When you think of John Audubon, do you picture a man killing birds?

You should. And the Tampa Bay History Center’s latest exhibit, curated in partnership with the Audubon Florida’s Coastal Islands Sanctuaries, walks guests through the history of avian conservation, leaving you with an appreciation (if not agreement) for why conservationists like Audubon would kill birds.

“You have to kill a few birds to draw a few birds,” Rodney Kite-Powell, TBHC’s Touchton Map Library Director & Saunders Foundation Curator of History, says, and he’s only partly joking. “That’s how it was back then.”

It seems at odds with the notion of conservation, to kill a bird, and the trio of rifles on exhibit — along with taxidermied birds, both those standing on armature and skins of those not as artfully preserved — might give you pause; this is an Audubon-sanctioned exhibit?

Most definitely.

But back to “killing a few to draw a few” — why would that be a good idea, ever?

“We cannot use our current ethos of what is right to say what was right or wrong of that day,” Ann Paul, regional coordinator for Audubon Florida’s Coastal Islands Sanctuaries, says. “You have to understand the context of the day. When John James Audubon was working, he had two goals; one was to share the abundant natural history of this continent, which was a real interest to the Europeans... The other thing he was doing, he was trying to provide for his family. This was in a time, in the 1840s, where the resources were so abundant... no one was considering there was an end to those resources.”

Kite-Powell says naturalists also killed birds to help learn about them — and to help their counterparts across the pond learn about them, too.

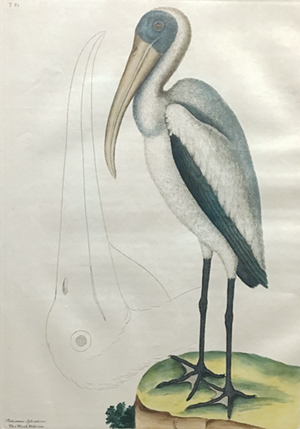

Consider the exquisite lone work in the exhibit by 18th-century naturalist Mark Catesby — the one pictured here. This spectacular imagining of a wood stork, called by Catesby a “wood pelican,” doesn’t give us an accurate look at what we know wood storks look like. That’s where the taxidermied birds —and the armatures that allow them those “lifelike” poses — came into play for the folks back in England, Catesby’s native country.

By the late 19th century, people, Paul says, realized “the exploitation of the natural resources of this country [was] reaching the point where they were no longer sustainable.”

And so we move to the next of the exhibit’s three parts: conservation. And that lesson is best taught by reddish egret skins on loan from Princeton.

Meet W. E. D. Scott, an ornithologist who came to Tampa Bay in 1880, where he collected (read: killed) nesting shorebirds in Clearwater Harbor. He returned again in 1886, expecting to collect more birds, but found instead a sobering reality.

“The colonies he found in 1880 were no longer there,” Paul says. And he told people what he’d found, raising awareness. “He... documented the effect of plume hunters on herons and other birds being shot for their feathers in Florida.”

Scott’s writing led to the founding of the society organizers would name, posthumously, after Audubon. Today, only about 400 nesting pairs of reddish egret remain in Florida, among an estimated 2,000 pairs throughout the U.S., according to the Society — but, if not for Scott, that number could well be nonexistent.

In the last leg of this exhibit, you’ll learn how the history, art and conservation all come together through partner organizations. Consider the spoonbill, so prevalent in Tampa Bay.

Or are they?

“People think we have a lot of them, but we don’t,” Paul says — less than 200 pairs remain. In this part of the exhibit, you can learn about current efforts from not only the Audubon Society, but Tampa Bay Watch, the Tampa Port Authority, Tampa Bay Estuary Program and others.

The history of conservation is a joint history, and sharing the art with TBHC patrons proves an excellent partnership.

“We considered it a tremendous opportunity to share information in the community,” Paul says. “It’s going to take continued vigilance on the part of citizens who care about... having the incredible legacy of our American heritage, in terms of the wildlife, the resources that are here. If we don’t care, we won’t have these animals in the future.”

Paul encourages people to call her at 813-623-6826 with any questions.