It’s a place where left-leaning coastal urbanites push for progressive policies while rural and exurban populations push back against what they see as a too-rapidly evolving society that is leaving them behind.

And, like the rest of the country, the population is deeply polarized, which we can see playing out in comments sections, social media posts and city council and county commission chambers everywhere.

That’s why, despite it being the year 2017, it’s so fitting that a debate is raging over Memoria in Aeterna, the controversial Confederate Army monument that stands outside a Hillsborough County courthouse annex in downtown Tampa.

The obelisk is a tribute to soldiers who fought for the Confederacy. Chief among the reasons the South seceded was to retain slavery (per the Articles of Confederation). The South lost. In 1911, 50 years after the start of that war, the statue was dedicated with great fanfare. The state attorney who delivered the keynote that day had some pretty awful things to say about minorities (even if he apparently condemned slavery in his next breath).

Against the wishes of County Commissioner Les Miller, who is African-American and sees the monument as a symbol of ingrained racism, the Hillsborough Board of County Commissioners voted 4-3 for the thing to stay put. They’re also opting to pay someone to chisel some kind of bas-relief monument to diversity on the wall behind it and to put some money toward anti-racism education programs (whatever that means).

Despite the compromise, emotions are running high on both sides of the issue. I explain my position below; CL’s A&E Editor Cathy Salustri follows with a counter-argument.

Bradshaw: It ought to go somewhere else

We can’t begin to know what’s in someone else’s heart. That’s why I would never accuse someone who supports keeping this statue in place of being racist. But I can posit that leaving the monument where it is — on public property in busy downtown Tampa, where people go to renew their passports, obtain marriage licenses and the like — is at the very least insensitive to the descendants of slaves.

Prior to the Civil War, the nation, especially the South, was a brutal dystopian regime that thrived off the enslavement of millions. (Arguments about Africans selling each other into slavery or Lincoln initially not interfering with it, probably out of political expediency, are red herrings and don’t justify keeping the monument where it is.)

The monument went up at a time when the sentiments that inspired Jim Crow were raging and southern whites made no secret of their racism — and some expressed it in violence.

For Commissioner Les Miller, who proposed the monument’s removal, passing the statue each day as a student in the 1970s was a constant reminder of a vile social order that placed little to no value on an entire group of human beings — a mindset that stains many of our institutions to this day.

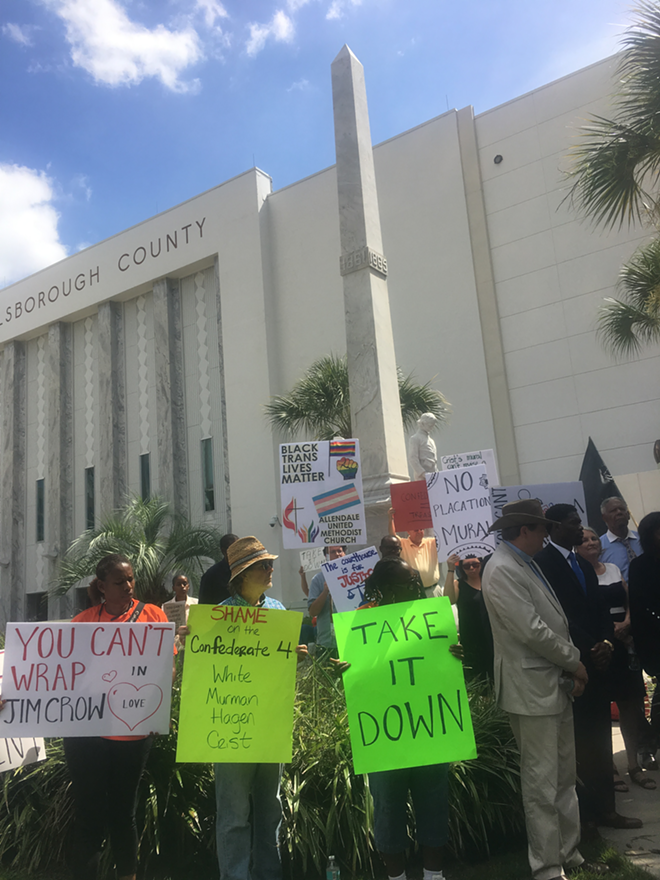

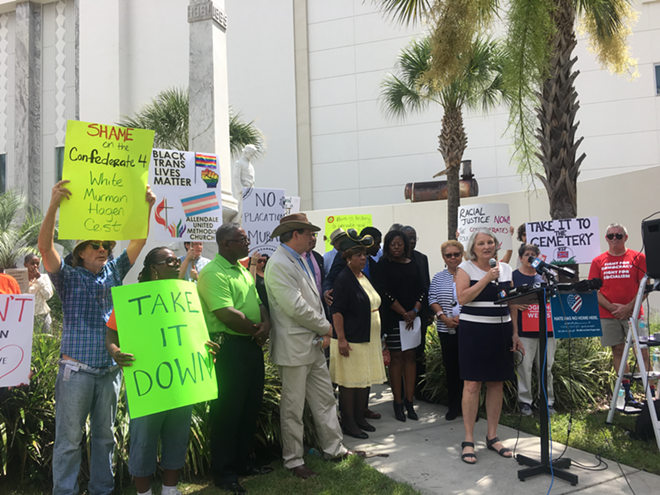

“When we look around this county and this city, what we see is the persistence of racism [in] every one of our institutions: employment, schools, housing, healthcare, the courthouse, the county jail,” said Rev. Russell Meyer during a press conference beneath the monument the Tuesday after the commission vote. “The persistence of clear racial disparity, easily mapped by any measure of statistical information you can find online, persists to this day in this county. And this statue represents the history and the transmission of that disparity. The removal of this monument to a more befitting place is the first step in saying we’re going to be intentional about righting the historical wrong that has been the long history of Tampa.”

