But last weekend, the specific location information his company, along with the general public, received from the Tampa Police Department (TPD) suddenly changed.

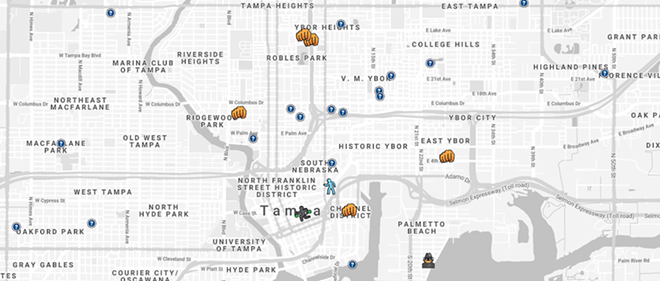

Locations for reported crimes switched from specific blocks to a less trackable grid format, which can encompass several square miles around where the incident occurred. Previously, SpotCrime's map would show the block the crimes happened on, for the benefit of public safety.

Now, TPD's changes make it difficult for SpotCrime's Tampa map to function properly.

"I immediately asked myself, why would they [TPD] restrict access to information that could help protect its citizens?" Drane told Creative Loafing Tampa Bay. "Hiding this data makes no sense. Our aim is never to sensationalize this data or harm any person or department, it's just to inform."

Drane, President of SpotCrime, said that the information can be very important for public safety, like when tracking child predator activity in an area. He gave the example of other cities it tracks, where suspects had allegedly been caught preying on children.

"We want that information out, so that if there is some perpetrator going after young kids, we want the community to have knowledge and to protect children in that area," Drane told CL.

Drane says that the company has 30,000 subscribers in Tampa that rely on the crime information for safety. The company sends out around 300 million emails a year to people in the U.S. about specific crime details and trends, using the data from thousands of police departments.

But he and Vice President of SpotCrime Brittany Suszan can only do their job properly when police departments are reporting their crimes in a transparent way.

Across major U.S. cities, TPD is one of the only police departments purposefully becoming less transparent, Suszan says.

"Asking for this kind of data is not a novel idea," Suszan told CL. "Newspapers have used this data for crime blotters for a long time."

Neighboring St. Petersburg and Orlando still report their crimes by block, and SpotCrime's map functions correctly in those cities.

Nevertheless, TPD has suddenly chosen not to share the crimes by block, and one of its main arguments for not doing so is Marsy's Law, which was passed in Florida in 2018. Under the law, the identities and information about crime victims are protected. Police departments have also used the law to shield the identity of officers involved in incidents like fatal shootings, classifying cops as victims in certain cases.

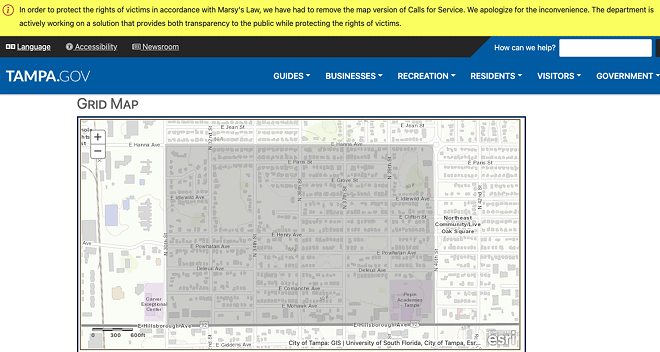

TPD said that due to Marsy's law, it's had to change reporting of crimes from the block level, to the grid level.

A city "grid" encompasses several city blocks, making it less transparent as to where a crime occurred.

"We were working with the program developer to fix a technical issue discovered on the site last week, to enhance the protections for Marsy’s Law victims," TPD wrote to CL in an email statement. "The interactive Crime Map has since been restored."

TPD then confirmed that the data is now presented at the grid level, as opposed to the block level. The public calls for service website reflects this change, as of Friday afternoon.

City Of Tampa

An example of the new way TPD reports crime location by grid on their public calls for service feed.

The legal issue here is that, as Suszan points out, within Marsy's Law, there's no provision that says that general public crime information should be affected by the law. Marsy's Law for Florida, the group that pushed to bring the bill into law, even said so in a press release in 2019.

"There are no provisions in Marsy’s Law for Florida that prevent the release of details of a case, including general information on where crimes have taken place," Marsy's Law for Florida wrote.

"There are no provisions in Marsy’s Law for Florida that prevent the release of details of a case, including general information on where crimes have taken place," Marsy's Law for Florida wrote.

And while protecting the location of victims for their safety is certainly important, block level reporting does not give a victim's exact location. And there are reasons why reporting at the block level is important for the safety of the community, as Tampa lawyer Mark Caramanica explained to CL.

Caramanica specializes in media law, copyright and civil litigation. He also held concerns about the new mapping process.

