I thought I had reached the point of no return with Kind of Blue. Having listened to the classic 1959 Miles Davis album so many times, having owned it in so many of its reissued iterations, I suspected, feared even, that I might never desire to hear it again.

What was once my go-to platter for midnight mood music had slipped considerably down the list — and for no other reason than burnout. I hardly thought that yet another reissue of Kind of Blue — this time a deluxe 50th Anniversary Edition — would rekindle my passion for it. But somehow it did.

And I didn't even get the full deluxe box, which includes, staggeringly, the original album on CD, along with several studio segments, breakdowns and false starts; a second CD that compiles recordings by the Kind of Blue ensemble from 1958 and a 17-minute, previously unreleased concert version of the lead track "So What," recorded in 1960. The new set also includes a riveting 55-minute documentary DVD on the making and impact of Kind of Blue.

These three elements were what the kind folks at Sony Legacy sent me in the mail. I did not receive the 12-by-12-inch full color, 60-page book or the LP on 180-gram blue vinyl. I just couldn't bring myself to plunk down the $109 retail to own the extras. (The LP should be available by itself next year.)

So some of you might be wondering: What's the big deal about Kind of Blue? Most anyone with any awareness about music has at least heard of it. Probably more non-jazz fans own it than any other jazz album. Sony touts it as the best-selling jazz album of all time, having recently crossed the 4-million threshold. Rolling Stone put it No. 12 on its rock-intensive list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.

Reams of scholarly words have been spilled about the importance and appeal of Kind of Blue, and I won't try to recap them here. Let me try to explain it through personal experience.

In the late 1970s, not long out of college, as a new resident of St. Petersburg with a lot of spare time on my hands and a lousy job, I was in the process of becoming a jazz fan. I had evolved from Spyro Gyra to Weather Report and Pat Metheny, and a friend's temporary loan of her jazz collection (which, incidentally, didn't include Kind of Blue) sealed the deal.

A job at a small local music magazine followed and my jazz fandom continued to grow, aided by the promo copies of LPs sent to me by record labels (including plenty by Miles Davis). One day in the very early 1980s, I was chatting about jazz with my co-worker, and he asked if I'd heard Kind of Blue. I said I hadn't, to which he responded with something like, "What the fuck is wrong with you?"

By that night, I had procured a copy, and it was love at first listen. The music was slower and more sensual than the bebop and post-bop I had been consuming. Kind of Blue evoked a late-night back alley — but in a nice neighborhood.

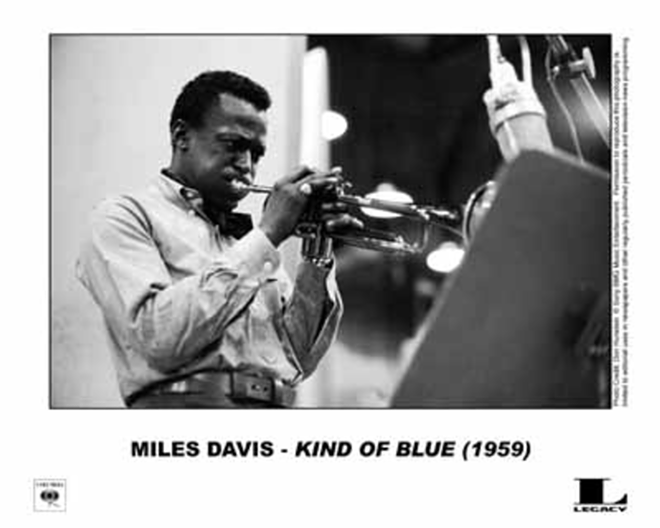

As a pure convergence of talent, the lineup on Kind of Blue stands up to any in jazz annals: John Coltrane on tenor saxophone, Cannonball Adderley on alto sax, pianist Bill Evans (Wynton Kelly on one song), drummer Jimmy Cobb; bassist Paul Chambers — and, of course, Davis on trumpet.

The tunes are built around spare scales rather than cascades of chords, which gives the music a simplicity and accessibility that have been big factors in it standing the test of time. Kind of Blue washes over you, seduces you. Moody, dark, melancholy but somehow reassuring. The album has a consistency of feel — there are no fast burners on the record — that's another one of its strong points, but within that consistency is a wide emotional range. Most of this comes from the character of the soloists.

The tunes essentially start with short, riffy (and catchy) melodies that give way to a round of extended solos by Miles, Cannonball, Trane and Evans (or Kelly); the band then restates the theme and the song ends. That's pretty much a pro forma jazz approach. Each of those soloists, though, makes a profound impression in each and every song.

Jazz critic Francis Davis, one of the annotators on the new box, makes an intriguing point that I had never considered. Because improvising over scales, or modes, was effectively new to these players, and because they entered the studio without any preparation, some of their playing sounds tentative.

That doesn't, on its face, sound like a good thing, but Davis writes, "Coltrane benefited from a little slowing down at this point in his career, just as Adderley needed a safeguard against glibness. In fact, a good deal of tentativeness on the part of everyone but Davis and Evans is one of Kind of Blue's most beguiling aspects."

Despite this agreeable sense of caution, the basic character of each soloist emerges and gives the record more emotional heft. Miles: unhurried and introspective, each phrase sublimely crafted for maximum impact with the fewest notes. Evans: self-effacing and spare. Coltrane: still restless and searching through his tentativeness. Adderley: sweet, bluesy, the happiest-sounding of the lot.

Kind of Blue became the mother lode. I would subsequently bring other landmark albums into my orbit: Coltrane's A Love Supreme, Oliver Nelson's The Blues and the Abstract Truth, Sonny Rollins' Freedom Suite, Bill Evans Live at the Village Vanguard and hundreds of others. But Kind of Blue remained the one.

Until the last two or three years, when I thought I'd heard enough of it — too much of it — for the music to have anything more to offer me.

I'm glad I was wrong.