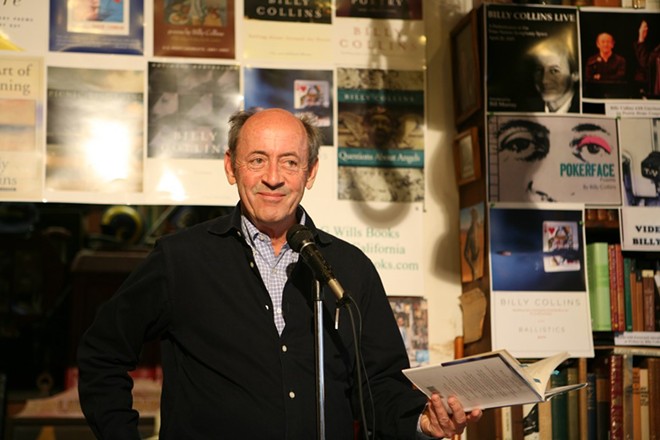

In November, the writer and Winter Park resident released his new book, “Musical Tables,” via Penguin Random House. The work is one of his longest books—I counted 129 poems—and in a lot of ways, also one of his shortest. There are poems that are like a single line or couplet, and it’s a wonder how Collins, 81, ended up going in this direction.

“I think I really was drawn to small poems early on,” Collins told Creative Loafing Tampa Bay. “When I get a book of new poems, I often just flip through and see if I can find short ones. And nursery rhymes are short. But I think when I was in high school, I discovered haiku because the beat movement was going on then.”

As he sifted through journals a year or so ago, Collins found a trail. So he went back into notebooks and easily gathered 100 poems and started writing more, in a very concentrated way, thinking he would end up with a novelty book called, “100 Small Poems.” But his editor had a different idea. “He immediately said, ‘This is not a novelty. This is not a curiosity. This is just our next book,’” Collins added.

Read more of our Q&A below.

When you say you’ve gone back to journals, does that mean some of these poems are much older?

I’d say most of them are within the past five or seven years, so probably a few that are that are slightly older but you can’t really tell the difference because I haven’t developed much, or any, as a short poem writer, they all seem to be kind of doings something of the same thing. I’ll give you an example:

3:00AM

Only my hand

is asleep,

but it’s a start.

Here’s another:

Motel Parking Lot

Saying goodbye is so sad,

I don’t even bother

to turn around to see

what it was you just threw at me.

There’s no time for things like landscape or meditation or memories and that kind of thing. And there’s certainly no room for suspense. But there is room for what I would call “torque” that involves a twisting and turning like a wrench. So often, the torque of the twist involves some interplay between literal and figurative…it can be taking a cliché and twisting it into a new shape, maybe taking it literarily.

To that end, many of your poems have this sense of humor that comes from twisting those clichés and expanding them. How does that humorous torque work for small poems? Does it feel more like making a joke?

It’s a very distinct feeling. I think you’ve got to get in the mood for it or be on the lookout…if you’re watching television or reading and you come across something you think can be twisted… But, often the little poems arrive fully formed. And there’s very little what you call “a compositional process,” very minimal revision. And that’s kind of the thrill of them—that they arrive with immediacy. They just occur. [But] just because it’s a short poem, it still has the possibility of a certain poignancy…I think the best poems there’s playfulness and there’s seriousness. There can be a little stab, a little tension.

With a title like “Musical Tables,” I do have to ask you about musical influences in your work. I know you’re a lover of jazz and in your longer poems, there’s definitely a musicality to it. What sort of musicality do small poems have?

I think if you’ve got a really short one, it’s almost like a chord. The effect of the poem is so sudden that it’s not so much a number of notes as a certain chord that leaves you with some kind of feeling. You really reduce the musical possibilities of a poem when you get rid of the long line, or the pentameter line.

If you had to pick an instrument for the chord of small poems, what would it be?

I guess maybe the French horn or the trumpet. Something with one or two notes and has a sharpness. But again, music tends to be continuous and builds upon itself. In small poems, one sacrifices musicality and lyricism, one sacrifices the development of persona, any kind of conversational intimacy you might have had with the reader if you were writing a somewhat longer poem. But what you gain is a kind of radical example of poetry’s long honored and praised ability to say important things in very small spaces…to push strong emotion into a poem of 140 syllables (which is basically a perfect sonnet) but here it’s more like pushing some kind of meaning or emotion into a handful of syllables.

Do you think that small poems are able to use silence more just because there’s so much literary white space surrounding them?

Yeah, that’s spot on. In "Musical Tables," each little poem has its own page, so there’s a great deal of silence surrounding it. I think the key difference between poetry and prose is that prose fills a page line by line [then] onto the next page. Poetry occupies a discreet place on the page, a little area where it takes place and I think of the blank space around any poem as being silence, so I like to say that poetry (or a poem) is the displacement of silence.

You’re not what I’d call a reactionary poet, your work isn’t necessarily influenced by outside events (with a very notable exception) but the past two years changed everything. Has the pandemic affected your writing?

Well, the effect of the pandemic on my writing was that it brought almost to a standstill. You would think that in a pandemic, a lockdown, that creative types would have more room to paint or write or compose music. For me, that was not the offering. The pandemic didn’t offer more time; it took time and just turned it into a totally different shape. And it did this essentially by eliminating the future, right? I mean, during lockdown, ‘What are you doing next week?’ You aren’t doing anything. So I didn’t get a lot of writing done.

Have you found your want back to writing as we’ve shifted out [of the pandemic] or has it gone a different way?

Well, I’m just writing fewer poems and it’s just that time in my life where I’m gonna write less and less. I mean [my editor] thought this as another interesting stage in my literary development, where, as I suspect, it really was the beginning of the end and that I would just, you know, just continue to write shorter and shorter poems, and then one word poems, and then just nothing. Just flatline.

I hope not!

(chuckles) We’ll see. I don’t know, maybe I’ll just take up water coloring or collage or something, just hang up the poetry. Maybe your not supposed to do this forever.

Tim O’Brien became a stage magician.

Did he really? That’s an amazing ability to go into something totally different. I’m still thinking about the watercolors. Just put a blanket over my knees and set me up by a lake with some watercolors and don’t forget I’m there.

Come and pick me up before it gets dark and cold.