When Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness was first published in 1968, it garnered little attention. Now, on its 50th anniversary, it has earned its place on the bookshelf next to Thoreau, and its author, Edward Abbey, has become a cult figure, inspiring the likes of Carl Hiaasen with his quirky, satirical ideas on the rapid destruction of nature through modern technology, and highly unique ways to deal with it. Today Abbey’s voice remains relevant, and a new generation is listening.

In the celebrated book of essays, Abbey chronicles his rambles around his Utah desert home as a park ranger at the Arches National Monument, where he dwelt alone in a small government-issue trailer. He communed with the indigenous critters, which he viewed as far more hospitable than humans. He rescued hikers, and once found a dead man who had wandered away and succumbed to the August heat, a casualty of the desert. At night, he drove his battered pick-up into nearby Moab to hoist a few brews with local miners and cowboys, a brood usually too tired after a long day’s work to start any trouble (unlike city folk).

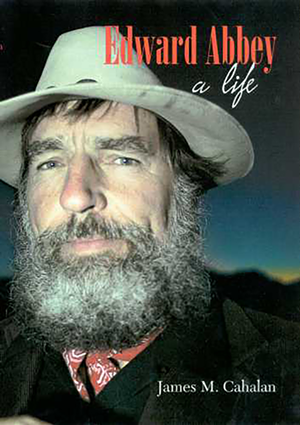

Even before his untimely death at sixty-two in 1989, Abbey was a legend. He was “Cactus Ed,” with his own self-created mystique. In the in-depth biography, Edward Abbey: A Life, James M. Cahalan burrows deeply into Abbey’s world, revealing as much as possible about the real man through letters, journals and interviews with those who knew him best. It’s not so much that Abbey told outright lies, just that he fit bits and pieces of his life together as he liked to see it.

Abbey binds together his three separate seasons in the Utah desert at Arches National Park — in1957, 1958, and again in 1962 — for Desert Solitaire, offering a prolonged view of the ongoing changes he witnessed in the desert. It’s a bit of creative license-taking. As for Abbey's claiming Home, Pennsylvania, as his birthplace, Cahalan reveals that he was born in 1927, and during his early childhood, deep in the Depression, his parents were constantly on the move in search of work. When the family finally settled in Home, Pennsylvania, Abbey was a teen. But the name Home is cozy, no doubt fulfilling a longing for permanence he missed in his younger years.

What makes Abbey’s desert narrative so memorable? He’s not the usual passive observer of nature’s beauty, he’s an active commentator, offended by parks department efforts to improve accessibility for the masses. No longer content to merely watch park engineers arrive with tractors and road-builders, Abbey is vocal…he hates the invasion thrust upon this ancient place of delicate arches, the stillness replaced with roaring bulldozers bringing roads to attract more tourists into the park with their motor homes, to litter, blare radios, and otherwise disturb the peace.

In Desert Solitaire’s chapter on “industrial tourism,” Abbey rants against this onslaught of development coming to his quiet corner. He bemoans the arrival of the “master campground,” where visitors now congregate together, and Comfort Stations brightly aglow frequently back up under the strain, while rangers at the new visitor’s center “… are going nuts answering the same three basic questions five hundred times a day: (1) Where’s the john? (2) How long does it take to see this place? (3) Where’s the Coke machine?”

But who was the real Edward Abbey? He’s been called an anarchist, a misogynist, a womanizer; he drank too much. He also spent time in the army, studied philosophy and music at the University of New Mexico in Taos, and he played the flute, Cahalan tells us. When his GI bill money gave out, he returned to Pennsylvania to work on a GE refrigerator assembly line with his brother. He finally earned a B.A. in philosophy and English in 1951, and a master's degree in philosophy in 1956; his master’s thesis explored the relationship between anarchism and violence.

In his two years as a military police officer in Italy, he was twice promoted but his anti-authoritarian attitude led to demotion and an honorable discharged as a private. He was married five times, but he was also a Fulbright scholar in Edenborough.

While in Taos, he worked as a reporter and a bartender, married his first of five wives, and was deposed as editor of a student paper for publishing an article titled, "Some Implications of Anarchy," The cover quotation stated "Man will never be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest,” which he attributed to Louisa May Alcott. Irate university officials seized all copies of the issue and kicked him off the paper. Friends remember his keen sense of humor.

Abbey spent a few months in the Everglades hunting gator poachers in the early ‘60s, when the park service sent him to a post near Homestead. He patrolled local highways in a cruiser, handing out warnings for speeders, trying his best to catch the legendary poacher known as Gator Roberts. But even with tips from a helpful roadside café waitress he’s unsuccessful, finding only taunting notes left by the notorious hunter.

His final novel, The Fool’s Progress: An Honest Novel is not an autobiography as many think, says Cahalan, but parts of it do reflect Abbey’s life. He loved to embellish, take thing to the most extreme, just to raise eyebrows. He was amused that the FBI believed some of his statements.

Cahalan’s in-depth examination of Abbey’s life won the 2002 Thomas J. Lyon Award from the Western Literature Association, and is considered his definitive biography. Other bios, and memoirs by friends are all worth reading, but Cahalan never met Abbey, hence his view is objective. As professor emeritus of English at Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP) in Indiana, Pennsylvania, near Abbey’s childhood home, he felt an affinity for this favorite literary son,

Desert Solitaire went out of print, and Abbey was still eking out a living to pay for child support and other necessities of life. He’d published two novels earlier, to moderate success, (The Brave Cowboy became a movie in 1962 with Kirk Douglas, released under the title Lonely Are the Brave) and he consigned this book of essays to the same fate. “Another bomb down the well,” he noted in his journal, but undaunted, he continued his writing, and his occupation as ranger.

