I’m searching for the Fountain of Youth.

This is, of course, a quest as old as La Florida itself. Except maybe not. For more than a century, the legend of Florida’s magical youth-giving spring has woven its way through the state’s aquatic attractions, tourist literature, and a whole suitcase full of Florida place names—including the odd little corner of St. Petersburg I’m seeking. The story reputedly begins with conquistador Juan Ponce de León, who gave Florida its name (from the Spanish “Pascua Florida” Easter celebration) after sighting its Atlantic coast in April of 1513. His expedition went on to survey the “island,” which they quickly discovered was not an island, coasting from the vicinity of present-day St. Augustine to somewhere near Charlotte Harbor.

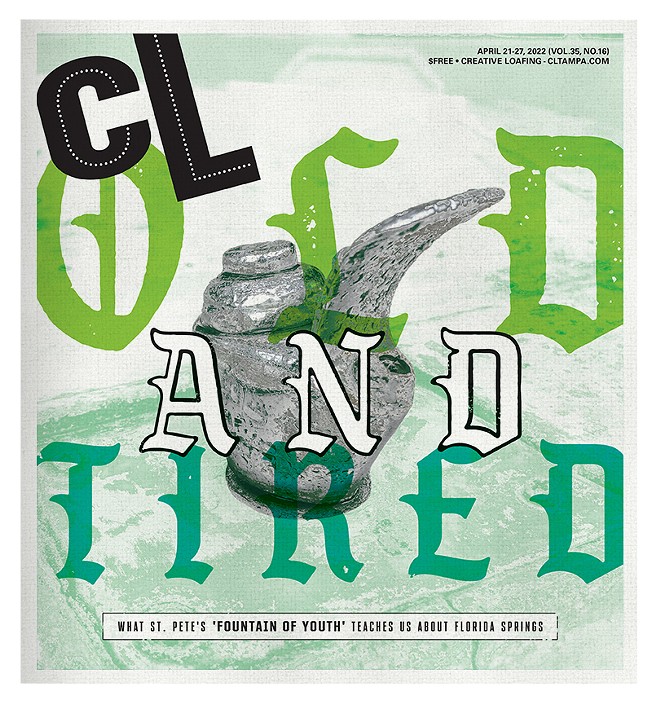

My journey is much shorter. After two or three drizzly blocks, I find myself in a brick-paved octagon surrounded by a low wall of beige cement, with a white, water-stained pedestal rising out of the center. The space is guarded by two growling lion masks that once splashed water into basins below. The “fountain” itself is a water-stained spigot, turned slightly askew, not unlike the one I remember from the water fountain outside my high school gym. Truthfully, I wouldn’t have known this place for The Fountain of Youth if it weren’t for the old-timey script scrawled across the marker facing the street—which I only noticed as I was leaving.

Old postcards of this place frame it very differently: there is lush tropical greenery and grinning tourists (also sometimes gagging tourists, because the magical water was apparently pretty skunky). A statue of Ponce de León once stood on the pedestal, but had to be removed after multiple defacings. While I was not prepared for the more austere version before me, I was aware that the fountain had scaled down over the years.

St. Pete’s own “discovery” occurred in 1901, when local philanthropist Edwin H. Tomlinson tapped a well of sulfurous groundwater at the base of a fishing pier he had built off 4th Avenue S. Visitors soon began flocking to this “fountain of youth” to taste the waters, reasoning, I suppose, that anything that smelled so medicinal must in fact be good for you. A few years later, one of these visitors (Dr. Jesse Conrad) returned to buy the pier and expand the site with facilities for bathing and drinking and an eye-catching sign. About the same time, another get-young-quick attraction had opened across the state in St. Augustine. Indeed, that Fountain of Youth, built on the grounds of an old Spanish mission, is still booming today, with tourists coming from far and wide to drink water from its spring out of little plastic cups—or, if they’re feeling classy, out of a blue wine bottle complete with cork.

Photo via Florida Memory

A 1934 postcard (Gulf Coast Card Co.) showing folks enjoying the waters. The card notes: "Thousands of gallons of Fountain of Youth water, said to have curative values for those suffering with rheumatism and neuritis, are carried away from the ever flowing well yearly in jars."

Of course, there’s not much proof to suggest that Ponce de León actually visited either of these sites, or the many others that now carry his name. (My personal favorite: De Leon Springs in Volusia County, an only-in-Florida blend of a former sugar plantation turned elephant water-skiing pond turned make-your-own pancakes restaurant—somehow also a state park.) In fact, prevailing wisdom has it that Ponce de León wasn’t even seeking the Fountain of Youth so much as, like other conquistadores, gold, land, and people to enslave.

