Tableau and Transformation: Photography from the Permanent Collection occupies two galleries in the Tampa Museum of Art. The exhibition organizes photography focused on the artists’ own transformation within the genre of the tableau: the staged arrangement of props, backdrops, and other accoutrements that are then photographed.

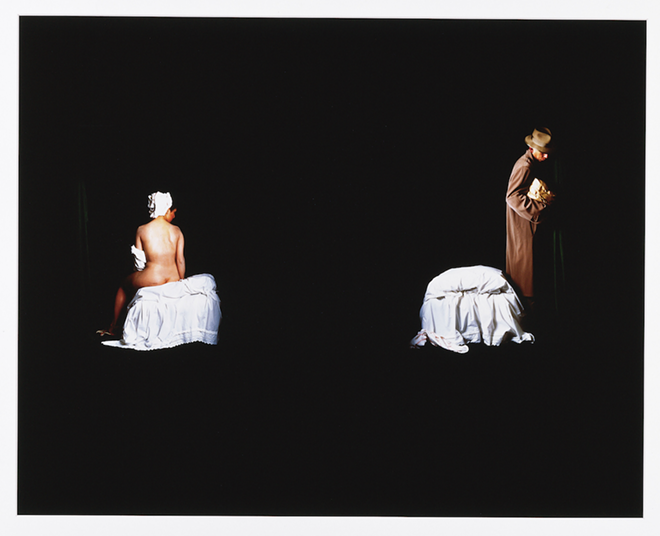

The images in the first gallery are largely expected. Domestic animals given the couture treatment of Harper’s Bazaar in elegantly shot works by William Wegman, and carefully articulated photographs of nude woman in domestic spaces with an absurd array of objects in avant-garde “fictions” by Les Krims. An engaging piece by Stephen Frailey, called “Untitled #10” (1987), depicts two people facing an enlarged image of a woman with one eye exposed. Like most of the work displayed, the background is so densely black that it becomes a mirror, reflecting the viewer looking at it. It’s cleverly self-referential, even if a little cheesy. The one eye exposed is funny, too, recalling the one eye that must be closed when looking through a traditional camera lens.

Though most of the subject matter is predictable, the rendering is surprisingly diverse. Cindy Skoglund’s radioactive color palette kick-starts a visual sugar rush against the mostly monochromatic works in the gallery. John Baldessari’s massive “Waterline” (1986) combines six images of water-related activities into one print through Baldesarri’s signature cheeky style. The piece conjures photography’s ability to capture motion but also the medium’s amphibious life cycle, requiring certain times of being wet and malleable during its making, like in a darkroom, to fully mature. “Waterfall” (1983) by James Casebere doesn’t literally depict water, but the gorgeous cascading of light in Casebere’s synthetic mise en scène flutters with the natural grace of water.

A triptych by Laurie Simmons presents the bottom half of dolls combined with new top halves: a hot dog, a glove, and a dollhouse. Titled “Food, Clothing, Shelter” (1996), Simmons’ noir lighting ignites a wary mood. Here, the dolls bear the clear, symbolic weight of whatever object is on their shoulders. The hot dog indicates substance for children but also satisfying other appetites for the husband. A glove brings up ideas of fashion, but also the psychology of the gentle hand of the mother versus the firm hand of the father. A house could symbolize the pressure of maintaining a home thrust upon 1950s American women (an era that Simmons clearly scrutinizes). Deeper still, the house is a stand-in for keeping it all together: the pressure of looking cool, calm, collected, and chic while also negotiating between conflicting demands that are impossible to reconcile. Though a little heavy-handed, Simmons’ work still has unexpected richness that can be squeezed out.

The dolls don’t stop there. In the second gallery, things get much weirder. Morton Bartlett’s “Girl with Fur Collar” (c. 1955/2006) greets visitors with the gleaming smile of a girl frozen in reverie. From afar, the traditional composition, naturalistic lighting, and stylish clothing lures the viewer into believing it’s a standard portrait. Upon closer inspection, this figure is a carefully constructed doll wielding a convincingly human expression. The soft squeeze of her eyelids wincing, her freshly slick lips, her head admiringly tilted upwards as if attuned to some delicious, invisible signal: All contribute to a shockingly accurate depiction of a real person with a lush inner life. The idiosyncratic patience and vision required by Bartlett and the other artists exhibited bears consideration. “Girl with Fur Collar” is a slow burn that’s both acutely distressing and charming.

Perhaps the largest piece in the show is Cindy Sherman’s menacing “Untitled (#141)” (1986). Presented beside the much smaller but equally bizarre “Untitled (Pig Woman)” (1986), “Untitled (#141)” presents a totemic, otherworldly marauder/military leader, fists and teeth clenched with conviction. Sherman is famous for her histrionic images, and though we know it’s Sherman herself because she poses for all her photographs, the figure presented is of almost indeterminate gender and age. Sporting an eyepatch (the one eye appears again), leather pants, flannel coat, and grimacing teeth, the figure stands firm like a sentinel over a desolate, maybe alien landscape. The distinct clothing and atmosphere bring to mind the sci-fi/action movies of the late 1990s like The Matrix, Blade, and The Fifth Element; maybe even Missy Elliott music videos. The fact that this image predates all those examples is more impressive still.

Despite the palpable dread and cumulative weirdness of this photograph, the strangest moment is the flicker of the figure’s lower belly exposed by a mellow glow. It’s a tender moment made especially unusual within the rest of the image. “Untitled (#141)” is compelling because it reveals very little of its tableau construction, even though we know it to be there. As a result, the viewer can’t isolate the process of making as they could in Laurie Anderson’s work or John Baldessari’s. Instead, they’re left almost weightless; floating through the surreal mood without much evidence of its construction to hold onto.

The exhibition is weakest when it relies on flimsy content and discards a more enthusiastic attention to form and style. William Wegman’s images of Weimaraner dogs, for example, are probably richer to him as their owner than to the general public as the viewer in a museum. Even in his more nuanced images, like “Untitled (Fay Draped in Red)” (1988), the saccharine backstory provided by the wall text distracts from the gorgeous color tones and uncanny forms. Both the color and the form elicit ideas of the sacred and the unsettling, which is richer territory than the personal history of a pet.

Similarly, “Self Portrait” (1969-73) by Arnulf Rainer relies too heavily on what it attempts to convey and half-heartedly considers how to convey it. A photograph of a pained, male figure covered in swathes of paint, Rainer attempts to seduce us with the visualization of his inner turmoil, the swirling paint strokes accentuating or even inflicting the pain made visible by the figure’s expression. This “overpainting” technique, however, is clearly perfunctory; the angsty aspirations of the work camouflaging its lackluster presentation.

Tableau and Transformation presents an eclectic group of artworks focused on how artists stage photographs. Essentially, it’s a show about the act of arrangement: how artists position both found and handmade objects, in coordination with precise lighting, to specific ends. These ends could be the illusion of real space, the creation of an entirely new, peculiar space, or to expose the structures that frame viewing art in the first place. The exhibition successfully presents different types of work within a relatively niche and rigid genre, but they’re probably a little too well-behaved.

Keep up with Tampa Bay arts, culture, food, music and more — sign up for our newsletters.