Have you ever sent an email or text message that you immediately wished you could take back?

And I don’t mean those drunk texts where you combined alcohol with fingers or thumbs to continue the lubricious party way after last-call. It seemed clever to you as you squinted at the smart-phone keyboard, chewing on your tongue, and holding one eye closed to bring it all into focus so you could type your ex- (or your soon-to-be ex) your wild poetry of love and lust, or hate and disgust.

That send button invites — no, it begs you — to hit it as your fingers itch for mere seconds, then respond to those synapses snapping in the reptilian part of your brain. The next thing you know, the vile and venom are coursing through the ether. I’m talking about those messages that collapse you into a fetal curl of disbelief the next day, or maybe as soon as the next second.

And I’m talking about a sent message — letter, email, text, or Twitter — perfectly legitimate, full of passion and emotion and likely very justified, but then straightaway slamming you with regret and remorse: Why didn't I keep my damn mouth shut? Since we send over 15,220,700 texts every minute of every day worldwide, some of those texts are probably lamentable and shameful. And it’s estimated that over 247 billion emails are sent every day. Some of those may also turn out to bite you in the ass. Mail sent via envelope and stamps can be just as regrettable, but it takes longer for the sender to sink into a swamp of despair.

When I saw the copy of Julian Barnes’ novel, The Sense of an Ending, on the bookstore shelves, I was reminded how writing and sending your precious thoughts hurtling through space can haunt you for the rest of your life. This very dilemma is at the core of the book's plot. It’s a relatively slender volume, but packed with meaning and hefty with remorse. Briefly, way back in college, Tony and Adrian are college buddies, Tony and Veronica are lovers, but they break up, and then Adrian and Veronica hook up and start making marriage plans. Tony is devastated, so he says, and writes a blistering letter, condemning them and trying to move on with his life. Tony essentially forgets his former friends and he forgets this letter. Years later, now in his 60s, once married, now divorced, retired and living alone, he sees this letter again, and he's shocked by his youthful outrage, cannot believe that he ever wrote something so vicious. He admits he'd lived the rest of his life totally oblivious and disconnected from truth, believing one thing about Adrian and Veronica, and discovering much too late that reality was something altogether different. He’s shattered. It's a powerful book (Booker winner, 2011), a mesmerizing meditation on aging, memory and regret.

Readers are shattered too because we likely recall some outrageous piece of business we ourselves are responsible for — whether handwritten note, typewritten letter, angry email, tossed-off text, even an injudicious tweet (much damage can be done in 140, or 280, characters) — and we’re haunted by our recklessness and sickened by our cruelty. What seemed justified in the moment later amounts to a petty and gratuitous effort to seek justice. Or attention.

Forgive me, but I recall one such blistering tirade I leveled against my father years ago. OK, OK, I was a teenager and he was a grown man, and children see things one way, often far removed from reality, especially when divorce is the inciting circumstance. After some perceived slight that I thought was the lowest he could go in terms of treatment of my mother and my siblings, I puffed myself up into a swollen posture of harrumphing, tongue-clicking umbrage. Suitably self-important, I fired off a terse note — written by hand, licked with a stamp, dropped into the mailbox — with the most offensive, grandstanding charge I could muster. “You are no more than a sire to me!” Yes, I was pissed and resorted to a barnyard metaphor conjuring up inseminating bulls and their insouciant, free-flung semen. I never heard back from my father, and maybe I saw that as the most dismissive of all. But not a day has gone by since then — and we’re talking 50 years hence, and my father is long dead, and my own son is in his 40s — without my wincing over that brief teenage J'accuse where such self-righteousness has morphed over time into regret.

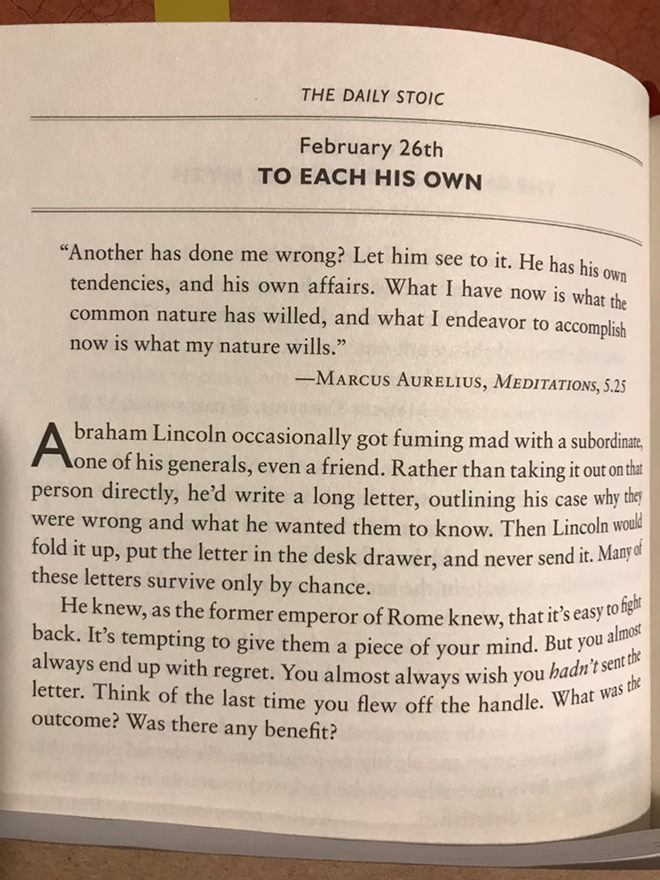

Marcus Aurelius and Lincoln were right (see below). Tony's letter, and my note to my father, would have been best left in a drawer or burned in an ashtray. Instead, Tony is haunted by his naive note and the likely consequences that he's only now discovering. And as for me and my callow letter, I find myself composing and re-composing my response and dropping it into the mail over and over, Sisyphus with a stamp. No sense of an ending here.

Ben Wiley, one of our Creative Loafing film reviewers, is also an advocate for paper and print. Dead trees, if you will. He volunteers at a local library bookstore and enjoys engaging with readers and their books. Our series BookStories will highlight some of these Ben, Book & Beyond encounters.