It happened in 1990, and it had to have taken place backstage at the grand ballroom inside of the since-closed Embers Hotel in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. James Suggs was 10 years old, and a family member had driven him from Harrisburg to see the then 29-year-old Wynton Marsalis. During the set break, someone snuck Suggs behind the scene to meet the jazz legend, who pretty much opened his arms in inviting the youngster with a mild interest in trumpet to have a chat.

“He was hanging with another kid who was a little older than me, and that kid had braces. Marsalis was basically saying, ‘I’m sorry, I’ve never had braces, I don’t know what to tell you.’ The kid left, and it was just me and him,” Suggs, 39, told CL as he checked in from a gig at the Sarasota Jazz Festival. Marsalis asked Suggs if he played the trumpet.

“Yes,” Suggs replied. Marsalis countered with, “Do you practice?”

Suggs responded in the affirmative, but the farce was up. Marsalis gave the young trumpet player a playful, skeptical side eye and invited Suggs to sit at the piano to explain why everyone should learn to compose at the keys. Marsalis went into an in-depth, impromptu one-on-one and threw everything at Suggs. He even put the kid’s hand on his belly so that could feel what proper breathing was like.

“His stomach was was rock hard when he was taking a breath,” Suggs recalled. And then Marsalis handed his $10,000 Monette horn to the kid and said, “Play something for me.”

“I was so nervous, all I could play was a C-major scale, and he gave me lessons about that,” Suggs said. A band member had to break it up to drag Marsalis back onstage, but the deed was done. “That transformed me. After that concert, I was set on becoming a jazz trumpet player.”

Suggs even wrote Marsalis a thank you letter and sent it to the address on the back of a recording by the jazz giant.

“I don’t know if he got it,” Suggs — who went on to study at Youngstown State, play cruise ships and gig for years in Argentina — explained. Marsalis probably gets lots of mail like that, and he may not have heard back from the icon, but the world at large is about ready to hear from Suggs some 30 years later. When CL reached the St. Petersburg-based Suggs, he was fresh off of a gig at the Newport Beach Jazz Festival where he performed with tenor saxophonist Houston Person.

Person, 84, has recorded nearly 100 albums as a bandleader and collaborated with the likes of hard-bop pianist Cedar Walton, fellow tenor sax player Eddie Harris and alto player Lanny Morgan. He has credits on works by the Isley Brothers and Santana. Pop and rap groups Def Squad, Dream and Kero One have even sampled Houston’s 1978 song “Pretty Please.” On Saturday, Person will be in St. Petersburg to join Suggs for a release party celebrating the trumpeter’s debut album.

Produced by Person himself and released in late 2018, You’re Gonna Hear From Me features three Suggs originals (“My Baby Kinda Sweet,” “The Ripple,” “But Oh, What Love”) and nine jazz standards like “Laura,” “The Night We Called It a Day” and “It Shouldn’t Happen To A Dream.” The album was recorded in classic Person fashion (old-school, two takes max) at Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey where Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Ornette Coleman and scores of others recorded. At one point in the process, Person — whose mind was always on sequencing for the tracks — needed to move his saxophone case. He asked studio assistant and wife of founder Don Sickler if he could place it in one of the old chairs.

“That’s fine, that’s what Coltrane used to do,” she told him. Suggs said that Van Gelder is the kind of studio where the wood has its own special smell. Person had the idea for Suggs to record the album’s title and closing track solo.

“That was the moment I realized how magical that place was. Just playing one note by myself in that room,” Suggs said. “The reverb, and the way the wood makes the trumpet sound was just incredible.”

Suggs will impart some of that energy to his fans this weekend, and he’ll do it with memories of his journey to this moment somewhere in the back of his mind. At one point in his career — before Argentina and gigs with Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey — Suggs was playing in ensembles alongside Sean Jones (now the jazz chairman at the Peabody Institute Conservatory of Johns Hopkins University). Suggs’ old Youngstown teacher, the late and great Tony Leonardi, used to show him tough love by telling him that he was now competing with the likes of Jones, Roy Hargrove, Nicholas Payton and Marsalis. At times it was frustrating, but Suggs persevered. After Argentina, Suggs moved closer to his sister to study and teach at the University of South Florida. St. Petersburg’s open and appreciative jazz scene drew him in. It’s where guitarist Nate Najar introduced him to bassist John Lamb and the late trombonist Buster Cooper.

“That right there is enough to be like, ‘OK, wait a minute. This is a different kind of place,’” Suggs said. “And it just kept happening. Not just with people I’ve been listening to for years, but with great, young musicians. There’s a vibrant scene and culture. That you can’t find in many places.”

St. Petersburg is home, and it's where Suggs has been able to flourish and develop his playing, which some have described as unpredictable at times.