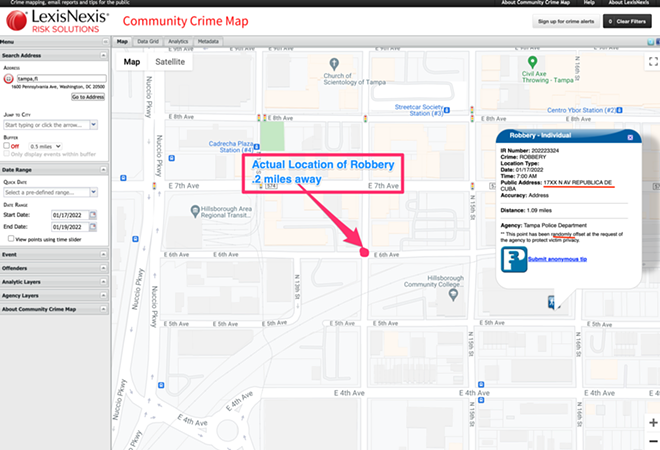

Caramanica called TPD's move on the mapping an "overreach", and said that that even on private mapping software like LexisNexis, the locations of crimes are currently offset. When he opens the LexisNexis map and views a pinpoint marking a call for service or a crime, the system makes it clear that the crime did not actually occur in that area, as part of TPD's changes.

c/o Colin Drane

A screenshot of LexisNexis, marked by Colin Drane, shows that crimes are now being reported miles away from their actual location.

"The public only suffers because of this," Caramanica said.

TPD is not the only Florida law enforcement agency that's erroneously used Marsy's Law to conceal previously public data. In a guest column for the University of Florida's Brechner Center for Freedom of Information, Suszan pointed out that three sheriffs departments—Polk, Lake and Pasco—have used the law as a defense for hiding data.

In the same column she pointed out that a 2017 decision by the North Dakota Attorney General decided that a victim must opt-in to prevent any disclosure of information related to their case.

The A.G.’s ruling also limited the type of location information that can be withheld at the victim’s request primarily to pinpoint address numbers and building names, and even went as far as declaring that names aren’t secret. Now In North Dakota, Marsy’s Law no longer hides the facts of a crime.

The A.G.’s ruling also limited the type of location information that can be withheld at the victim’s request primarily to pinpoint address numbers and building names, and even went as far as declaring that names aren’t secret. Now In North Dakota, Marsy’s Law no longer hides the facts of a crime.

CD Davidson-Hiers, Programs Coordinator for the Florida Center for Government Accountability, a non-partisan 501c3 that seeks transparency in government, said the group is seeing an "alarming lack of uniformity throughout Florida" in how law enforcement agencies are reporting crimes.

"Some agencies release street names but redact house numbers. Some agencies redact entire addresses, even if crimes occurred in public areas where the address would not disclose the victim’s home. Some agencies are now charging fees for staff to review records as simple as crime blotter sheets when the public requests access, reviewing for Marsy’s Law exemptions," she wrote.

Davidson-Hiers said that the unintended effect is that communities get left with no way of knowing where crimes are being committed, or who may be affected.

She said that the lack of uniformity in implementing the law has, "A negative impact on the public’s ability to make informed decisions about housing, workplace and education and also affects the ability of communities to find solutions to the issues that lead to crime in the first place. And, equally concerning, it erodes public trust in law enforcement."

According to Drane, agencies changing from block to grid reporting almost never happens because crime is going down. In his eyes, concealing the data only benefits criminals and upper management in law enforcement departments that went to manipulate data to their advantage.

Drane said that he ended up having a conversation with two TPD officers earlier this week about the changes: Cpl. Derek Lang and Richard Blasioli, who was a captain as of 2018.

He said his first call with Blasioli was "terrible" and that the officer said he knew nothing about their mapping system. When Drane mentioned victim concerns, he said that Blasioli proceeded to accuse him of "profiteering off of their crime data."

Later in the day he got a call from Lang. This call was the opposite of the morning call, he said. Lang said they originally had to make changes because of a technical error, echoing TPD's statement.

"Despite these technical complications, TPD had enough time and programming prowess to change the block addresses to grid locations," Drane said.

Drane and Suszan say that their next steps are to call on the city to do something about this problem. They've spoken with a city council member (but didn't want to disclose who just yet) and are planning on amplifying their message to the city to be transparent, as just about all other major cities in the U.S. are.

Drane says that changing to grid mapping is an "absurd solution" that "insults the intelligence of the public."

He referenced what he calls the "trust quotient."

"When you remove data, you lower that trust quotient, you lower safety for the public," Drane said. "If you increase transparency, you increase the trust quotient with the community."

He referenced what he calls the "trust quotient."

"When you remove data, you lower that trust quotient, you lower safety for the public," Drane said. "If you increase transparency, you increase the trust quotient with the community."