Storms have a way of sharpening your perspective.

My wife Julie and I fled when the NOAA map showed Irma turning up the Gulf coast. At 2 a.m. Friday we loaded our stuff, our son, one dog and a cat into our Subaru Forester. We made Birmingham in time for lunch.

I assured myself everything that mattered was in that SUV.

But I lied. For the next three days I checked social media compulsively. I never admitted to myself how much I care about my adopted city, my neighborhood and the friends who stayed.

Late Wednesday, after the 12-hour drive back from Alabama, I pried off the plywood, raked up debris and prepped for a night class on early Florida literature.

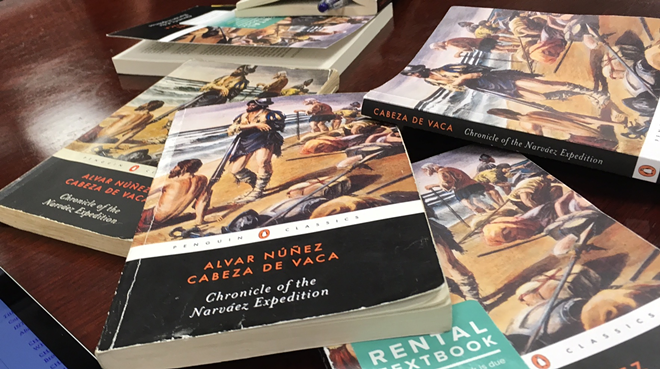

Weeks before Irma's first counter-clockwise spin over the Atlantic, I had assigned a classic storm story: Naufragios (Shipwrecks) by Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca.

Cabeza de Vaca (yes, head of the cow) sailed from Spain in 1527 as treasurer for Pánfilo de Narváez’s failed attempt to claim la Florida for God (and Spain).

The army of 600 hit bad weather off Cuba, then squalls in the Gulf. Narváez set out for northern Mexico; winds would push him to west central Florida. He landed somewhere off the Pinellas peninsula (exactly where, no one knows) on Good Friday, 1528.

With one eyebrow cocked, Cabeza de Vaca would chronicle the theatrical ceremony of possession. Narváez would raise the flag and stake a paper claim to the deserted village.

The starving army finds no food in the "poor and desolate" paradise of la Florida. Making the first of several bad decisions, Narváez splits his troops by land and sea. The Spaniards who travel inland follow the signs of Indians who want to get rid of them, to "Apalache."

On the panhandle, their fleet lost, the remaining soldiers cobble together rafts to coast back to Texas. After more storms, Narváez orders each man to himself, breaking the first law of military order.

The hierarchy dissolves.

The stragglers wash up off Galveston Bay, naked, desnudo, looking "like death itself." The weather carries Narváez to a watery grave.

Surviving Spaniards eat each other.

Cabeza de Vaca lives with coastal natives for six years. He barters and learns indigenous customs.

Along with three companions, including "Estevan the Negro" from North Africa, Cabeza de Vaca follows a trail of prickly pear cactus south and west, toward Mexico.

In Texas the tale gets really weird. One cold night, Cabeza de Vaca buries himself in a fiery pit. He rises the next morning like a wilderness Messiah.

The conquistadors become healers. They breathe on sick Indians and sign the cross, bringing back the dead. Cabeza de Vaca writes, “We could have left them all Christians.”

Eight years later, the four survivors stumble onto a Spanish outpost. Cabeza de Vaca journeys from Mexico City back to Spain. He chronicles the shipwrecks and peregrinations in a 100-page classic that Gabriel García Márquez once called the first Latin American fiction.

The book came at an opportune time. Cabeza de Vaca published in 1542 and 1551, when Spanish colonization was under debate. A half century of plunder left church leaders calling for conquest under the Cross, not the sword.

Cabeza de Vaca took these debates to heart (or exploited them to his own ends). He cast his storm story as a parable of Christian humility. He did so — make no mistake — to endorse his own claims as an Adelantado, or governor, in South America.

Motivations aside, a core message remains. That is, the moral understanding that follows a loss of power. The compassion that comes after a storm.

In class Thursday night, I asked my weary students to write their own storm stories. One student described a panicked drive with two kids to North Carolina, or maybe Baltimore (she and her husband were not sure). A student who has lived in Florida her entire life confessed to unexpected fears.

We talked about lost power.

In a storm story, we lose control. We lose power.

Cabeza de Vaca offers a parable of collapse.

At one point he describes crossing the Suwannee River. Juan Velázquez rides into the current. The Suwannee sweeps away the impetuous soldier.

Horse and rider, caballo and cabellero, both die.

The caballo becomes dinner. Cabeza de Vaca records the defeat with droll irony:

"The horse fed many that night."

As our president, governor and a Republican running for mayor of St. Petersburg refuse to recognize climate change, we need this lesson in humility.

Storms have a way of altering our perspective.

Bad weather off the Gulf taught Cabeza de Vaca that we are not always in control. He rethought how an empire should occupy these lands.

We might do the same.

Thomas Hallock is Professor of English at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg. When not working on "City Wilds" for Creative Loafing, he writes academic stuff, poetry and creative nonfiction. He is currently completing a book of travel essays about teaching, called "A Road Course in American Literature" (roadcourse.us). He lives in St. Pete and falls asleep a lot in his front porch hammock. Follow him on Twitter.