Kirk Ke Wang: Yes & No

Runs through July 12 at Opera Central, 2145 First Ave. S., St. Petersburg.

On view during Bella Voce 2015, Sat., May 9, 5:30-11 p.m., in conjunction with St. Petersburg Opera’s upcoming production and the gala’s theme of Turandot and ancient China. The show in its entirety will also be on view during June and July’s Second Saturday Art Walk in St. Petersburg. Works can also be viewed by appointment; email [email protected].

Shanghai-born Kirk Ke Wang has learned to cope, and ultimately embrace, a life filled with ambivalence. The 54-year-old contemporary artist deals with the dilemma most immigrants face: missing loved ones, an incomplete sense of self, and the pangs of nostalgia that linger after finding success and assimilating elsewhere. Add to that the realization of inequities in both one’s homeland and adopted home.

Though he is well-established in the U.S. — Wang holds two MFAs, has a wife and two daughters, a co-op in Manhattan, a home in Shanghai, a nonprofit Tampa studio and a tenured professor position at Eckerd College — the sadness of a life left behind still haunts the artist, and inspires him.

“Yes & No deals with the dichotomy of the opposites in my life,” Wang shares during a visit to Opera Central, St. Petersburg Opera’s downtown annex, where his exhibition Yes & No remains on display amidst red lanterns about to be hung for the Turandot-themed Bella Voce Gala this Saturday. The setting is unconventional but mutually beneficial for the artist and opera fans, who can both use the exposure — all thanks to the efforts of St. Petersburg Opera curator Mirella Cimato Smith, who plans to show art in conjunction with Opera Central events on a regular basis. Wang created the collection earlier this year for South Tampa’s CASS Contemporary Gallery as a more installation-based show, which he scaled down and relocated to Opera Central last month.

If you’re familiar with Wang’s past works, expect to see more convergences of social consciousness and child’s play (toys, candy, cartoon characters). In 2013, CL Visual Art Critic Megan Voeller wrote about Sugar Bomb, Wang’s installation at Hillsborough Community College-Ybor. The show made “serious comedy out of political encroachment” with more than 30 bombs, each handmade by the artist from Chinese, Cuban and American found objects, which hung from the gallery ceiling. Gummy bears, Skittles and Cuban sugar filled the missiles, inviting the viewer to consider how people are seduced into consuming and how culture can be as invasive as missiles.

Another opportunity for Wang to be playfully experimental with serious subject matter, Yes & No challenges viewers to avoid settling on easy interpretations of the show’s large-scale mixed-media paintings. The beauty of old Chinese illustrations is paired with splashy imagery from pop culture and paper cuttings. There’s even a portrait of Wang’s wife created with with paint drips; he created it while holding an old photo from 1984 with no sketch to guide him. Each piece has contrasting moods and an East-meets-West component, refraining (for the most part) from didactic messages.

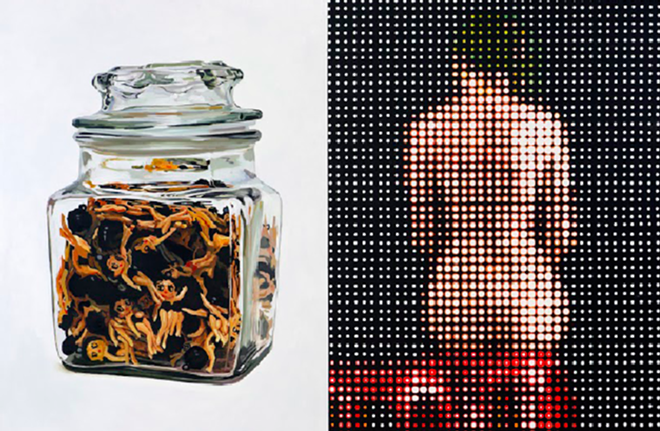

The iconic Betty Boop, who showed up in Sugar Bomb, makes a repeat appearance in Yes & No. The vintage cartoon character comes with a double entendre: Betty Boop is a symbol of our childhood but a little risque, too, indicative of an exploration of sexuality and exploitation that recurs in other works. On the left half of “A Jar of Betty Boops,” a sealed glass jar — the plain glass type you’d find at Walmart — is filled with small plastic Betty Boops. Wang says the work was initially inspired by 2012 presidential candidate Mitt Romney, who bragged about his “binder of women.”

“Sometimes in our society we appreciate women and talk about gender equality, but in reality it’s just like Betty Boops in the jar,” Wang says. “They’re nice to look at but the lid is closed on them.”

On the right side of the work, a female figure made up of hand-painted circular pixels sits gracefully on a chair with her back to the viewer. Wang uses a technique here that recurs in other works; it’s created to be photographed with a cellphone as a commentary on instant-gratification artmaking, and it speaks to Wang’s dual fascination with painting and digital art (which he also studied in college). The dotted woman is a Chinese toymaker who created the little Boops in a factory, whom the artist chose to present anonymously. An ironic sidenote: Wang returned to visit the model later and learned that the she didn’t earn enough on the job and moonlighted as a prostitute, a story that adds relevance and a stinging touch of pathos to the work.

In “Chained Bird,” Wang offers a tribute to famous Chinese contemporary Ai Wei Wei, who has been forbidden from leaving China since 2012 and has been under constant government surveillance. On the left, we see a hand-painted pixel representation of Ai and on the right, a shackled bird that’s looking up to the sky, hinting at a hope for freedom. “I’m optimistic about it,” Wang says. “I think he [Ai] will be free one day.”

The painting, as with most of the others in the show, combines oil and acrylic, the latter a nod to his late friend and a beloved local artist.

“I used to use only oil but now I relearned how to use acrylic because Theo [Wujcik] always used acrylic,” Wang says with a wistful smile. “Caged Bird” was initially created when Wang and Wujcik showed together at the Polk Museum of Art in 2012. Wang later wrote on his Facebook page: “Theo likes the dots.”