Hope: Artwork by Aithan Shapira

Through July 19 at Florida Holocaust Museum, 55 Fifth St. S., St. Petersburg; 727-820-0100, flholocaustmuseum.org.

When Aithan Shapira was studying for a degree in printmaking at the Royal College of Art in London, he crossed the Thames River on foot nearly every day using the Hungerford Bridge. Often he would duck into an art museum along the way — the art-and-design fusing Victoria and Albert or the Tate Britain, where he walked on Friday afternoons to examine J. M. W. Turner’s light-filled landscape paintings after picking up a sandwich. But a less magnificent sight — a single, tattered red-and-white life preserver perched on one of the Hungerford’s piers, visible to pedestrians on the adjacent footbridge — also stuck with him.

A couple of years later, the image resurfaced in Shapira’s mind when he turned in his art to a subject inspired by his time away from the U.S. — hope. Hope as in Obama had just been elected (for the first time) and a new generation of citizens (the millennials, of whom Shapira, at 35, counts as one) was voicing its commitment to transparency and social justice. While Shapira was studying abroad, first in London, then in Australia, where he took on a Ph.D in art, hope seemed to have left America behind — or the other way around. Now it was back.

“I looked at that life ring and thought, there’s something about it that’s abandoned and no one can get to. Fast forward to when I was thinking what does hope look like — I thought of that ring,” Shapira recalled during a recent phone interview from his studio in Boston. “Hope was that abandoned life preserver.”

Fast forward to this summer and a solo exhibition titled Hope of Shapira’s prints, paintings and sculptures at the Florida Holocaust Museum in St. Petersburg. Across the 18 works he chose to make up the exhibition, Shapira incorporates and reiterates the life preserver as a visual motif, exploring the meaning of hope in all of its precariousness and resilience, its joy and pain. (The number 18 has spiritual resonance as the sum of the letters that make up chai, the Hebrew word for “life.”) One life ring perches in the center of a fox trap in a color still life; another is cast in gray concrete then shattered into dust. The works acquire an extra charge of resonance in a Holocaust museum — Shapira, who is Jewish, grew up in New Jersey and Jerusalem and counts close relatives among those lost to the genocide — but his project has broader goals.

One is exploring how, as an artist, to imbue a single symbol with powerful and varied meanings. During his stint in Australia, Shapira sought an answer to the question by living with an aboriginal community in the country’s Northern Territory. Watching members of the community paint with natural materials to preserve and transmit cultural stories — a model different from the West’s concept of art as an individual creative endeavor — stimulated his formal experiments. Though he stuck with oil painting, Shapira began incorporating Israeli earth and olive tree ash into his custom blended paints. The result is that some of his quiet, tree-filled landscapes — broken up by the presence of red life preservers — are painted with the substance of the very thing they represent, intensifying (at least in theory) the significance conveyed.

“It’s like a chef,” Shapira said. “If you’ve got good ingredients, it’s more likely that things will line up right. It doesn’t mean it’s going to be the greatest meal every time, but it gives me some meaning to start with.”

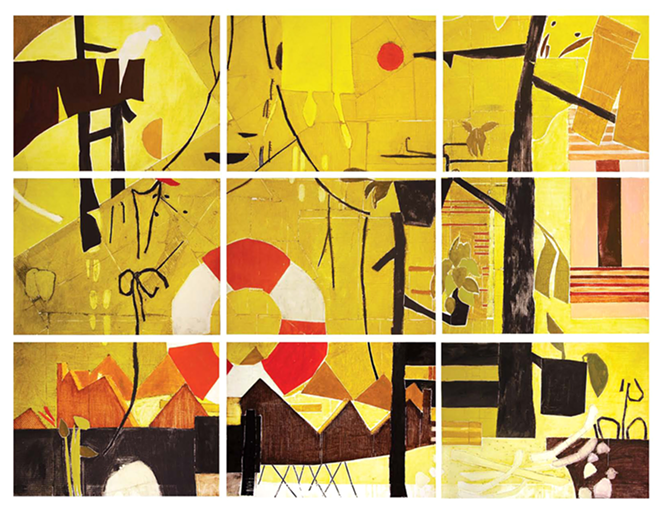

His prints, 8-foot by 10-foot collagraphs created from impressions of cardboard, are another experimentation. Shapira began making them in London, using the floor of his cramped studio as a work surface and cutting out shapes that, he recognized in retrospect, evoked the patterns for women’s coats that he saw as a kid hanging in his father’s factory.

But Shapira’s patterns layer up into still life studio scenes. If he’s lucky he can squeeze five or six prints out of one cardboard composition before what’s left is too flat to coat with ink and press. These are the strongest works in the show, balancing graphic simplicity and the earthy texture of cardboard with mysterious abstractions and the occasional hint of a figure. In addition to the two included in “Hope,” two can be seen at the Alfond Inn in Winter Park as part of the Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art owned by Rollins College.

Shapira might never have made the collagraphs if he could have spent more to work with traditional printmaking techniques as a student.

“What I couldn’t do was afford 60 pounds for a copper plate,” he remembers. “I’ve got access to presses given to the queen in the 1800s, but I can’t afford the metal to send through it.”

Shapira’s sculptures extend the show into another dimension, though one that could have used some paring down. (More than half of the works on view incorporate concrete rings.) But even in excess, the ghostly gray circles are poetic, invoking the poignancy of hope as a phenomenon at once strong and fragile, buoyant and burdensome. Perhaps most importantly, in the context of his art hope is something that is made. Settled now in Boston and expecting a child with his wife, Shapira reports appreciating new and more personal dimensions of hope. The sense of potential recalls the message with which he inherited a pair of homelands, Israel and the U.S., from his grandfather and father, respectively.

“It’s up to you what you’re going to do with it,” Shapira said.