrait of Booker T. Washington hangs alongside an image of the photographer, Addison Scurlock, whose Washington, D.C., studio was a mecca for black artists and luminaries from 1911 until the 1960s. (Along with Washington, he photographed Du Bois, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald and countless well-heeled D.C. residents.) To have your portrait made by Scurlock connoted that “you had arrived,” Hughes said. Working for black newspapers and magazines in Pittsburgh, Charles “Teenie” Harris captured portraits like one of a jazz club dancer in a fringed bikini, her identity unknown but her pin up-worthy beauty immortalized by the photographer, whose archive is a prized possession of the Carnegie Museum of Art.

The crowning glory is James VanDerZee’s Couple in “Raccoon Coats (1932).” The photograph depicts a stylish, affluent couple with full-length fur coats and a gleaming Cadillac Roadster during the Harlem Renaissance, the flowering of African American art, literature and music that overlapped with the Great Depression in the early 1930s. The only image borrowed for the exhibition — from the corporate collection of Trenam Kemker in St. Petersburg — it is often cited as an example of VanDerZee’s empowering photographs of black men and women. In the 1994 book Picturing Us: African American Identity and Photography, historian Deborah Willis described an encounter with the picture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that began her formal education in photography. “[VanDerZee’s] photographs broke the stereotype of Harlem during the Depression, and seeing the exhibition in 1969 made me want to recover the personalities captured within his frame,” she wrote.

It’s a testament to the enduring power of images that VanDerZee’s photograph, and the others in African American Life and Family at the MFA, inspires the same feeling today.