In 1970, Desert Solitaire emerged in paperback, and suddenly everyone had a copy. It resonated with desert lovers, and quickly became an anthem, a revelation about the ongoing destruction in the West, much as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring sounded the alarm for pesticides a decade earlier. Abbey offered a new and stunning view of his world, a world of deserts and solitude, his seasons in the tin government trailer in Utah’s Arches National Monument, then a little-known spot with only trails, usually attracting only intrepid hikers, and not many of them…there were no facilities, no paved roads, and no motor vehicles allowed in the park. Suddenly, hoardes of desert-lovers, with dog-eared copies of his book, headed for the Arches.

In 1975 his famous novel, The Monkey Wrench Gang, appeared. Abbey’s protagonist (and perhaps his alter-ego), is a disgruntled Vietnam vet, the anti-hero George Washington Hayduke, who lurks about the Grand Canyon with a like-minded group of environmentalists plotting to sabotage the flooding of the beautiful Glen Canyon resulting in the now-infamous Lake Powell.

Abbey inspired a new cohort of activists with his novel, and in 1980 Earth First! emerged, a group dubbed eco-warriors. The premier effort…and still one of their most notorious actions…was “cracking” the Glen Canyon Dam in 1982, when a group climbed to the top of the controversial structure and dropped a sheet of black plastic down the face, simulating a giant crack in the unwelcome edifice. Abbey made a speech at the event. Cahalan recounts that while Abbey supported the efforts of Earth First!, he wanted no part of administrative, organizational work with the group, preferring to wander his beloved western wild lands and write. Cactus Ed loved the Southwestern deserts, but he also simply loved wilderness:

‘Wilderness. The word itself is music.

Wilderness. Wilderness… We scarcely know what we mean by the term, though the sound of it draws all whose nerves and emotions have not been irreparably stunned, deadened, numbed by the caterwauling of commerce, the sweating scramble for profit and domination.’ (Desert Solitaire)

Abbey is at once lyrical and poetic; after all, he played the flute and studied music. It’s difficult to choose quotable passages because, like a well-crafted symphony, it fits together as a whole, blending in a delicious harmony.

As the anarchist, he rebelled against the onslaught of progress at the expense of nature’s beauty, as he clearly portrays in his infamous character, Hayduke. He bristled against the construction of the hydroelectric dams that allowed new colonies to spring up in the dry, waterless deserts of the Southwest. He joked about burning billboards.

As his fame grew, Abbey was much in demand on the lecture circuit, where he usually played “Cactus Ed” to the hilt, amusing audiences with outrageous tales of his desert adventures. His fans adored him; women wrote him letters, wanted to meet him. But he was also a scholar, who quietly loved the music of Bartok, read classic poetry and philosophy. At his creative writing class, filled with suntanned students in hiking boots for the first session, he appeared professorial, and announced a rigorous schedule requiring well-researched papers, and lots of reading; at the second session, most of those pupils were gone because they expected the raucous Cactus Ed. Abbey mused, “This is more like it,” as he surveyed the remaining dedicated writers.

Sadly, as Cahalan reports, he’d “grown up,” found happiness with Clarke, his fifth, and final, wife, when his profligate lifestyle caught up with him. His books were selling, he had secured a permanent place as a professor at the University of Arizona, and he and Clarke had two young children. He had faced his mortality when he was wrongly diagnosed with pancreatic cancer several years prior to his death, giving him another six years. However, he developed what he himself called “the old wino’s disease,” technically esophageal varices, that causes undetected internal bleeding. After a valiant fight for a few years, he found himself hospitalized, with only a grim prognosis.

That led to Abbey’s last great act of rebellion: He died on his own terms. A few years earlier he’d made a couple of close friends swear they’d not let him die in a hospital, under the fluorescent lights, tied to tubes and suffocated with the nauseating smell of antiseptic. So, when Cactus Ed reached the end, hospitalized against his will, they appeared to free him. In memorable style, they took him to the small writing cabin behind his home, where he quietly passed in the company of his family, his five children, and friends. They then took his body out into the desert, to an unknown spot, and illegally buried him. They piled rocks on top to deter coyotes, and placed a large boulder bearing the inscription he wanted. “Edward Paul Abbey, 1927-1989, No Comment.”

In the following days, people were shocked to read of his death. He’d been active until the end; only a few close friends knew he was ill. Abbey wanted no funeral, only a wake, where he wanted poetry, music, drinking, love-making and a big party. There were two such events, one near Taos, and another at his beloved Arches.

Thirty years after his death, Abbey’s Desert Solitaire remains as ever. Professors assign him and writers reference his work. Now that many of our parklands are under the growing threat from the current administration that sees natural resources to be far more important than either natural beauty, sacred lands or indigenous wildlife, one can only imagine what Abbey would do.

“He was the Mark Twain of the American desert; he was bad behavior and big-hearted ideas,” wrote conservationist and author Terry Tempest Williams. As his pal Jack Loeffler said, “He was a great friend, not a great role model.”

Nano Riley is the author of Florida Farmworkers in the 21st Century and an instruction for Eckerd College's Osher Lifelong Learning Institute.