Last year, after Dade County and several South Florida municipalities passed ordinances banning sex offenders from living within 2,500 feet of any place where children congregate, Miami New Times discovered a growing population of sex offenders living under Miami's Julia Tuttle Causeway. Turns out, probation officers were taking the men there because it was the only place in the county where they could live under the new ordinances.

Is society really safer by forcing sex offenders to live under a bridge?

Those ordinances are having another effect, too. Sex offenders are migrating to counties that have less-stringent residency restrictions. Hillsborough County is one of those counties. (The sex offender I interviewed is from Ft. Lauderdale.)

One Florida state senator thinks he has a solution. After visiting the sex offenders under the Miami bridge, Sen. David Aronberg of Greenacres introduced a bill that would make a uniform state law that prevents sex offenders from living within 1,500 feet from places children frequent and expand Hillsborough County's anti-lingering law (that prevents sex offenders from loitering within 300 feet of children) statewide. The proposed law would also require more sex offenders to wear electronic monitoring devices. The law's purpose is to prevent ever-expanding residency restrictions and hopefully drastically cut the number of sex offenders who become homeless or go "underground" to avoid local ordinances.

"I feel this problem jeopardizes public safety," says Aronberg. "This is not about being hard or soft on sex offenders, it's about public safety."

Aronberg says "multiple" local elected officials support his bill.

"Because of politics, local government leaders feel pressure to enact these laws and they can't reverse them when they realize the danger to public safety," he says.

This might not be the ultimate solution — 1,500 feet can still be a barrier to housing in high-density areas — but it could cut down on the amount of homeless sex offenders and those migrating to unsuspecting communities. And I don't think anyone can argue with increased monitoring. Even Bill Fuery, the sexual predator I interviewed, has no problem with it.

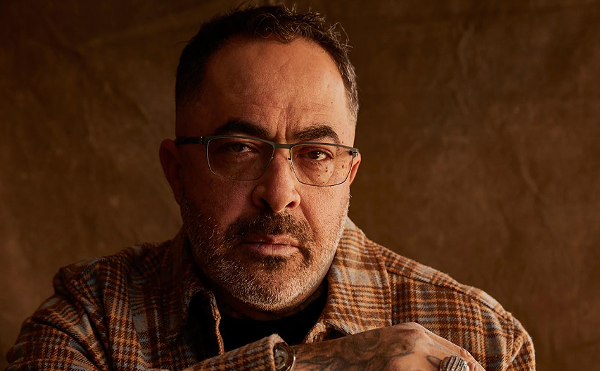

"I think society deserves the accountability they want," Fuery said. "I have to be tracked for the rest of my life. But my victim has to live with what happened. I think I got the better end of the deal.â€

Fuery acknowledged this is a tough issue. He’s not blaming the residents across the street, but he wishes they could meet and talk about their fears.

“There’s no easy solution,†he said. “But people are not looking for answers, they’re looking for vindictiveness.â€

My question to readers: Is that true? Are we letting our disgust for sex offenders cloud our judgement on the best way to deal with them? And do you support Aronberg's bill?