Adventures do occur, but not punctually.

One time in high school, about a hundred years ago, I was working on a book report on E. M. Forster’s Passage to India, and read a brief bio that said “As a young man, Forster decided to devote his life to writing.” I immediately thought something like, “Well, there’s an idea — writing would be a great adventure — but just how does one go about it?” I had enjoyed writing early on. For about a year, as a nine-year-old, I wrote The East 32nd Street Eaglet, a one-or two-page newspaper modeled on The Brooklyn Eagle which arrived daily on our stoop in Flatbush, where my father read it from start to finish. Maybe I could be a journalist; after all, Walt Whitman was the Eagle’s editor about a hundred years before my Eaglet. Later on I found out that Forster had received an inheritance of £8,000, very large in those days, from a paternal aunt. I had many aunts, whom I was very fond of, but as I watched them play pinochle for pocket change, I saw that wasn’t an option in my case. How could I support my addiction to poetry, an addiction so secret I didn’t realize it myself? Like the licorice sticks I bought for a penny from our corner store, it was just something I did.

A short stint as a writer for The Citizen of Morris Country in New Jersey, while I was teaching at Mountain Lakes High School, decided me that neither newspaper writing nor high school teaching, though both helpful, would enable me to write the poems that were piling up in my notebooks, unfortunately (well, perhaps fortunately) hurriedly scribbled in my indecipherable handwriting.

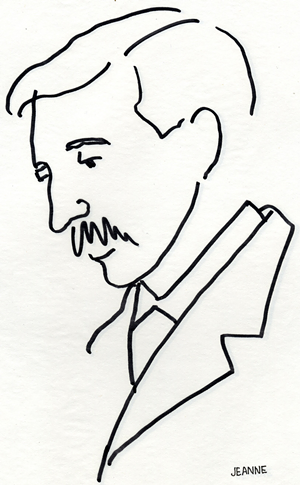

The major adventure toward arriving at a writer’s life came in 1960, when Jeanne and I dropped all pretense of being sensible people, rented a U-Haul, and headed out to Ann Arbor for graduate school at the U. of Michigan. We weren’t teenagers; we had two small children, and I was 28, not at all precocious. But I can still feel that excitement as we drove through the night to save money, knowing everything would be different. A life full of books and art, surrounded by people who couldn’t live without both. Could I pass the tests? Would the editors take our drawings and poems? We started sending our work out into the world.

I’m thinking about Forster because he was born on January 1st, 1879, and reading his books and bios first made me think that a writer’s life should include travel and intrigue more adventurous than shooting bears and antelopes like Hemingway.

Oddly, we’re less hopeful than we were in 1960. We didn’t know what awaited us but the country felt solid. 2019, on the other hand, looks slippery. Things are swerving apart, and it seems this isn’t the time when we’ll come together. Americans want to be friends, with our allies, with our competitors, with our environment, with our leaders, with our neighbors, with those in need. But — as at the end of A Passage to India when Dr. Aziz and Prof. Fielding are riding on horseback toward Mau — it won’t happen today. Not yet, not in our lifetime. I feel we — as older writers and teachers — have let the country down. But here at Christmas, looking at our bright, good-hearted, talented and multi-colored grandchildren, I can’t help thinking, Well, it’s OK. They can do it.

“Why can’t we be friends now?” said the other, holding him affectionately. “It’s what I want. It’s what you want.” But the horses didn’t want it — they swerved apart: the earth didn’t want it, sending up rocks through which riders must pass single file; the temple, the tank, the jail, the palace, the birds, the carrion, the Guest House, that came into view as they emerged from the gap and saw Mau beneath: they didn’t want it, they said in their hundred voices “No, not yet,” and the sky said “No, not there.”

—both quotes from A Passage to India by E.M. Forster (Harcourt, Brace and Co., NYC)