The events of September 11, 2001 were a tragedy for all Americans, and it's only natural that we look for ways to mourn and share our sorrow. Anne Nelson's The Guys provides just such an opportunity. In its tales of four firefighters who gave their lives in the Twin Towers, it allows us to reflect on their sacrifice, recognize their humanity, and grieve for their loss. This is theater in the ancient sense: as a religious act, a call to fundamentals.

For this reason, some theatergoers may feel disappointed. There's no real conflict here, no suspense, no transforming climax. The acting is first-class, but the emotional range shown is narrow.

Still, that's right for an exercise that's as much an act of communion as it is a drama. The Guys is about acknowledging, celebrating the dead. If the experience is less than cathartic, still it's meaningful — and comforting.

There are only two characters in the play — Nick, a captain in the New York Fire Department, and Joan, a writer who's taken it upon herself to help him write eulogies for the funeral at which he must speak. Joan is just what Nick needs — someone respectful and cautious, able to draw out his memories of his fallen comrades, and talented enough to turn those disordered fragments into coherent paragraphs.

Although Nick lost eight men in total, we only hear about four: Bill, the quiet Irish firefighter who "looked like a plumber" and had the opinions of a food critic; Jimmy, the new guy, who was lovingly razzed by the senior firefighters, and for whom 9/11 was his first and only fire; Patrick, whose life was organized around work, church and home, and who was a leader, not a boss, to all the men who looked up to him; and Barney, the cut-up, who collected antique tools and whose romantic dream was to one day meet a woman welder.

As Joan translates these details into fine, but not too fine, phrases, Nick loses his anxieties: maybe he will, after all, be able to address the bereft families with words equal to the occasion. And New Yorker Joan, whose pain for her damaged city also needs assuaging, finds some solace in her labor. She lets us know, though, that she'll never have what she most wants — to rewind the tape, to have the towers miraculously rise again along with all the lives they once seemed to shelter. Take it from a writer to doubt the efficacy, finally, of words.

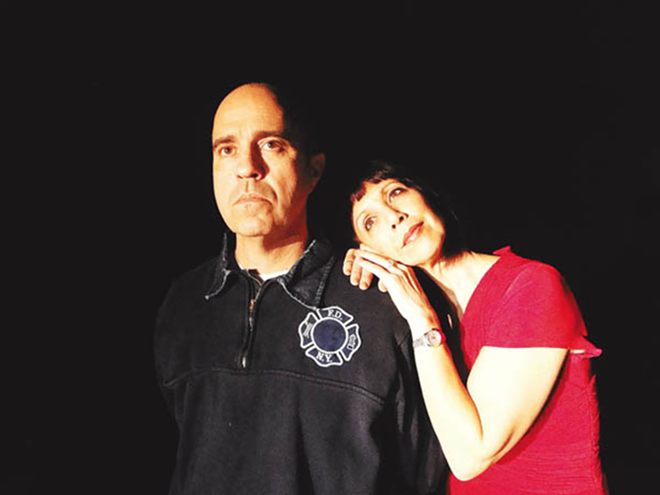

Paul Potenza is Nick and it's another top performance from a mightily talented artist. Everything is just right here, from the bafflement and sadness which he first brings to the meeting with Joan, to the love and humor that emerge as he describes the lives of his fallen men. If I hadn't seen Potenza shine in so many utterly different roles, I might feel that Nick was the part he was born for, the one that required the least "acting." But of course, it's precisely Potenza's magic that makes this melancholy firefighter seem so authentic.

As Joan, Roz Potenza (they're husband and wife) is also completely convincing. With seeming ease she persuades us that she's a transplanted Oklahoman who's happily become a New Yorker, an interpreter who in seconds can turn an aside into an encomium, a caring soul who can speak, for us all, of her grief. The Potenzas even manage to make the one false note in the play seem thinkable. This is a tango that the two characters share for no credible reason, and which threatens to break not just the mood but all logic. Not to worry: the dance is performed with such tentative, moderate humanity, it seems almost appropriate. These two fine performers can make even the incredible seem likely.

The Guys is scrupulously directed by Shawn Paonessa on Brian Smallheer's elegantly simple set, in which three distinct playing areas are backed by oddly shaped cutouts, quietly suggesting devastation. The show only takes 70 minutes without intermission, but that seems about right. Roz Potenza is also responsible for the felicitous costumes, suggesting a Northern climate as autumn approaches. Smallheer designed the evocative lighting.

Of course, no play can sufficiently commemorate an event as tragic as 9/11. But maybe that's The Guys' secret: it's small, unassuming, deliberately limited in scope. Aspiring to little, it doesn't insult us with its ambitions. Like a carefully chosen kind word, it's brief but soothing.

We all lost a lot on that day.

But it's the virtue of The Guys that it keeps its canvas small.