“I know it’s a compliment, but it’s strange for me to hear. Obviously, coming from my own brain, it’s predictable. I’m playing what I’m hearing,” Suggs said, explaining that his deep dives into Miles and Louis Armstrong, combined with a tendency to play blues-oriented sounds, probably creates that unpredictable feeling for listeners.

“I get annoyed with myself sometimes,” Suggs said, “because I think it’s too predictable.”

Things appear to be on the up and up for Suggs. He’ll hopefully be a prized local jazz export for years to come; he and Person have even saved a few songs for the next album. We don’t know where Suggs’ exact path leads, but we can definitely hear his song loud and clear.

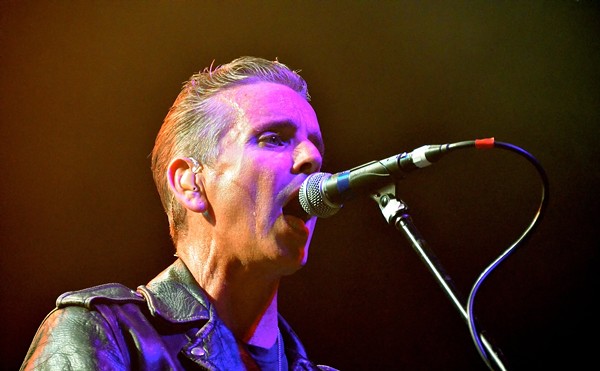

James Suggsw/Houston Person/John O’Leary/Alejandro Arenas/Mark Feinman, Sat. March 16, 8 p.m. $23-$25. Side Door Cabaret at The Palladium Theater, 253 5th Ave. N., St. Petersburg. mypalladium.org.

Read excerpts from our Q&A below. Follow @CL_music on Twitter to get the most up-to-date music news. Subscribe to our newsletter, too. Listen to 'You're Gonna Hear From Me' on Spotify, but also consider supporting Suggs at the show since Spotify is a dickhead that doesn't seem to want to pay artists their fair share.

Hey, James. Thanks for your time today. Are you in between classes right now?

I'm in Sarasota for the jazz festival. Houston and I were supposed to play a song together, but it didn't get to happen, they kept moving things around, but we got to hang a lot.

Could we talk about he approach you brought to the album and how Person, along with this dream band — Lafayette Harris on piano, Peter Washington on bass and Lewis Nash on drums — and how you were able to execute it?

We recorded in New Jersey, and the day before we went to New York City to rehearse. That's where I met the guys. We just went over the tunes, it took about two hours to meet everyone and go over the layout. The next day we all met up in the studio, and it's an amazing, legendary studio. Lafayette, Lewis and Peter were all in those little cabinets, so we could see each other, but we're all separated. Houston and I were together, side by side, recording.

Talking to people who really know Houston Person well, after the fact, they're like, "Oh you did classic Houston recording." Now I realize what that is. It's old-school. Everything is quick, and you're not gonna do three takes of a tune because by the time you get a third take you've lost the magic. So it's all about shooting for that first take, and if that doesn't work, then go fo the second. You're flying through the tunes, and in his mind, while we're recording, he was thinking about the order that they would be placed on the album.

So he sequenced it.

Yeah. So by the time he and I went to mastering the next day, it was just he and I, and the engineer. He had it all figured out, and it was perfect. They layout was perfect. I probably would've come up with a different order of tunes, and it wouldn't be as good. That just goes to show how experienced he is, how many times he's done this — he just knows what to do.

There was actually a tune called "Pretty Please," when I was researching him and his music, I found this tune from the early-'70s. It's a funky tune. I transcribed all the parts, and he was excited about it. He said that some rappers had sampled it, too. He was excited about recording, but right in the middle of the session he said, 'Man, I don't think we can do that tune," and I was like, "Why?" He was like, "I'm just not feeling it. I don't think it's a part of this album. Let's save it for the next one."

So he's always thinking about every little detail and every moment of the process.

You've been in many collaborative situations. You've taken guidance from so many different people, musicians and non-musicians. Was there any fear about handing all of this over?

I was afraid for other things. I was just really nervous. Like, now was the chance to prove yourself. After all these years of working hard, getting this opportunity, I didn't want to mess it up. I didn't want to be the slacker on the session day. Those guys are pros. They do this every day. They're going to sound amazing no matter what. It was hard to just jump into that situation.

And how'd you get linked up with Houston anyway?

Houston and I met a year ago at the Sarasota Jazz Festival. That's when we started to communicate by email and phone call about tunes we wanted to do. We'd go back and forth. I'd say, "I love this tune," and he'd say, "Nah, everyone plays that tune, so there's a long back and forth. And little by little we started to narrow the list down.

We were next door to each other at the hotel in Jersey, and he'd call me, and he'd say, "Hey, man, come over and let's talk about tunes." He'd have this big stack of tunes, and this was the day before, but he'd be pulling out more tunes, saying, "What about this? This one might work." I got to a point where I realized that I just had to trust him. If it wasn't going to work, then I had to be the "yes" man, and I was completely fine with it because it worked out.

