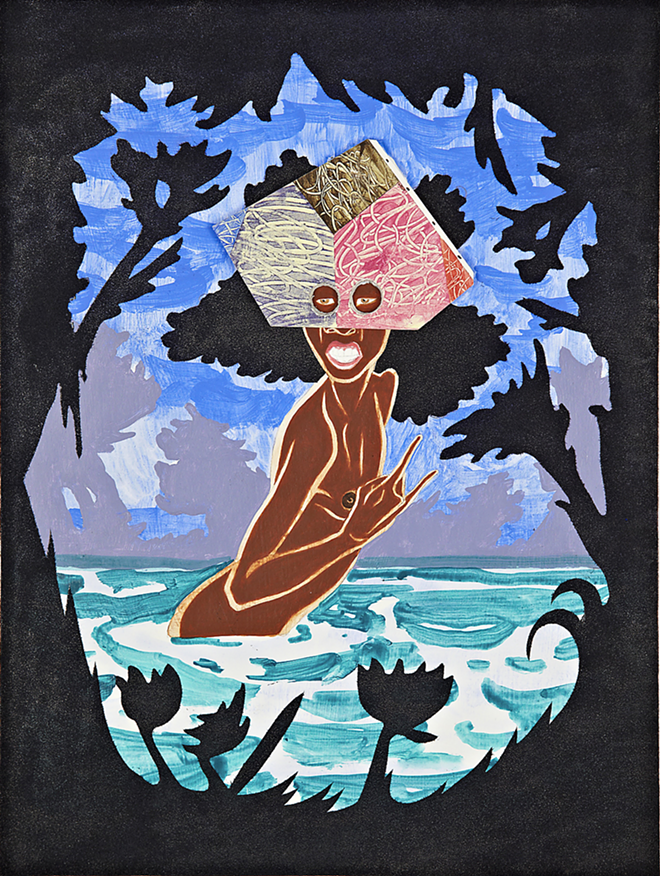

Women in William Villalongo’s paintings are enigmatic creatures. Naked as jaybirds or scantily clad in fur bikinis, they strike Bond girl poses in woodsy, watery landscapes, construct primitive shelters out of abstract paintings, and occasionally come sliding out of a zebra’s vulva like a newborn babe. The subjects of a tropical Gauguin painting by way of Foxy Brown, they bare their breasts but coquettishly conceal their faces with miniature canvases that could be castoffs from the likes of Ellsworth Kelly or Frank Stella.

Nipples as hard as their badass attitudes, it’s hard to tell if these ladies kick ass or if they’re meant to be ogled.

“It confuses people,” Villalongo admits. “They want to know if I’m a feminist or a horny pervert.”

His indeterminate position between the two poles makes Villalongo’s work difficult to turn away from. (Perhaps, like some of us, he is simply both a feminist and a horny pervert.) Aficionados of modern painting will recognize that he adopts a favorite subject of painters including Cézanne, Matisse and Picasso — women bathing or otherwise communing sensuously with nature — and imbues it with a healthy dose of postmodernity: gender and race politics; a whiff of post-apocalyptic survivalism or alter-dimensionality; and a winking self-referentiality.

The heady mix can leave viewers feeling uncertain about how to feel in front of images that exoticize and objectify women as a way of parodying past traditions of exoticizing and objectifying women.

“The only way to deal with it is to go head on and jump into something problematic,” Villalongo says.

Visitors to the University of Tampa’s Scarfone/Hartley Gallery can decide for themselves this week when UT celebrates an exhibition of Villalongo’s paintings and the conclusion of his 11-day residency at STUDIO-f, UT’s collaborative printmaking workshop. A reception and open house on Friday offer a rare opportunity for the public to meet and chat informally with a rising star in the art world outside Tampa Bay about his latest work. (Villalongo, 37, who lives in New York and teaches at Yale, has also been an artist-in-residence at the prestigious Hermitage Artist Retreat in Sarasota.) In addition to the dozen-plus paintings included in the exhibition, a series of 10-15 silkscreened monoprints that he has been producing at STUDIO-f with the help of printmaker Carl Cowden III will be on display.

When I visited last week, Villalongo was in the midst of composing each layered silkscreen print. The central image depicts a woman looking up at the sky, her neck arched back with a fabulous afro crowning her head, inside of which the outline of a brain is visible. Above her, a grid folded into the shape of a truncated cone symbolizes a channel into another dimension, according to Villalongo — to wherever and whenever his babes of color, who turn up in a multi-ethnic variety of hues but rarely look like white chicks, frolic. Creating the series is like performing a variation on a theme: in each one, Villalongo combines unique elements, like hand-painted sections or shifts in color, with silkscreened layers so that no two are alike.

His paintings, which reward a viewer who looks closely and over time with surprises, are fashioned in much the same manner. Figures are painted onto paper with flesh-toned paint in a flat, almost dimensionless style, lending them the look of lithe woodblock prints. Then these paper women are collaged into verdant, lake-filled landscapes on wood boards, vignetted by a swirl of flora and fauna rendered pitch black like Victorian cut paper with a coat of velvet flocking.

It’s painful not to touch them.

As for the painting masks Villalongo’s women wear, these are further collaged on as a bit of painted foamcore that stands off the paper, and through which piercing eyes peer. Part homage and part send-up of the mid-century American abstractions that seem still to rule the world of high-brow painting, Villalongo invokes them with the same ambiguity that he applies to the female figure as a cliche ripe for having some serious fun with. He asked me during my visit: What if there were another dimension where modernist painting were the height of primitivism?

There is such a curious world, and it comes from Villalongo’s hand.