Too long a sacrifice

Can make a stone of the heart.

O when may it suffice?

—from Easter 1916, by William Butler Yeats

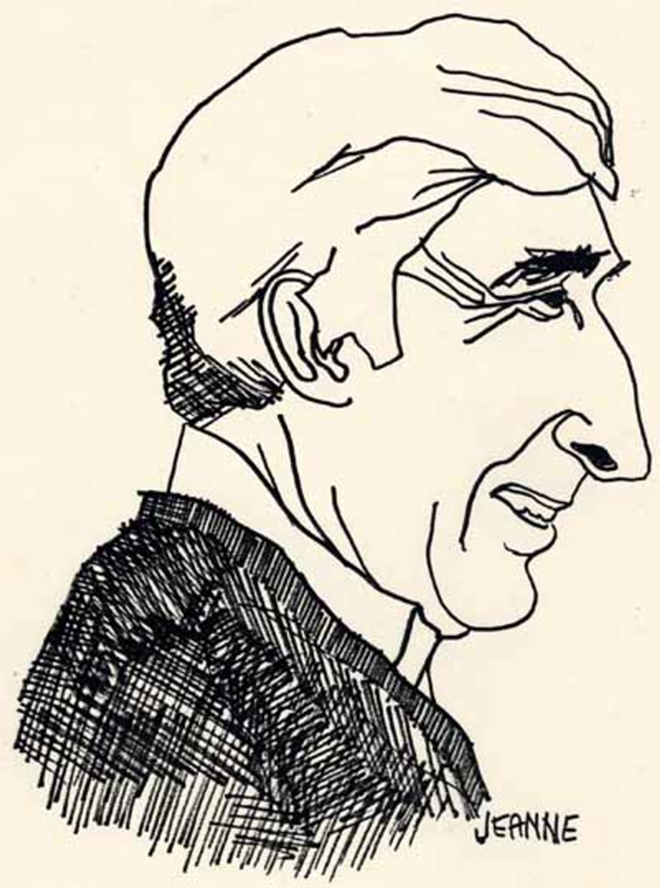

John Updike didn't quite make his 77th birthday, which would have been this month (March 18). But apparently he met every other deadline he was up against, churning out not just novels but wide-ranging essays, sly poems and world-class short stories, puritanical in his work ethic and hedonistic in his floral descriptions of sex ("Sex is like money; only too much is enough," says Piet Hanema in Couples [1968].) Many critics, wilting after page after page of elegantly scripted genitalia and their exertions, cried the equivalent of "Hey, enough already!" — but Updike had captured something real about America: our childlike greed for sensation, both romantic and self-indulgent, that led to an entire country living a dream on credit.

He was certainly, on one level, an urban intellectual, publishing throughout his life in The New Yorker. But he came from a small-town family (his father a high school teacher, memorialized in The Centaur); Updike told an interviewer that his writing tended to point "not toward New York but toward a vague spot a little to the east of Kansas."

Although he created occasional sophisticated alter egos — primarily the writer Henry Bech — Updike's main spokesman was Harry "Rabbit" Angstrom. The four alliterative Rabbit books — Rabbit, Run (1960), Rabbit Redux (1971), Rabbit Is Rich (1981) and Rabbit At Rest (1990), plus the novella Rabbit Remembered (2001) — comprise our most comprehensive and readable summary of America's emotions at the end of the 20th century. Rabbit was a likable (because vulnerable and hopeful) loser, a pro-war conservative, a racial bigot who was willing, uneasily, to listen. Through Rabbit, Updike was able to be painfully honest about sex, money and race (and their connections), without the filter of theory. Rabbit just experiences these "subjects," and reacts to them. Our other great writers on these problems — J.D. Salinger, Erica Jong, Philip Roth, for example — gave us the perspective of sensitive educated kids and grown-ups, but Rabbit's a not-too-bright jock whose life peaked as a high school basketball player.

I was re-reading Updike when I also read that Eric Holder — our first black attorney general — had accused Americans of being a "nation of cowards," afraid of confronting the racial issues that ravage our country. Obviously there's truth in that accusation, because race (along with sex and money) is such an abrasive subject. Most of our conversations, like most of our neighborhoods and churches, remain segregated. Everyone likes to be comfortable, and race is our most uncomfortable subject (the test is, you can easily joke about sex and money, but not race).

But Updike has faced this issue, along with other writers, including two with recent local connections: black playwright August Wilson (1945-2005) and Dennis Lehane (b. 1965). Wilson's Pittsburgh cycle of ten plays is being produced by St. Petersburg's American Stage, most recently King Hedley II; and Lehane (whose novels, including last year's The Given Day, form a sort of Boston cycle) is writer-in-residence at Eckerd College.

These writers have produced three of the most vivid black characters in our literature: Wilson's King Hedley, Lehane's Luther Laurence in The Given Day, and Updike's "Skeeter" Farnsworth in Rabbit Redux. Despite being sympathetically portrayed, all three are criminals, at least in the eyes of the law. Class and prejudice push them that way, no matter how they twist. Only Lehane's Laurence escapes, at least temporarily, in a riveting finale, where Laurence's nobility, intelligence and pitching arm come together to make him a larger-than-life hero. Wilson's King Hedley ("King" is his real name) is a lower-class Pittsburghian; and he, too, is given epic dignity as he tries to raise enough money to enter the middle-class world — but events, caused by both society and his own bad choices, doom him to tragedy, like an American Othello. Updike's Skeeter is the least noble, though the smartest, of the three; and is the most realistically drawn. He speaks searingly about race in America, but the just-divorced Rabbit is caught up in his own suffering, and can't hear the truth that the flawed, drug-dealing Skeeter preaches. Still, he does learn, slowly, in his own way.

Updike reversed the Yeatsian idea that suffering just hardens the oppressed classes (the Irish, the blacks, the Jews) for so long that their hearts have turned to stone. Or he had a more complicated idea of oppression, sympathizing with "average" guys like Rabbit, who — like many Americans — is overstressed, overdrawn, overweight and undereducated. Rabbit's a white American striving to be upwardly mobile, and has too many problems of his own to feel guilty about others. Hearts are hardened on both sides.

In any case, to contradict Holder somewhat, because these three writers have directly addressed the race problem, so have their audiences. One can't say they're optimistic, but in recognizing our common humanity, they present the possibility of reconciliation. Updike, in particular, believed in the basic innocence of our country, and people in general, using Rabbit as the example. "America is a vast conspiracy to make you happy," Updike said. If Rabbit can learn, against all odds, to accept our differences, so can America. In this past election, we made a start.

—Peter Meinke (www.petermeinke.com) will be reading with other poets at the Brandon Regional Library at 2 p.m. Sunday, April 5. John Updike once wrote to the editor of Light Year '87 — a collection of humorous poetry, including a poem of his own — saying how much he enjoyed the illustrations by Jeanne Meinke. Requiescat in pace.