He wanted to be like Jesus

but he was rich and married besides

empediments to sainthood or even

telling the truth...

(from 'Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana')

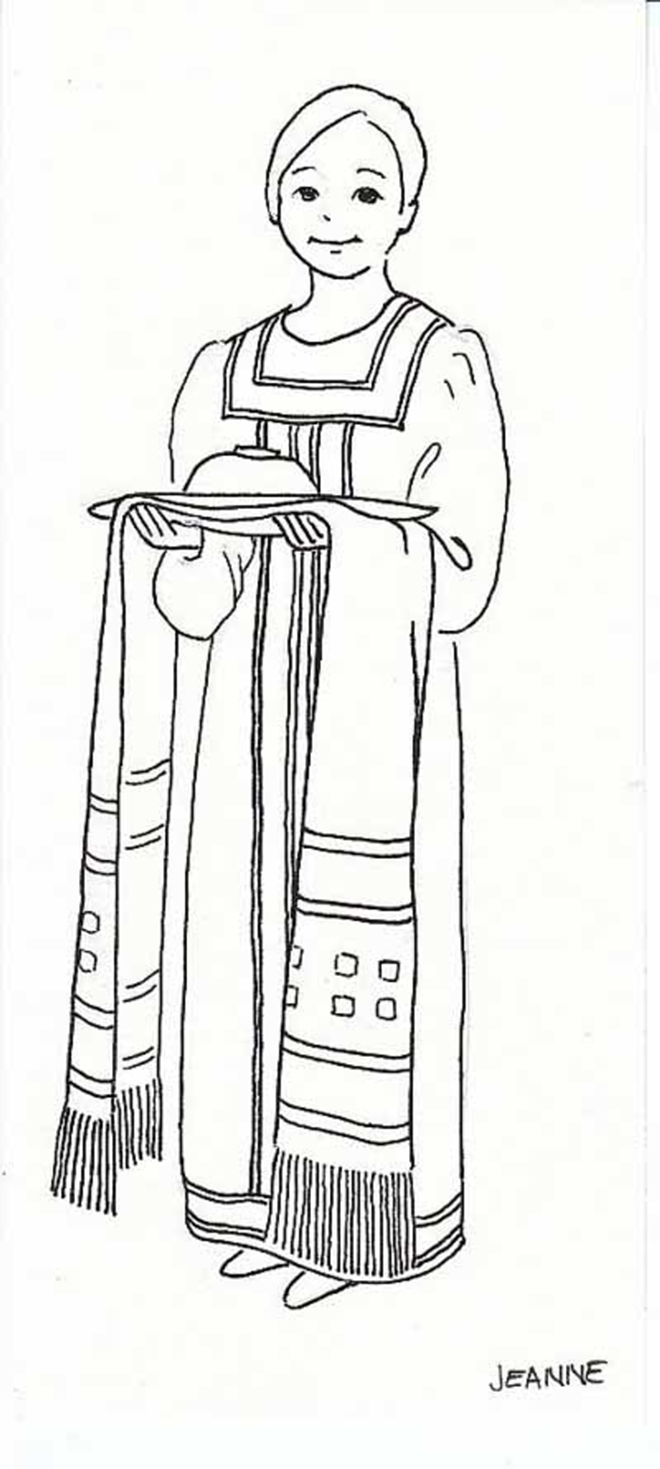

In the summer of 2003, Jeanne and I took a cruise along the Neva and Volga Rivers, between St. Petersburg and Moscow, celebrating the symmetrical birthdays of our St. Pete (100th) and Russia's (300th). In St. Petersburg, I recited some poems, with translator and poet Ilya Foniakov, on a midnight poetry call-in radio program. What a country! I thought, when the calls started pouring in, many of them seemingly sober. (The only Russian I know is Nastrovya!, said before downing a vodka.)

While in St. Petersburg, we thought of Fyodor Dostoevksy, brooding over his desk in a small apartment (now a museum) near the Vladimirskaya metro station. When I was young, I loved the great Russian 19th-century novelists — Gogol, Lermontov, Tolstoy, Turgenev — but Dostoevsky was my favorite. I am a sick man. I am a spiteful man. I am an unpleasant man. I think my liver is diseased. However, I don't know beans about my disease... This is the unforgettable beginning of his Notes from Underground, and its jaundiced inward-turned voice appeals to young people questioning the societies they're entering.

But as I grew older, the wide-angled realism of Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) appealed to me more and more, and when we cast off from St. Petersburg and meandered along the great rivers toward Moscow, getting a feel for Russia's vast expanse and the friendliness of the villagers we met along the way — in Svirstroy, Goritsy, Yaroslavl — I got the crazy idea that I wanted to reread Tolstoy's massive masterpiece, War and Peace.

I'll do it, I said to myself. Nastrovya.

Of course, back home, when I almost broke my wrist pulling out my old volume, I put the project off. 1200-plus pages! So I repressed my vow until last year, when I read that Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky had published a brilliant new translation. Impulsively, I bought it ($37!), and it squatted on its shelf, glaring at me like a Russian bear, for another year. Three months ago I started reading it. Right away I learned I couldn't read while lying on the couch; the book hurt my chest, and I couldn't hold it up. So I sat at my desk, feeling like a schoolboy again.

War and Peace, written steadily for five years on Tolstoy's beloved estate, Yasnaya Polyana, "under the best conditions of life," takes place during the Napoleonic Wars (1805-1812). Over 500 characters spill from its churning pages (many with multiple nicknames: Natasha, Natalya, Natalie), and dozens of them grab you by the lapels like the Ancient Mariner and say, Listen to my story!

When I first read the book I identified with the lean and handsome soldier, Prince Andrei; and one of the first changes that surprised me was that this time I identified with the chubby, awkward, idealistic pacifist Pierre. I don't think it was the translation. Tolstoy's depiction of the bloody uselessness and stupidity of war is gripping, upsetting, and — another change — completely contemporary. This "stupidity" doesn't preclude scenes of extraordinary heroism and selflessness, heartbreaking to read, and to contemplate on Veterans Day November 11. Soldiers coming home from Iraq and Afghanistan, describing scenes of incomprehensible confusion, bravery and cruelty are prefigured in these pages at the battle of Borodino.

And the leaders, too, are as clueless at Borodino as Rummy, Cheney and the rest of that gung-ho group was in ours. (Tolstoy anticipated today's novelists by mixing in historical figures, like Napoleon and Alexander I, with his fictional ones.)

What emerges most powerfully in War and Peace is Tolstoy's love of family life and the strength of the Russian peasantry. Despite terrible setbacks, the staying power of the "good" people is enormous. As I stared at the screaming crowds at our "town hall" meetings, or watched the replays of South Carolina's Joe Wilson yelling "You lie!" at President Obama, I put down War and Peace feeling better, with more faith in the intrinsic sense and virtue of our own basically commonsensical citizens. We will outlast this disgrace.

War and Peace is, in the end, Tolstoy's hymn to the dignity and strength of ordinary people. The size of the book mirrors the largeness of the story, and the large hearts of its central characters. As soon as you retire, pick it up. And use both hands.

...'and why should she marry?' he thought

moving toward the quivering page and us...

The lines framing this essay are from Peter Meinke's poem "Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana" (in his book, Scars). He'll be reading from his latest book, Lines from Neuchâtel, on Thursday Nov. 12, at Lewis House, ASPEC, Eckerd College.