In 1973, when I wasn't even a year old, the U.S. started drilling for oil in Alaska, withdrew troops from Vietnam and passed the Endangered Species Act. It was also the last time anyone saw Florida panther kittens north of the Caloosahatchee River.

Until last month, when a biologist working with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission caught two kittens on camera in Highlands County — north of the Caloosahatchee.

Read that again, because in this age of Lake O discharges, the seemingly imminent disassemblage of the EPA, and the knowledge that, once we melt a bit more glacier with our greenhouse gasses, the CL Space in Ybor will have waterfront access, an almost-extinct species is making that sort of progress? Well, it's pretty damn fantastic.

Florida panther once roamed as far west as Louisiana, and as far north as Arkansas and South Carolina.

Human predation — in the form of shootings, development and car collisions — reduced that habitat to south of the Caloosahatchee River (think Fort Myers and south only), or about one-twentieth of what it used to be. When Ponce de Leon came to Florida in the early part of the 16th century, no doubt panther outnumbered people. From that point forward, though, humans brought the species to its knees.

But now we may be allowing it to rise again.

To get these first few tentative pawprints in the sand — or the swamp or forest — it's taken five decades and three government agencies.

"Life for a Florida panther is a mixed bag," Florida photographer, Carlton Ward, says. Last spring, the National Geographic Society gave him a grant so he could use his images to tell the Florida panther's story to the world.

"I'm trying to capture the essence of what it's like to be a Florida panther living in the Florida woods," he says. "I'm trying to find evocative imagery that can help people emotionally connect with a panther."

In 1832, hunters bringing in dead panthers received a bounty; in 1887, hunters received $5 per panther scalp. Combine that with Florida land getting clear cut and the panther's main food source — deer — going from 13 million to 1 million between 1850 and 1900, Florida panther numbered only 500 by 1900 — and, of the 27 subspecies of panther that once roamed the eastern part of the country, the Florida panther alone now peers out from the cabbage palms.

In 1950, Florida declared the Florida panther a game species, which allowed for hunting but also imposed bag limits. In 1958, the state listed it as an endangered species. In 1978, the state made killing a panther a felony. In 1992, biologists found less than 100 panthers in south Florida.

Today, FWC panther team leader Darrell Land says somewhere between 120 and 230 panthers exist (not counting, he says, kittens still dependent on their mothers). It may not seem like a huge jump, but at the low end, it's a 20 percent increase in population. At the high end? The population has more than doubled.

As those numbers increase, though, panthers need more room to roam.

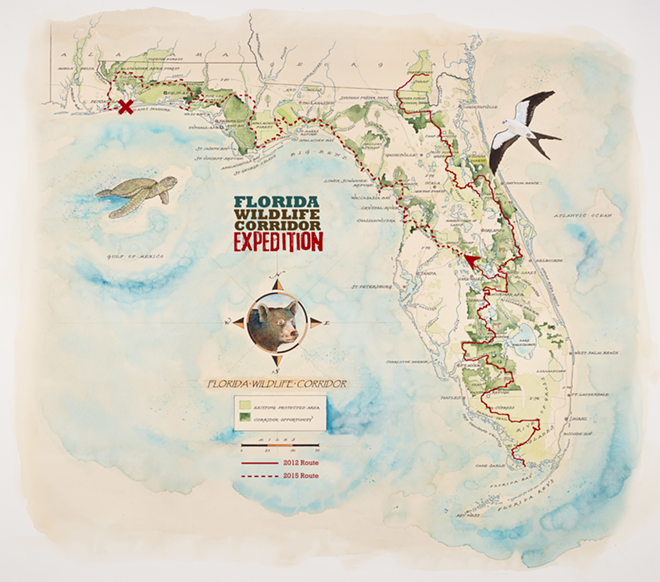

Ward's network of camera traps — six in all — catch panthers as they move between a blend of public and private land. Half of those camera traps live north of the Caloosahatchee River; he's set the other half south of the river. They sit on both public and private land.

