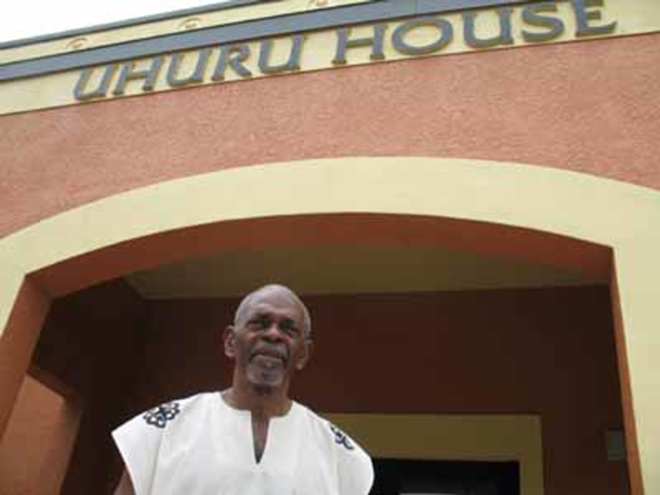

Who? Omali Yeshitela, founder of the International People's Democratic Uhuru Movement

Sphere of influence: Since Yeshitela (formerly Joe Waller) tore down a racist mural in St. Petersburg's City Hall, he has earned the respect (and ire) of St. Petersburg residents both black and white. Though once praised by high-profile politicians, he has distanced himself from City Hall and prominent African-American organizations in recent years. He continues to remain active in promoting African self-determination in other U.S. cities and Africa.

How he makes a difference: Some historians credit Yeshitela for ushering in the civil-rights movement in St. Pete, and even some white politicians admit he has empowered the city's black community. Through the Uhuru Movement, he has helped create retail stores, a gym, sports leagues and a radio station. Whenever there is an issue involving African-Americans and police, he becomes involved; a day after the shooting death of Javon Dawson by a St. Petersburg police officer earlier this month, he called a press conference condemning the shooting and telling witnesses that they could talk to a lawyer representing Dawson's mother.

CL: Describe to me what led you to tearing down the City Hall painting in the 1960s. Was it a turning point for you?

Yeshitela: I don't think tearing the mural down was a turning point for me. I had already come to a turning point. That's why I was down there. I was with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). I had made a clear choice that was the organization I would be associated with because of its black power demand, and because of its boldness and willingness to take on struggle where traditional civil rights organizations seemed unable to go.

We had been involved in letter-writing campaigns to the mayor about that mural, because the mural was horrible. It was an 8-by-4-foot display in the center of city power. It represented to us a relationship. It was like locking this relationship that they perceived as one between the African and white community that should exist forever. It was a caricature of black people. It wasn't a caricature of all the people; it was black people that were caricatured on there.

So after a series of letter writings and a number of marches down to City Hall, on one occasion, I walked into City Hall with five other Africans and tore it from the wall. I'll never forget this nice woman who was standing upstairs and she says, "You black bastard!" And we walked out with the painting.

This was where the whole concept of black power was still exciting to a lot of people around the world and police were unaccustomed to dealing with forces like us. So we started marching down the street carrying the mural. We made it to Central [Avenue] — I don't remember how far on Central — and this cop grabbed me. I'll never forget he was trembling. He grabbed me, and he was literally trembling. Others pulled me away and I ended up running down the street, dragging the mural behind me. I got to the back parking lot of Webb City and was stopped and arrested and went to jail.

It was an uproar. It was media from everywhere. They held some of the longest court hearings that went on late into the night. They were historic in terms of their duration into the night. I was charged with I think 11 offenses: disturbing the peace, inciting a riot, resisting arrest with violence, resisting arrest without violence, destruction of public property, just a whole array of charges were thrown at me. I think I was tried for disturbing the peace and probably destruction of public property and sentenced on one of those to six months. I spent a lot of time in the city jail first. They used to keep me isolated, because if I was with other black prisoners it created a problem for them. So they put me in this basement that they had in the city jail and on occasion they would bring little white students through on tours through the jail. And they would bring them down to the hole to see me.

It was an alarming thing for the city officials, and for the state as well, because what happened is it mobilized citizens throughout the state of Florida. Because it was kind of direct action that was talked about a lot philosophically at that time in the civil rights movement.

What was the turning point for you?

I used to — before there were sit ins and things like this, before Rosa Parks, when there was the little yellow line in the back of the city buses here — I refused to go behind the yellow line when my mother wasn't with me, to her dismay. I'm the guy who would go to Webb City and would refuse to drink out of the colored water fountains and would go on the fourth floor, where they had the snack bar. Africans on the first floor could eat as long as we were standing, but we could not eat at the snack bar where they sit down. I would go and do it and sit down and they'd kick me out and what have you. Until my high school English teacher learned what I was doing and sort of intervened to stop me from doing that.