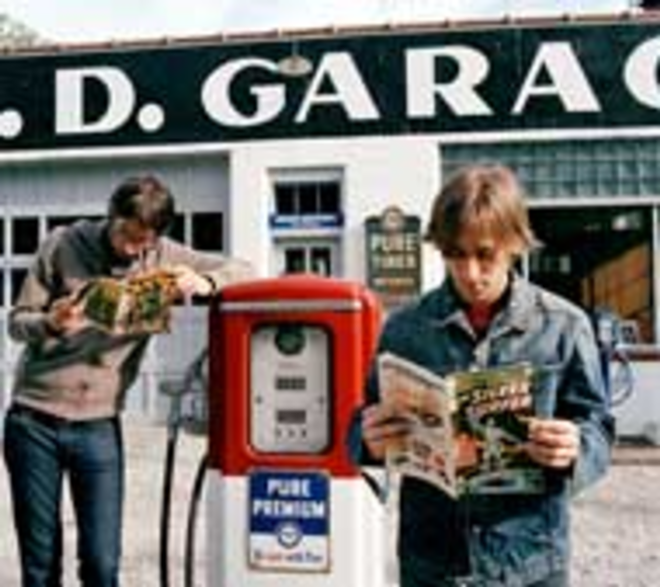

"Our first show was just horrifying," says Dan Auerbach, singer, guitarist and songwriter for the Akron, Ohio blues-rock duo The Black Keys. "Not that we were bad; we were terrified. We played the songs at triple speed and went backstage and sat down out of breath."While the Black Keys' have been a critically lauded cult act for quite awhile, with three albums of rough-and-tumble trash blues under their belt, the tandem's first gig was just in 2002. Auerbach and drummer Patrick Carney, who formed a musical partnership a decade ago while in their mid teens, scrupulously avoided live performance. "We were always musicians first, not entertainers," Auerbach says by phone.

The partners started recording Auerbach's original tunes in Carney's basement - just for themselves. Both dropped out of college and upon their return home put together a five-song demo. "We sent it out to 12 indie labels we thought might be interested," Auerbach explains. "[California's] Alive Records said if we sent them 10 finished songs, they'd put out an album. All the others wanted to see us play first…"

Auerbach pauses briefly: "We went with Alive."

The Black Keys' 2002 debut, The Big Come Up, generated enough buzz to make one thing quite clear: The stage-shy Ohioans would have to tour. The Black Keys debuted at the Beachland Tavern in Cleveland in front of a small crowd. They made 10 bucks. But the owners liked the duo, despite their stage fright, and invited them back.

It's only gotten better since. After a first tour that Auerbach describes as "disastrous," The Black Keys landed a solid booking agent and have significantly upgraded their road status. And their knees no longer quake when they hit the boards. "We don't need to be on stage," he says. "I'm sure James Brown has a need. We don't. Being in front of people is not so important to us. That said, we have a great time when we play live, and if the audience gets into it, it makes us better. It's dependent on give-and-take. It's definitely an interactive game."

While The Black Keys continue to tour, they're far happier in the studio, perhaps no more than last year for the recording of Rubber Factory (Fat Possum/Epitaph), which landed on a slew of the year's best-of polls and lists (including this scribe's).

Having outgrown Carney's basement, the duo came across a "For Rent" sign on an old General Tire factory in Akron. The first floor was filled with cavernous storage spaces, but upstairs there were smaller rooms that had been offices and laboratories. The guys leased a room in the deserted R&D section, bought a bunch of used analog gear and ran cables around the halls to set it up. It took a couple of months.

Using recycled tape from Fat Possum studios outside Oxford, Miss. (the label is home to R.L. Burnside, T-Model Ford and the late Junior Kimbrough), the duo began cutting tracks with a vengeance. "For the first couple weeks, it was seven days a week all day long, even though we both have our own places," Auerbach says. "There was a little diner around the corner where we'd go eat. The waitress knew what we wanted, and when we walked in they started making our food."

The hectic pace then tapered off, and the partners indulged in extensive tweaking and overdubbing. They even executed an impeccable back-masked solo on the creeping "Desperate Man" - in one take, of which Auerbach is quite proud.

The recording process gave Rubber Factory a decidedly visceral and sooty sonic presence that is by no means lo-fi. It's a perfect fit for music that evokes darkened back roads, dangerous characters and sneaky sex. The music bulges with barbed riffs and chunky chords, its fullness resulting from Auerbach's five-finger picking style, where his thumb plucks out bass notes.

Carney's energetically unrefined drumming gives the sound a slapdash drive. Auerbach's menacing moan, a voice that's world-weary beyond its years, lends a dark soulfulness. The songs are further punched up by his pointed guitar solos, be they greasy chords, wah-wah workouts or fuzzy throwdowns. In all, The Black Keys' alchemy does not stir in anything particularly new, but there's something fresh about how it all comes together.

It is, all told, an exquisite amalgam of their influences. Auerbach, the cousin of the late, influential punk guitarist Robert Quine, lived down the street from Carney, the nephew of long-time Tom Waits saxophonist Ralph Carney. Auerbach's father fed him a steady diet of vintage blues by Son House, Robert Johnson, Billie Holiday et al. His mother's side of the family hailed from Georgia, and many of them played bluegrass. All of it "made me want to pick up the guitar," he says.

The two would see each other around the neighborhood, but because they were in different grades, didn't hang out together. One day, "someone introduced us as two people who played music," Auerbach recounts. A collaboration was born. Carney was into the Sea and Cake and other arty post-rock. Both liked hip-hop and soul. "I was listening to a lot of solo electric blues by Lightning Hopkins, the one-man bands, the groups with two guitars and drums, but no bass," Auerbach explains. "When we got together, we just never felt the need [to expand the lineup]."

Although they overdubbed freely in the studio, The Black Keys refuse to augment their dual-instrument assault with any computer chicanery. "When we're live, it's just the two of us," Auerbach asserts. "No effects, no samples, just drums, guitar and vocals. So the songs have to change a little bit to work for the live set."

Carney, the more flip of the two Keys, has said that one of the secrets of making the two-man band format work is "you turn everything up loud … real loud."