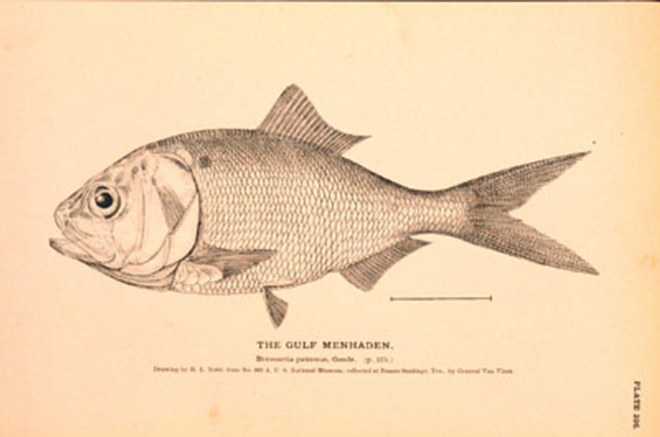

But where did this enormous biomass of menhaden, so crucial to the food chain above it, come from? Just as all those saltwater fish are composed mainly of menhaden, all those billions of tons of menhaden are composed almost entirely of billions of tons of the tiny particles of vegetable matter known as phytoplankton. Eating is just as crucial an ecological mission for menhaden as being eaten.

Eons before humans arrived in North America, menhaden evolved along the low-lying Atlantic and Gulf coasts, where nutrients flood into estuaries, bays and wetlands, stimulating the potentially overwhelming growth of phytoplankton. Although menhaden are the major herbivorous fish of these coasts, they don't chomp on plants. They are filter feeders that live on phytoplankton, which most other aquatic animals are unable to eat. Dense schools of menhaden, sometimes numbering in the hundreds of thousands, pour through these waters, toothless mouths agape, slurping up plankton and detritus like a colossal submarine vacuum cleaner as wide as a city block and as deep as a train tunnel. Each adult fish can filter about four gallons of water a minute. Purging suspended particles that cause turbidity, this filter feeding clarifies the water, allowing sunlight to penetrate and encourage the growth of aquatic plants that release dissolved oxygen and harbor a host of fish and shellfish.

Much of the phytoplankton consumed by menhaden consists of algae. Excess nitrogen can make algae grow out of control, and that's what happens when vast quantities of nitrogen flood into our inshore waters from runoff fed by paved surfaces, roofs, wastewater, overfertilized golf courses and suburban lawns, and industrial poultry and pig farms. This can generate devastating blooms of algae, such as red tide and brown tide, which cause massive fish kills, then sink in thick carpets to the bottom, where they smother plants and shellfish, suck dissolved oxygen from the water, and leave dead zones that expand year by year.

In the natural ecosystem, menhaden cleaned the upper layers while another great filter feeder, the oyster, cleaned the bottom. But as oysters have been driven to near extinction in many Atlantic bays and estuaries by overfishing and pollution, menhaden are left as the only remaining check on deadly phytoplankton explosions. Marine biologist Sara Gottlieb, author of a groundbreaking study on menhaden's filtering capability, compares their role with the human liver's: "Just as your body needs its liver to filter out toxins, ecosystems also need those natural filters." Overfishing menhaden, she says, "is just like removing your liver."

The Narragansett called the fish munnawhatteaug, "that which manures," soon corrupted to "menhaden" by the English colonists. The Abenaki of Maine called them pauhagen, their word for "fertilizer," hence "pogy," still a common name for the fish. This is the fish Squanto may have taught the Pilgrims to plant with their corn.

In the early 19th century, menhaden became an industrial-scale fertilizer for the coastal farmland of New England and the mid-Atlantic, with countless rotting fish spread out over many acres to prepare the land for crops. Groups of farmers often formed small companies — with jaunty names like Coots, Fish Hawks, Eagles, Pedoodles and Water Witches — that owned the boats, huge nets and draught horses necessary to catch and haul tens and even hundreds of thousands of fish at a time.

With industrialization, the demand for lubricants and liquid fuel soared, a demand at first satisfied mainly by whale oil. But after the 1850s, with whales hunted to scarcity, menhaden became America's main source of industrial oil. By the mid-1870s, the production of menhaden oil was 50 percent greater than the production of whale oil. More than 400 sailing ships and steamships hunted menhaden up and down the coast from Maine to the Carolinas, chasing schools sometimes 40 miles long. A single haul of a purse seine would often be filled with fish weighing as much as a blue whale. Almost 100 factories extracted the oil and sold the remaining "scrap" or "guano" as fertilizer for nascent agribusiness. The menhaden reduction industry had become a major component of the U.S. economy.

The reduction fishery reached its zenith during the technological frenzy that possessed the nation in the wake of World War II. The tools of war were directed at the little fish, as leftover naval vessels were converted into menhaden ships guided by spotter planes. Locating the schools no longer depended upon a lookout in the crow's nest of a ship wallowing amid the waves. A spotter plane, canvassing huge areas at high speeds, could quickly spy schools that ships would not have detected. Hall Watters, a former World War II fighter pilot who in 1946 became the first menhaden spotter, recalled how in 1947, flying at 10,000 feet about 15 miles off Cape Hatteras, he spied a school so big that it looked like an island. Another time, Watters spotted a school about "five city blocks in diameter" and "dragging mud in 125 feet of water," that is, solid from the surface all the way down 125 feet to the seabed. Dozens of boats managed to surround and annihilate the entire school. "I couldn't believe they could destroy a school that size," Watters recalled.