The houses that line Edison Avenue in South Tampa, down by where the street meets Bayshore Boulevard, are lofty, old and mostly worth well north of a million dollars. But bubbling up beneath the gently sloping street is a water flow that’s nearly constant during the rainy season. The sidewalk is soggy and the cattails shooting out of the ground near one driveway are more evocative of a wetland than a quiet, upscale Hyde Park side street.

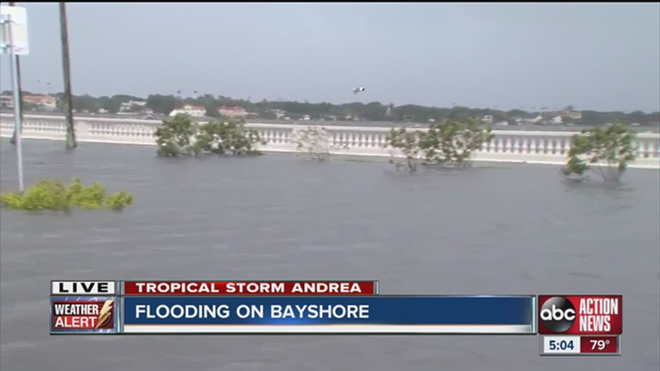

Edison is one of Tampa’s most flood-prone thoroughfares, along with Bayshore and most roads in South Tampa. Last Wednesday, when the obligatory afternoon storm turned into an uncommonly heavy deluge — a once-in-50-to-100-years event, say city officials — flooding got so bad that numerous stalled-out cars had to be abandoned along the roadways.

“Just the amount of rainfall per hour — I think it was anywhere from four to eight inches in a two-hour timespan at several of our rain gauges,” said Jean Duncan, director of the city’s Transportation and Stormwater Services division. “That is extremely high intensity.”

But even during smaller storms — and in some areas, even when it’s merely high tide — flooding is all too common.

“We’re low, we’re flat, and it takes big pipelines to drain these floods away in a hurry,” said Brad Baird, Tampa’s administrator of public works and utility services. “When you have over two inches in a two-hour period and the pipes are undersized it just takes time to drain away.”

How did we reach this point? Though a combination of poor planning decisions and dramatic land modifications in the early 20th century, inadequate infrastructure, and the city’s geographic orientation. Much of South Tampa was once either wetlands or a lake that was drained and filled in.

Some streets, ironically enough, were once creeks.

“Back then they viewed what we call wetlands, which we consider a precious resource, as swamps. Swamps were bad,” said Duncan. “They didn’t realize they’re just part of our natural ecosystem, they have a purpose and we have to balance that with where we might want to be building homes and businesses.”

Of course, the city can’t reverse the bad decisions of a century ago, but it can do things to lessen the intensity of flooding.

“So we can make a meaningful improvement if we do more,” she allowed, “but some areas are still going to always be vulnerable because of the geography or the historical drainage patterns that were there way before people came along and started building houses in these low areas.”

City officials hope to reduce the frequency of dramatic flooding events through a series of projects, but, given budget constraints and other factors, can only do so much. Later this summer they’ll ask the City Council to increase residents’ stormwater fees, which would be relative to the size and amount of impervious surface on a given property (the rate is currently $3 a month but officials hope to boost that to $6.83, or about $81.96 a year). The department now collects about $6 million in fees, and cobbles together the rest of its annual $18 million budget with money from the city’s general revenue fund, through partnering with entities like Hillsborough County and the Southwest Florida Water Management District and, sometimes, borrowing it.

“Part of our challenge is that we don’t have a dedicated fund source that is enough to support all the projects we have,” Duncan said.

In all, the city’s stormwater division has about $250 million in unfunded projects that could mitigate surging floodwaters in Tampa’s most vulnerable areas.

Such projects include replacing underground pipes with wider ones so the water would drain more quickly and installing pumping stations to quickly remove water from flooded areas.

Edison Avenue could benefit from larger piping underground, said Alex Awad, the city’s planning head.

That’s because the city’s first planners made some less-than-wise decisions when they laid out Tampa’s streets. Instead of sticking to higher ground and avoiding natural waterways, they placed Edison and a couple of other streets directly on a creek bed, replacing the natural water flow with underground pipes that often don’t have the capacity to handle high volumes of water.

“They followed creeks, put in pipes, covered it up and subdivided the property, so there was no thought as to, 'hey, maybe we’re going to get a hurricane that’s going to cause us problems,'” Awad said.

Other areas that could use a little help include the intersection of Dale Mabry and Henderson, Hillsborough and Nebraska avenues in southeast Seminole Heights, Drew Park, and Swann Avenue in Old Hyde Park. There, a lake was drained of most of its water to make room for development, which meant the water that naturally washes into it during storms has nowhere to go,

While the wish-list is long, the city has gotten a head start in some places.

Near Busch Boulevard at 30th Street, a flood-prone area, the city and county partnered on creating Duck Pond, a large stormwater treatment area with two pumping stations.

On Alline Avenue, a few blocks north of Gandy and west of Bayshore, an area that was once a lake, the city built a pumping station in 2013 that was cleverly disguised as a house, front lawn and all, for $4.8 million.

The projects aren’t going to mitigate all flooding, Duncan warned. After all, the city plans for weather events that are essentially five-year storms, and requiring that everything be equipped to handle a 50- or 100-year storm would be cost-prohibitive (the one exception being interstate roadways, which are of course elevated).

“We design for more the expected frequency of things as opposed to some very unusual circumstance,” she said. “Because the higher level your design, the more your cost goes up.”

While many frequently flooded areas in the city have a potential fix, there’s at least one that probably can’t be corrected: Bayshore Boulevard.

After Tropical Storm Debby in 2012, plenty of people fell for a Photoshopped image of a shark swimming along Bayshore.

That’s probably because they know the road was built at such a low elevation that in some areas the road floods at high tide.

The boulevard is barely two feet above sea level in some places, but high tide can bring the water level up to three feet.

The only ways to fight flooding on Bayshore would be to elevate the entire roadway or install a taller seawall around the entire peninsula, Awad said.

“It’s not cost beneficial and the residents probably wouldn’t want it,” he said. “[They] are not going to want to see a higher balustrade and not have the view of Bayshore. So they’re willing, in my opinion, to sacrifice a little bit of flooding for the view that they have when it doesn’t flood.”

And, of course, most people living on or near Bayshore seem to be well-enough situated economically that they can handle a little flooding.

“You will be inconvenienced maybe where your car stalls out and you can’t get home, but in the scheme of how many days a year does that happen, is it worth putting up with that or not?” Duncan said.