It began 20 years ago, when a handful of friends gathered for an informal picnic on the banks of the Hillsborough River. Then, as Tampa's lesbians and gays gained courage and visibility, their annual celebrations of pride and community grew and grew.

One high point: the convergence of pride weekend with an international gay and lesbian choral festival in July 1996. The festival brought more out-of-towners than any convention the city had ever hosted, and a substantial part of the city's business community went out of their way to welcome it. Mayor Dick Greco spoke to thousands of PrideFest revelers at the Tampa Convention Center, and television news highlighted a poignant scene in which a male chorus from Los Angeles sang "We Shall Overcome" in a cappella harmony to a cluster of silent protesters from the Ku Klux Klan.

By the turn of the millennium, Tampa Bay Pride promoters were touting their annual line-up as the largest gay pride event in Florida, and the second largest in the Southeast.

But there was something gnawing at the center of it.

A few people began raising questions about the producing organization's governance and direction; about its strong ties to the adult entertainment industry; and about the festival's relative lack of emphasis on politics and community-building, the original purpose of gay pride celebrations here and across the country. The small group who led the organization, meanwhile, grappled with the perennial challenge of producing a major event on the backs of time-stretched and easily distracted volunteers.

Now, after a disastrous move to Raymond James Stadium in 2002, the Greater Tampa Bay Pride Organization Inc. has collapsed under the weight of more than $300,000 in unpaid debts, as well as allegations of financial improprieties, conflicts of interest and drug abuse.

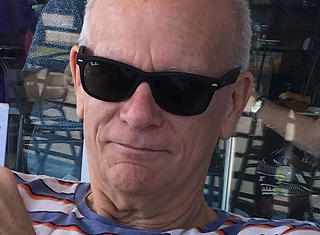

Donald L. Bentz, a diminutive man with a carefully coiffed mullet hairdo, long considered a community hero for his efforts behind PrideFest and other fundraising activities, had been the president of Tampa Bay Pride since the mid-1990s. Bentz hoped to escape the organization's problems by declaring it bankrupt and starting a new group to produce this year's events.

But those plans remain tentative — dependent, as Bentz acknowledges, on his ability to find enough commercial sponsors willing to overlook the bad publicity and still unanswered questions about last year's finances.

The possible end of Tampa's annual gay pride festival — mitigated in part by plans for a new event across the bay in St. Petersburg — may matter most to the area's estimated 120,000 gay men and lesbians.

But it is also an instructive tale for any nonprofit organization that purports to serve its community — how ambition, naivete, an overly insulated group of leaders and a community's changing tastes and expectations can make even the fanciest plans go astray.

Bentz and two other men who led the ill-fated former organization, meanwhile, are grappling with their own financial losses and the damage to their once solid reputations. Bentz says he lost $47,000 of his own money on pride events last year. Bud Bromwell says he's out $62,000. Jim Johnson claims a loss of nearly $40,000. None wants anything to do with the others.

Some gay community leaders have taken sides; others have chosen to stay above the fray. At the very least, says Brian Feiss, publisher of the gay-oriented monthly Gazette, "It's an embarrassment to the gay community."

Bentz acknowledges that his attempt to use bankruptcy to stay in the game has earned him critics. But, he says, "Tampa deserves a Pride. The new team understands we need to get back to the way we used to do it. After one bad year, my detractors want to crucify me when they were team decisions."

"He doesn't want to go out on a note like last year," observes Rick Walen, the Pride organization's former treasurer. "He has put the debt behind him. The question becomes, is it fair and is it right to leave people holding the bag, even if he's one of them?"

The Three Entrepreneurs

Local pride celebrations passed through a number of groups until the Greater Tampa Bay Pride Organization Inc. took the helm in the early '90s and established PrideFest. Bentz became president in '96 and helped build the event into quite the to-do. It included a parade, an array of parties, a business expo, celebrity guests and speakers, and its benchmark, the Wet Party.

For the last few years, that bash was held at the Florida Aquarium and drew 3,000 mostly gay men equipped with squirt-guns, energized by techno music and titillated by professional podium dancers who worked in the gay porn industry.