American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell

Tampa Museum of Art, 120 W Gasparilla Plaza, Tampa, through May 31. 813-274-8130, tampamuseum.org

At the start of her 2013 biography of Norman Rockwell, Deborah Solomon sums up the artist’s complicated status as one of America’s best-known, most beloved and most disdained of 20th-century art makers: “The scathing condescension directed at Rockwell during his lifetime eventually made him a prime candidate for revisionist therapy, which is to say, an art-world hug,” she quips.

American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell, an exhibition at the Tampa Museum of Art, puts one in the mood for such an embrace. Organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Mass., the show comprises more than 100 works by Rockwell, including the complete set of 323 covers he produced for The Saturday Evening Post between 1916 and 1963, original paintings, archival documents and photographs. Whether you admire Rockwell’s draftsmanship or squirm at his sentimentality, you can’t help but walk away from the exhibition — like Solomon’s biography, American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell — with respect for an artist whose prodigious ability to render the natural world in paint was accompanied by a fair share of self-doubt and self-effacement, hard work and an evolving desire to promote social good.

Some viewers may be surprised to learn, in particular, that Rockwell devoted the late years of his career (before his death in 1978) to addressing issues of civil rights and racial equality in paintings and illustrations. On Friday, the Heard ’Em Say Youth Arts Collective, a local group of teen poets led by spoken word artist Walter “Wally B.” Jennings, will perform their original responses to these and other Rockwell works at GASP!, TMA and CL’s annual fringe festival (see story next page).

The Post was the vehicle by which Rockwell became known to Americans, but it was not his first gig. One thing the exhibition does well is show how Rockwell’s earlier work, especially for Boys’ Life, the official Boy Scouts magazine, led to what later became his signature style: richly narrative, hyper-detailed and slyly comical illustrations of people in action, often doing something quintessentially American (playing baseball, mooning over photographs of celebrities) and modern.

When Rockwell became a regular contributor to the Post, his view of America through youth and family scenes marked a radical departure from the magazine’s typical cover art of portraits of beautiful women. (Depicting women who actually did something would become a Rockwellian innovation.) His first cover is a choice example. In it a boy wearing a formal suit pushes his baby sister in a stroller past two other boys, dressed for an afternoon of sport, whose facial expressions say, “So long, sucker!” While eliciting a laugh, the image created a pause for reflection on what it meant to be a boy, then as now, and the contest between responsibility and pleasure in life at all stages.

As a dozen or more examples in the exhibition demonstrate, Rockwell painted his compositions in oil on canvas first, larger than the magazine cover size, so the images would reproduce well when reduced. Seeing evidence of this process drives home that Rockwell’s work was not complete when a canvas was simply finished, but only when it had taken on a second life as a picture circulated into 6 million U.S. homes at a rate of a nickel per copy. The timeline of Post covers in the exhibition offers up a parade of his most popular images, from Dickensian Santa Clauses and playful children to G.I. homecomings and Rosie the Riveter (not a character invented by Rockwell, but one of his most enduring portrayals).

Rockwell’s affiliation with the Post ended in 1963 when the magazine’s management and its approach to cover art changed. At age 69, he was thinking about other projects he wanted to pursue, including a painting commemorating President John F. Kennedy’s creation of the Peace Corps that Rockwell completed in 1966. The period coincided with a shift in his politics, which seemed to crystallize with Kennedy’s assassination, toward promoting civil rights through his art. The last segment of the exhibition explores this theme powerfully — with a tragic sense of relevance born of our own post-Trayvon, post-Ferguson context.

"Murder in Mississippi" invokes the killings of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, three civil rights workers who were rounded up and shot in close range by KKK members and local law enforcement during the Freedom Summer campaign of 1964. The exhibition offers an extended presentation of Rockwell’s development of the work, including an initial sketch (the image that was ultimately printed as an illustration in Look magazine in 1965), process photographs of models, related articles collected by Rockwell, and the final painting, as well as letters from readers responding to the published image. (In correspondence with his editor, Rockwell frets that he hasn’t got the painting just right and laments not being more like Ben Shahn, the renowned social realist painter.) To create the gripping tableau, which depicts a moment when two of the men have been shot and the third waits to be slain, Rockwell used an uncharacteristically painterly approach, abstracting the sepia-colored figures slightly with the effect that they resonate as much as symbols of humanity as individual men.

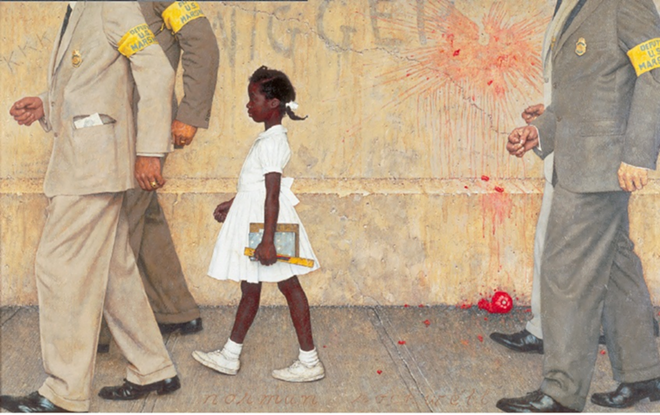

Holding its own in the same gallery is Rockwell’s portrait of a lone girl, Ruby Bridges. In 1960, 6-year-old Bridges became the first black child to attend a white elementary school in New Orleans and the South. In his famed painting, titled The Problem We All Live With, which appeared as a two-page illustration in Look in 1964, Rockwell deploys all of his Saturday Evening Post tricks to different ends. The painted Ruby (like the one captured in news photographs of the time, but different) brims with personality as she strides toward school, head high in a starched white dress and clutching supplies at her side, the slight curve of her lips hinting at a smile. In an earlier kind of Rockwell scene, she might have illustrated an idyllic, everyday American childhood; in this one, U.S. Marshals escort her past a wall defaced with a racial epithet and a thrown tomato (Bridges’ everyday reality, but far from idyllic).

For all of the detail and narrative packed into the picture, one of the most moving things about it is the tone and luminosity of Ruby’s purple-brown skin, which Rockwell has masterfully rendered as velvety soft and beautiful in a wordless rebuke to the nasty scene and to discrimination. To convey the vulnerability and strength of a child juxtaposed with the injustice of prejudice through the materiality of paint is something more than illustration — it’s art.