You may know a folk artist. Hell, you may be one. It doesn't take much: a pen or brush or needle in your hand, a few hours to spare between shifts on the clock or tasks around the house, and something in your mind that's absolutely, positively burning to be said. That last piece, of course, is the rare element: It's what makes art art, instead of something else. It's what makes it hard to turn away.

Walking into Self-Taught Genius: Treasures from the American Folk Art Museum, the powerful new exhibit at the Tampa Museum of Art, you're confronted with dozens of examples of that burning-to-be-said material, and you will definitely not want to turn away. The show is an impressive selection from the American Museum of Folk Art in NYC. Tampa is the last stop on a seven-city swing, and anyone with an taste for homespun strangeness would do well to check it out before it heads back to Manhattan on January 19.

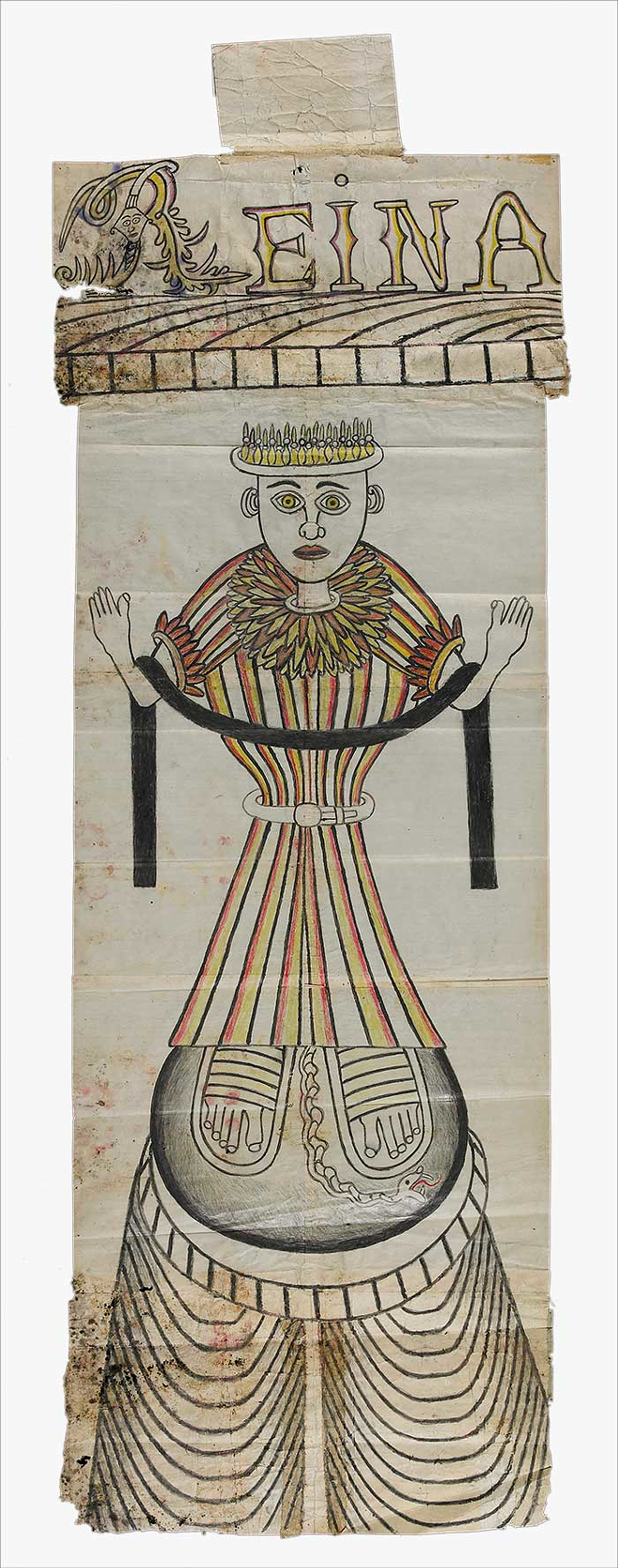

The Big Apple is a funny place to stockpile art that is defined by its distance from the Art World mob. Especially since so many of the artists included here come from America's margins — New England recluses, Alabama sharecroppers, Mexican migrant workers. But far-flung vision, not geography, is what really unites these artists. The selections range from practical (if unusual) furniture to bizarro diagrams in ballpoint pen. There are wood statues, yarn mummies, phrenological heads. The show is amazingly broad, and yet it all hangs together—there's something particularly American about that.

The show's subtitle is "Treasures from the American Folk Art Museum." The "treasures" statement is well-earned, but vulnerable. One man's trash… the cretins will chuckle. And indeed, much of what you find here could feasibly, at one time or another, have been called junk. Consider Mary T. Smith's yard-signs, glaring totems of protection painted on corrugated metal. Or the work of George Widener, a "calendar savant" who drew a hypnotic, heartbreaking tribute to the casualties of the Titanic…on paper napkin. Or any of the several weather vanes, pinnacles of buildings which have long since crumbled down. These are the wrong materials, by people in the wrong zip code, with all the wrong ideas about what art is supposed to be. They did not get the memo: Art moves onward, ever onward, and the unfashionable get left behind.

According to the forward-thrusting progressive model of art history — as doled out by the art schools, etc. — we should all be making only conceptual art about conceptual art by now, or jokey balloon sculptures (and no one should be painting at all, because painting is dead, haven't you heard?). As for the artists who did not get the formal schooling that tells people these things: tough tits, you're excluded. It just so happens that many of the excluded parties are women, and people of color. They're late to the game.

Well, if painting is Over, nobody told the artists in this show, many of whom were painting like their lives depended on it. Take Bill Traylor, sometimes called a Naïve Artist. One of his smallish untitled pictures hangs near the back of the exhibit, poster paint and pencil on cardboard. In it a black dog chases black children around and around, while a black tophatted man and a black crow look on from the high ground. Traylor was born during slavery, lived as an impoverished sharecropper in Deep South, raised "twenty-odd" children, and went on to make these incredible images — what exactly was this guy "naïve" about? Not a damn thing, and if the details of his life don't convince you of that, then the contents of his pictures should. What made him an "outsider" artist? To the contrary, he created from squarely inside the intensities and difficulties of day-to-day life. He was the ultimate insider.

Naïve Art, Outsider Art, Folk Art. The epithets are necessary, maybe, but all ring false. Most demeaning, maybe, is the term Useful Arts.This is supposed to apply to the homey domestic stuff, quilts and chairs and such. But the scope of "Self-Taught Genius" proves that all art, from the commonplace to the wildly visionary, is Useful. As another self-taught genius, Thornton Dial, said: "I plan for my art to help a person think. Everything a artist make supposed to help a person handle his life better." What could be more useful than that?