That a monument honoring the Confederacy stands at a public institution doesn’t do much for the expectation that everyone who passes through those doors will receive equal treatment under the law.

“That may have been good when it was put up, but this ain’t your daddy’s county,” said Rev. James Golden Esq. at the Tuesday press conference. “This ain’t your granddaddy’s town anymore. As it has been pointed out, there’s too much progress that has been made. There’s been too many strides that have been taken to bring us here to this point. And we will not go away and we will not stop. To the four of you, one of you must change not just your mind, but you’ve got to change your heart.”

It’s noteworthy that the only Republican County Commissioner to vote in favor of removing the statue, Al Higginbotham, is also the only Republican on the dais who is not going to be running for re-election; he’s retiring, and doesn’t have to worry about what constituents in the reddest parts of the county think of him. He appeared to speak from the heart during the hearing about how, as a person with a physical disability, he understands on some level what it’s like to be treated differently. Commissioner Sandy Murman, a Republican who voted to keep the statue in place, expressed similar sentiments about experiencing sexism — but it didn’t change her thinking.Activists also bring up a good point about the economics of keeping Jim Crow relics on the grounds of highly visible institutions rather than, say, a veterans’ cemetery or a museum. Given that city, county and state officials are aggressively seeking to redefine Tampa as a bustling, cosmopolitan hub (lackluster transportation solutions aside), sporting a monument many see as racist (or at least vestigial of a time when being racist was OK) doesn’t seem like a smart way to attract visitors or businesses to the area.

Relocating the monument — which is what’s been done in cities like Orlando, Gainesville and New Orleans — to a more appropriate venue probably won’t soothe the bitter divisions within the community that have been stoked over the past two years. In fact, it may cause outrage along Hillsborough’s rural and exurban perimeter. But it will signal the desire among public officials to make Hillsborough County a better place, one where everyone can expect not just equal treatment, but to be welcomed regardless of background.

Salustri: Here’s why it should stay

Memoria in Aeterna means “everlasting remembrance.”

That’s the name of the statue, created in 1911 and moved to the Hillsborough County Courthouse in 1952.

“It brings up a dark side of our history,” Al Higginbotham said in defense of tearing down the statue.

Which is exactly why it should stay put.

“Racism is alive and well. Even as we sit in these chambers it is felt around the world. I do not need to be intimidated or reminded of that every time I go to the courthouse and do business,” said Bishop Michelle B. Patty, making the argument for demolition.

That, too, is exactly why it should stay put.

“We don’t want to look like a Southern hick town,” Charles Hearns said.

Thing is, we don’t need a statue to remind us of that. In a red county of rebel flags and “Forget, Hell” mudflaps, it’s going to take more than tearing down a statue for it to look progressive.

And tearing down the statue will not end racism; it will allow it to continue.

Let me explain. At a recent meeting about the statue, someone held up a sign that compared retaining the statue to Berlin erecting one of Hitler (theoretical, of course, as Germans have a “pathological” fear of patriotism after Hitler).

But a statue of unnamed veterans isn’t a statue of Hitler, or Jefferson Davis. It’s not waving a flag.

What’s on this statue, anyway?

Two soldiers, one facing north and one facing south. The northern-facing soldier may be facing the invading army (the date on the north side is 1861); the southern-facing one is returning home a loser after war, his uniform in tatters (this side bears an 1865 date). There’s also a poem, written by Sister Esther Carlotta, which makes it clear:

The South lost the war.

As Americans, we’re winners. We’re the greatest nation ever. American exceptionalism is alive and well. We’ve never lost a war. Well, if you don’t count Vietnam.

Or the Confederates who lost the Civil War.

In The Burden of Southern History, C. Vann Woodward, a noted equality supporter influenced by liberal southerners as well as African-American scholars Langston Hughes and W. E.B. DeBois, argued “the Southern heritage, the collective experience of the Southern people, may some day serve a useful counterbalance to the national experience and the national myth.”

Woodward also wrote that because southerners remember what it means to have lost a war, the South has more in common with “the ironic and tragic experience of other nations” than any other part of America.

The Burden of Southern History, of course, makes no suggestions as to what Hillsborough County should do with its statue. Please, though, consider this famous quote from Edmund Burke: “Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it.”

The statue should stay. It represents a chapter in our history we must not minimize or erase. We cannot secret away the parts of history of which we are ashamed. Removing a statue won’t erase the modern problems created by slavery and the war the South fought to continue owning black people.

Leave the statue. But don’t “wrap it in love” with another piece of art nearby; instead, contextualize it. Explain this is the one war America has lost. Explain how these two soldiers could have been men who believed in the slave-based economy or 14-year-old boys sent to fight when the South emptied local military academies and sent children to die. Explain that after this war, America was a shambles; that generations later, the black community faces continued problems the white community never will. Explain that after the war, the Union divided the South into five military zones. Explain that some Americans chose money over liberty. Explain how people cloaked their racism with the battle cry of “states’ rights” (something we still hear today from many of our elected leaders). Explain that yes, there is a portion of America that maybe feels like it needs to be made great again because it has known what it means to have lost a war.

Contact Kate Bradshaw at [email protected]. Contact Cathy Salustri at [email protected].