Later writers who claimed he was seeking the Fountain were more likely throwing shade, suggesting that Ponce was either foolhardy (looking for something that obviously didn’t exist) or impotent (one of the things the Fountain was said to restore was your…um, personal vitality).

In the end, the water that Ponce de León—along with his navigator Antón de Alaminos—should probably be known for is not the Fountain, but the Gulf Stream, the powerful current that hugs Florida’s coast and pushes northward along the Atlantic seaboard. This flow would prove instrumental in the process of European colonization, powering, among other things, the infamous Triangle Trade in sugar, rum, and enslaved people.

But the myth of the Fountain of Youth stuck, and perhaps it’s no surprise. As Rick Kilby points out in his richly illustrated tour of Florida’s Fountain-related sites (“Finding the Fountain of Youth,” 2013), this story has taken on iconic power in promoting Florida to would-be visitors, even as Ponce de León—and celebrating colonial invasion in general—has fallen out of favor.

“For five centuries, the idea of Florida has been linked to the life-giving properties of its water, both real and mythic,” Kilby writes. This is perhaps especially true in St. Pete, where early boosters like Dr. W. C. Van Bibber were already promoting the city’s warm climate, salt breezes, and abundant sunshine as creating a “Health City” perfect for ailing snowbirds.

Photo via Florida Memory

A 1951 photograph showing visitors enjoying (sort of) the medicinal waters.

I wish I could say the same for myself. Standing in this tiny, forgotten spot, squeezed on both sides by the vast, currently empty parking lots of Al Lang Field and the Mahaffey Theater, it’s hard not to feel disappointed. Why? Because I failed to find a magical elixir to turn back the ravages of my nearly 40 years (or even just the last two)? Or maybe it was discovering a place that once bubbled with life now so deserted? Or maybe it’s a more profound concern, one that goes as deep as the aquifer itself.

Because, as the Fountain of Youth’s popularity illustrates, the story of water in Florida has, for so long, been a legend of ever-renewing abundance.

Our springs, our seas, and even the vast Floridan aquifer that waters so many of our cities and farms—all have been imagined as an endless wellspring that allows us to defy the ironclad rules of depletion and exhaustion. We are beginning to see the consequences of living in this fairytale: the Florida Springs Institute determined in 2018 that there has been a 32% reduction in average spring flows between 1950 and 2010, even as withdrawals for residential and agricultural use continue to climb. As National Geographic’s Jon Heggie puts it: “In Florida, the health of the aquifer is visible in its springs. With insufficient water to create high pressure, the flows stop, algae forms, and the springs’ clear waters become stagnant and brackish, and may even ultimately run dry.”

I’ve seen this anti-miracle for myself: after a formative Florida experience at the extraordinary first-magnitude Wakulla Springs in the late 1990s, I returned to share this special place with my partner in 2015. Nostalgic for the magical glass-bottomed boat tour I had taken as a kid, I was disappointed to learn the boats weren’t running. Thanks to run-off and reduced flow, the water just isn’t clear enough most of the time. I climbed the old dive tower to peer into the 200-foot wide entrance to the massive cave at the bottom of the basin, a ghostly place that still burned bright in my memory, littered with mammoth bones and peopled by hundreds of schooling fish. What I saw instead: a lone snorkeler trying to spot a manatee who was less than 15 feet away. His family was shouting instructions down into the pool: “On your left! Ten’o’clock!” they cried. No good; the water was too dim.

And while Tampa Bay’s urban springs are smaller than their giant cousins, their struggles are, in a way, even more spectacular. Paved over, piped away, polluted, or fouled by rising salt water, they are often the first casualties of development, indicators of our vexed relationship with the water we depend upon. Many of them could be restored, their flows regaining some of their lost power to feed the bay, provide habitat, and wow us with their extraordinary beauty. But this—along with saving the big springs up north—would require us to move beyond desiring eternal youth and expecting eternal plenty. As I stand alone, shivering in the cold drizzle, a vision comes to me: maybe we should transform this lonely place into a Fountain of Elders, a vantage point where we could keep a vigil over our life-giving bay. A shrine whose waters would magically inspire outpourings of thanks to the land that has provided us so much, and floods of respect for this beautiful, fragile, utterly unique place we now call Florida. the story of water in Florida has, for so long, been a legend of ever-renewing abundance.

Yeah, that’s it: Fountain of Elders! I think, pulling up my hood for the return pilgrimage to my car. That will look great on a postcard.