Directly across the street at Twiggs and Tampa Streets, workers operated a giant wrecking ball while bulldozers tore the 98-year-old Mass Brothers building to the ground.

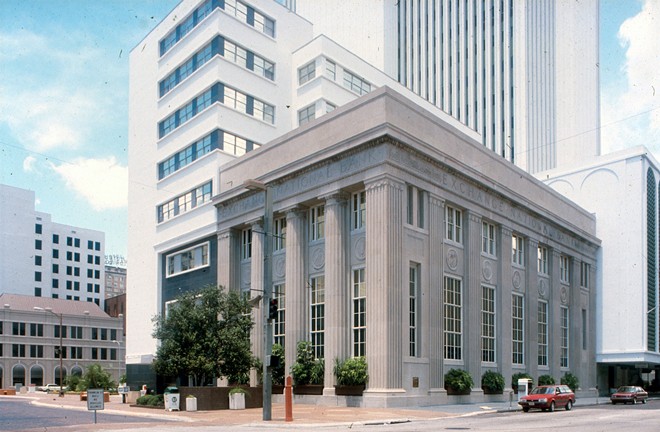

Abe and Isaac Mass founded Maas Brothers in downtown Tampa in 1888. In 1920 they moved into a former bank building on Franklin Street, where they stayed for the next 71 years, growing Maas Brothers into one of the largest department stores in Florida, with a dozen or so locations across the state. But downtown Tampa remained its flagship, a downtown icon until the early 1990s.

But it wasn’t just one historic building in the crosshairs that day. Maas Brothers had expanded haphazardly over the decades, absorbing neighboring buildings as it grew. The portion of the department store facing Twiggs, where I sat sipping my Red Stripe, was originally the Strand Theatre. Built in 1915, 11 years before the Tampa Theatre opened around the corner, Maas Brothers took it over in 1949. As I sat at my café table, bulldozers chewed at the balcony seats as the proscenium of the theater stage buckled.

Today, the site where Mass Brothers and the Strand once stood is a surface parking lot, sucking up space in the near center of downtown for almost two decades. A 32-story condo tower never broke ground.

Last month, 2006 came rushing back as I watched both the Tarr Furniture Company building (1912) and the original Tampa Tribune building (1895)—located across from the Mass Brothers store—get pounded into dust.

In those 17 years, the destruction in downtown Tampa has continued nearly unabated: In 2007, a fire ripped through the 1926 Albany Hotel at 1100 N Franklin. The fire leapt south, consuming another vacant building at Tyler and Franklin. The “Grant Block” at Cass and Franklin—home to Grant’s Department Store since 1920—was demolished in 2015, it’s home to the 915 Apartments now. The entire 700 block of Florida Avenue—a commercial strip dating back to at least WWI and home to the original Hub bar—was demolished last year. Meanwhile the Kress Block sits empty, just as it has for the past 30 years or more.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

There are few protections in place in downtown Tampa that would have saved the Tarr and Tribune buildings. It’s not even a National Register Historic District, one of the least-restrictive covenants available for historic resources. Downtown Tampa has no overlay district to guide design standards, and the existing 30-day demolition review for buildings 50 years or older is a narrow window in which to effectively forestall a potential demolition.

Across the Bay, St. Pete’s city codes help to mitigate the loss of historic resources. In St. Pete, developers must have an approved site plan prior to demolishing a historic building. Tampa has no such protection, which is how two of downtown’s most historic buildings—the Strand Theatre and Maas Brothers—turned into a giant surface parking lot. Like the Maas Brothers demolition, there’s no guarantee that anything will be built on the site where the Tarr and Tribune buildings once stood.

Even with protections, historic preservation is still a challenge in a booming St. Pete, where, as I understand it, if a developer crosses the Howard Franklin, they’re awarded a condo tower just for making the effort. The Woolworth Building on Central Avenue (1929) was demolished last year, while several historic walk-up apartment buildings and bungalow courts dating back to the early 20th century either have been demolished or have a date with the wrecking ball.

Planners—the good ones—say you should be able to see the layers of a city’s history—its story—in its buildings. Indeed, historic architecture and “funky” older neighborhoods give you a sense of where a city’s been and where it’s going. In Florida, where everything is new and sprinkled with Disney dust, a good historic downtown—Ybor City, St. Pete’s Central Avenue, Miami’s Art Deco Historic District—can provide a bit of hip cache, a unique sense of place, along with a few tourist dollars.

But there’s more: Historic buildings, with their smaller scale and simple floor plans, offer adaptability. They can house dozens of different types of business over their lifespans; they’re often less expensive options for startups and small businesses, and pedestrian scale “main streets” offer walkability not found in more suburban areas.

If you’re looking for density, historic buildings offer that, too. On a per-square-foot and per-acre basis, older buildings and historic main streets are often more dense than new construction. The fact that you won’t need a five-story parking deck to rehab your four-floor walk-up helps the equation.

And, if you’re concerned about sustainability, you might be interested to know that, often, 30% of landfill waste is made up of construction debris.

With the loss of so many of its historic buildings, is it any wonder why people still see downtown Tampa as “dead?” You might say too many pages are missing for it to tell a good story.

There have been some successes in downtown Tampa over the last two decades: Developers repurposed the 1905 county courthouse into the Le Meridian Hotel, taking advantage of tax credits available for historic properties to save millions of dollars on the project. Developers of 220 Madison, another adaptive re-use project, reportedly saved $6 million thanks to historic preservation incentives and building code relief.

Over in St. Pete, Central Avenue, with more than 30 blocks of uninterrupted small-scale storefronts built mostly before the 1950s, hosts a daily parade of pedestrian traffic.

There are still some great buildings with great stories to tell in downtown Tampa and beyond. All we have to do is listen.