With its no-curbside-recycling and three-decade legacy of secret sewage dumps in the rearview mirror of its theoretical Prius, St. Petersburg’s full steam ahead on smarter environmental choices. Although, given the nature of the latest announcement from City Hall, perhaps the “steam” cliché is misguided.

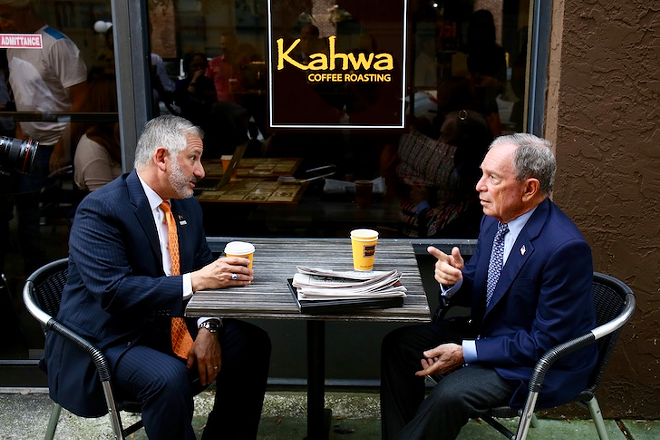

Enter Michael Bloomberg, the ardent let’s-stop-poisoning-the-planet enthusiast who last week told a small crowd in St. Pete he’d come to town to talk about “an urgent challenge facing St. Petersburg and the whole world” and that mayors across the country saw how “their constituents are already feeling the effect [and people] expect city hall to take some action.

“I’m probably the last New Yorker to show up in Florida this winter,” Bloomberg told the somewhat sweaty crowd gathered at Albert Whitted Park on Jan. 3. But he wasn’t there to lunch at Paul’s Landing or take in the white pelicans in the water near Straub Park; instead, he announced St. Petersburg’s acceptance into Bloomberg Philanthropies’ American Cities Climate Challenge.

While the crowd gathered at Whitted reacted with cheers and applause and only two only tangentially related questions from the reporters assembled (Was this part of a strategy in a yet-to-be-announced presidential run? Did Bloomberg know about the city’s wastewater scandal?), this award takes some unpacking to understand, because it doesn’t mean Michael Bloomberg intends to throw money at the city to reduce the size of St. Petersburg’s carbon footprint. Nevertheless, the award should amount to changes in St. Petersburg’s consumption.

What is the American Cities Climate Challenge?

According to the Challenge website, “in nearly every major American city, buildings and transportation consume more energy and are responsible for more carbon pollution than any other sector, totaling 80% of citywide emissions.” That’s why each city accepted into the challenge had to prove it had a plan that could reduce those emissions. The Challenge only accepted applications from the most populous 100 cities, and only cities still committed to honoring the Paris Agreement could apply.

To that end, the 25 cities — five remain unannounced at press time — in the Challenge get their plans for near-term carbon reduction accelerated. The Challenge lasts two years, and during that time the city gets access to world experts who can help each city make its carbon reduction goals a reality. Each city will focus on reducing its carbon emissions in buildings and transportation, although each city’s plan, Bloomberg told the crowd, will differ, adding that Sharon Wright, the city’s Sustainability and Resiliency Director, had crafted St. Petersburg’s.

Over the next two years, St. Petersburg will have a climate advisor — paid for by Bloomberg Philanthropies —from the National Resources Defense Council; the city will also have access to experts across the world who will help make city facilities as energy efficient as possible (the goal, Wright tells us, is to “ultimately include renewable energy” in all city buildings).

While the city must spend its own money to make the physical changes — for example, to make most city vehicles part of a “green fleet” of electric vehicles — the Challenge gives each city access to experts who can offer advice on how to make successful changes.

Think of it as St. Petersburg having a carbon-reduction sherpa.

So St. Pete’s going to do... what, exactly?

Wright has outlined 20 action items to reduce St. Petersburg’s carbon footprint. One that features bigly plays off the mayor’s favorite saying, “the sun shines here”: solar power. St. Pete’s already installed more than one megawatt of solar energy in single family homes, but the Challenge will help them bring solar to more people.

“We have some ideas for scaling that up and expanding it,” Wright said. “We’d like to get to multi-family and business. Now, maybe we can go to a large employer and offer it to their employees — we’d like to expand it to include EV and battery storage and maybe be able to expand to businesses and multi-families.”

Wright also wants to see the city switch to electric vehicles. She says it’s even possible for first responder and public safety vehicles — Hyattsville, MD has EV police cars, and Zero Motorcycles makes a police motorcycle with top speeds of 102.

She also wants to implement a “private sector challenge” whereby people and large employers voluntarily share their energy bills and agree to energy audit to find ways they can be more efficient. And yes, that does sound a lot like what Duke Energy will do for its customers, but with one difference: Duke Energy doesn’t share data, so St. Pete can’t access it to track energy use and see where most people need the most help. Fun fact: Denver requires all private buildings to track and report energy use, and the city helps facilities it sees having problems.

St. Pete would also like to help low-income families make changes. Reducing one’s carbon footprint, for the poorest families, is a luxury — feeding a family and keeping a roof over their heads trumps installing solar panels. Wright wants to see the city help find mission-based investors and grants as part of the Solar and Energy Loan Fund. SELF helps fund carbon-reducing improvements for anyone, regardless of credit score. SELF functions as a Community Development Financial Institutions Fund, and that means it must make sure 60 percent of the loans its services go to people with low incomes.

And here’s what Wright calls the “moon shot” for St. Petersburg: She wants a community solar farm (members split the cost of building it and everyone gets solar power and lower power bills) in a low-income area. No such farm exists, but, as part of the Challenge, St Petersburg could have a pilot program by December 2020.

How much is this costing me as a taxpayer?

Not a cent. The changes to the city’s infrastructure may or may not impact the millage rate, but participating in the American Cities Climate Challenge costs St. Petersburg nothing.

“I think it’s unrealistic to think we’re going to [eliminate fossil fuels] overnight,” Bloomberg said last week, but added how mayors see the front line impacts of climate change, citing the example of constituents who have to bring their kids to the ER because of asthma attacks. “That’s something that mayors understand even if the White House clearly does not.”

Contact Cathy Salustri here and don't forget to sign up for Creative Loafing's weekly Do This newsletter.