Here in the college collecting dust

books and professors huddle together

Professor Crookshank studying lust

talks with Miss Bailey about the weather

Is that a cirrus cloud you think?

Clouds is clouds Miss Bailey said

Look at that one tinged with pink!

Balls on pink she gaily said...

I was born in Brooklyn in 1932 during the Great Depression and lived there until the war ended in 1945, when our parents, upwardly mobile members of the Great Generation, moved to New Jersey.

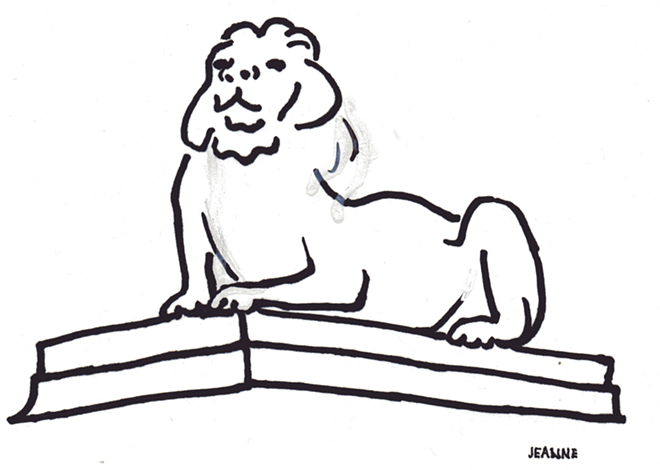

Although I was aware of those large and traumatic events, I was happy and secure. This was of course because of my parents, but I like to think it was also because of the lions, Patience and Fortitude, who flank the wide stone steps leading up to the New York City Public Library. I knew their names because they had just been announced — I forget exactly when — by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, and they were a matter of much discussion and some controversy. (For over 20 years they’d both been called Leo — Leo Astor and Leo Lenox, after the Library’s two founders, John Jacob Astor and James Lenox.) Patience is on the south side, Fortitude the north. These marble giants are huge, strong, and (to me, anyway) a bit smug as they stare out at Fifth Avenue, assuring us that all’s well: If you have any questions, young whippersnapper, come on in, mind your manners.

Although we never actually belonged to the New York Library, I loved to visit it, and still do. The stately columns; the decorative Beaux-Arts architecture; the breathtaking size of the Reading Room; the books that, like Wordsworth’s daffodils, “stretched in never-ending line;” the hushed ambience; and of course those lions, graced with lighted holly wreaths at Christmas, gave me an awe and appreciation of the importance of books and reading that’s never wavered. Although I’m writing this on my computer, I’ll be a printed book person until I die (maybe Friday). Editors and friends roll their distant eyes when they ask me to read something, and I request “hard copy” for anything longer than a sonnet.

I’ve had specific libraries that propelled me forward in their own ways. In my high-school library in New Jersey I was pretty much allergic to homework, but do remember discovering a edition of Shakespeare’s “The Rape of Lucrece,” illustrated with plump nude classical portraits, which gave me a greater interest in the Bard than one would have expected from a 15-year-old miscreant. To think of me as a rebel in those days would be to exaggerate my energy and focus, but I’d say that I had natural subversive sympathies.

Along that line, my first chapbook, The Rat Poems, illustrated with 24 crawling rats drawn by Jeanne, one for each hour of the day, was published in 1978. I was an unknown writer, and my first acknowledgment as a poet happened some years later in the bowels of the lovely Robert Woodruff Library at Emory University, where we spent one summer. I was getting my library card, and the elderly librarian stared at my name for a few seconds and then looked up, squinting thoughtfully. “Meinke,” he said. “Meinke... Oh, the Rat Man...” I was very proud, of course.

Though I’ve never seen the play, I was delighted to read one summer, in my carrel at Amherst College’s handsome Robert Frost Library, John Guare’s absurd one-act comedy, A Day of Surprises (1971), in which one of the stone lions, probably Fortitude, eats, in the Ladies Room, one of the librarians.

I assumed she must have been overly strict with the youngsters.

He wrote a sonnet to her breasts

an ode upon her tiny shoe

She wrote a memo to attest

that Herrick’s poems were overdue...

And when Miss Bailey turned him down

He wept real tears upon real rocks

and sang a melancholy song

to bored imaginary flocks

—Both quotes from “The Professor and the Librarian,” from Zinc Fingers by Peter Meinke (U. ofPittsburgh Press 2000)