While the cameras sit on both sides of the river — a river Lindsay Cross, the Florida Wildlife Corridor's Executive Director calls "the biggest barrier" to the panther expanding its habitat — only males would cross the Caloosahatchee.

"The male panthers were crossing — they would swim," Cross says. "The females had been only found south of the Caloosahatchee, which meant that males would also have to be in that same area to breed with females, so that was essentially limiting their functional habitat space to the area in south Florida."

If the population expands but the area doesn't, she says, it's not good for the panthers.

"The males need several hundred miles of habitat range to find adequate food, to find mates," she says. "Also, there's competition between them for dominance."

That's where the Florida Wildlife Corridor comes in.

Ward can tell the panther's story and FWC can protect the panthers so the cats have a story; the Florida Wildlife Corridor wants the cats to have more room to make more stories.

The notion of a wildlife corridor isn't new — biologists in Central America created a corridor so monkeys could cross from south America to north without coming out of the canopy — but in Florida, where Interstates and subdivisions wage constant war on wildlife, it's complex.

"Most of these panthers are using privately owned ranch land, and due to the human population growth," Cross says,"a lot of these areas could be developed into urban landscapes if they're not protected through appropriate mechanisms like conservation easements or land acquisition."

A conservation easement sounds more complex than it is: It limits the future development rights for a property. For example, if a rancher owns 1,000 acres of cattle ranch, he can get an easement that allows the ranch to always be a ranch — even if it changes ownership — but no matter what happens, no one can develop the land for a more intense use, like a shopping mall or a Sun City Center.

Since creating a conservation easement means the landowner gives up the higher profits he would get if he could sell the land to a strip mall developer, the conservation easement comes with a tax break: The difference in the value of the land with full development rights compared to current development rights. That easement, Cross says, "stays with the property forever."

Within the 16 million acres in the Florida Wildlife Corridor, over 2,000 acres of land have conservation easements and over 9 1/2 million acres have protection of some form (parks, preserves and other public lands). That's good news for panthers, because more room to roam means less competition, and less competition means less time fighting and more time making panther kittens.

"The greatest challenge to the Florida panther is access to habitat," Ward says. "For the Florida panther to be considered recovered from the endangered species list, there needs to be three times the number of panthers there are today, distributed across two different additional populations in different parts of Florida or the Southeast."

"This," he says "is where the Florida Wildlife Corridor and protecting a network of public and private and conservation lands throughout the Florida peninsula is really the answer for providing a path to recovery for the Florida panther, because without access to that habitat, the prospects of recovery become increasingly bleak."

That, Ward says, could be a grim reality.

"We lose 20 acres an hour to development," he says. "The land that is being lost to development is predominantly working agricultural land, cattle ranches, timberland, orange groves — all of which provide functional habitat for panthers and other wildlife."

Nevertheless, he says, it isn't all doom and gloom.

"This is the first time in my lifetime that there's been the opportunity for the breeding range to actually expand north of the Caloosahatchee River, and that is the first step toward establishing an additional breeding population and moving in a direction where the panther can recover into its former range throughout the Florida peninsula," he says. Telling the story of the Florida panther is another step.

"I am going deep into the story of the Florida panther, because the plight of the panther and the story of the panther embodies the story of wild Florida," he says. "I believe telling the panther's story is our best chance to emotionally connect the wildlife corridor and these wild places to a larger audience."

When I was in fourth grade, I cast my vote to make the Florida panther our state animal. At 8 years old, I thought they were cute (my mom's cat allergies made cats an impossibility, so this was as close as I thought I'd ever get to having a cat), and I knew they were endangered, but I didn't grasp the nuances of what that meant.

When I look at the numbers now — 35 years later — I get the nuances.

Two kittens, in the grand scheme of things, don't seem like a big deal. After all, we're only talking about two kittens.

I hope Ward succeeds in telling the Florida panther's story.

I hope the FWC continues to sell more panther license plates to help fund its efforts.

I hope the Florida Wildlife Corridor can convince more ranchers to get a conservation easement.

But, above all, I hope those kittens succeed.

Kitten steps, right?