What studios did you use?

Rehearsal studio was Second Floor Music, owned by Don Sickler. Recording was at Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. Rudy Van Gelder started recording in his parents' apartment, and in '59 he moved it to that same building that I recorded in. If you Google all the recordings that have been recorded since '59 it's just mind blowing.

So you're catching vibes in that room.

I totally did. You walk in, and you can smell the wood, and you walk into another time period. The chairs, some of the recording equipment, makes you realize you're in another era. Maureen Sickler, was there, and at one point Houston asked, "Hey is it OK if I put my saxophone case down on this chair?," and she said, "That's fine, that what Coltrane used to do." Maureen had so many stories. Random stuff. Lee Morgan, Duke Ellington, Ornette Coleman.

The last track and the title track from the album. It was Houston's idea for me to play that solo. That was the moment I realized how magical that place was. Just playing one note by myself in that room. The reverb, and the way the wood makes the trumpet sound was just incredible.

You started playing at nine thanks to some inspiration from a best friend. That friend quit band, but you continued and met Wynton Marsalis at age 10. You got a damn lesson during a set break, he started you on piano and also let you literally feel how he breathes. Could you talk about the thoughts in your head as your hand is on his stomach?

I remember every second of it. It's crazy. Like you said, that transformed me. After that concert, I was set on becoming a jazz trumpet player. I wrote him a thank you letter. I found the address on a recording I had, I don't even know if he got it. I remember walking in, and he was hanging with another kid who was a little older than me, and he had braces. Marsalis was basically saying, "I'm sorry, I've never had braces, I don't know what to tell you." The kid left, and it was just me and him, so I was like, "Oh, wow."

He called me over, and said, "Do you play the trumpet?," and I said, "Yeah," and he said, "Do you practice?," and I said, "Yeah." He kind of side-looked at me, like, "Come on kid, I know you're lying."

Then he went into this really in-depth one-on-one. He really only had about 15 minutes before he had to start again. He was throwing everything at me. I put my hand on his stomach and it was rock hard when he was taking a breath. He handed me fis $10,000 Monette trumpet, and said, "Play something for me." I was so nervous, all I could play was a C-major scale, and he gave me lessons about that. He talked about breathing and then sat down at the piano, played something for me, and said, "Everyone needs to learn how to play the piano."

He was just so into giving me all of the information that he could. A band member had to come in, kind of broke us up, and said, "Hey, we gotta get back onstage, man." He was so willing to give me all of his information for as long as he could.

That's crazy.

Yeah, and I was 10 years old.

So that was 1990? Do you remember where the gig was?

I was 10, and I was living in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania with my family, so it was kind of a dinner theater place.

You’ve talked about your live, and how you had good options. You've listened to people’s advice, the world, or whatever outside you believe in. You've let that guide you, and you've been fortunate to make a lot of good decisions. Have you ever made bad choices in your career?

Yeah, I think so, but I don't like to dwell on regret. Something I occasionally think about. I don't know if you're familiar with Sean Jones — he's a pretty famous jazz musician today. He's played with Wynton Marsalis at Lincoln Center. Marcus Miller, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, and now he's the director at the Peabody in Baltimore. We went to Youngstown State together, and he was a couple years ahead of me and just tearing the scene up. It was just a matter of time before he blew up, which is actually what he ended up doing around that time. He graduated, and went on to Rutgers where he got his Master's. That was pretty much the link to breaking into that New York scene.

I remember he told me, soon after, "Man I can get you hooked up with Rutgers. You can go there, and you can study with my professor, and it'll change your career," and I told him, "No." I said, "Man, I don't think that's what I want to do." I ended up doing cruise ships, and eventually moving to Argentina, and I always think, "What if I would've done that? Would that have made me a big star, or whatever?"

But if you dwell on the past or the what-ifs, then it's just kind of meaningless. I always think that we make decision, and things happen for a reason. We have to take them for what they are, and appreciate them.

You talk about being a gopher during your time at Youngstown — you almost dropped out because of being frustrated about your progress on trumpet, you’ve said you felt like you were drowning. Was watching Sean part of that feeling?

Of course. Nowadays it's kind of a joke, but back then he was two classes ahead of me, and he was still playing in ensembles as this monster player, and I had to compete with him. We were good friends, and he would have me sit in with him at shows, but I remember a professor telling me, "You've got to start taking this seriously. Now you're competing against Sean Jones, you're competing against Roy Hargrove, Wynton Marsalis and Nicholas Payton."

That was kind of a big blow. I wanted to hear, "Nah, you'll be fine, keep studying and eventually you'll have to compete with those guys." So there was that realization with Sean in the next room, or the same room. I'm far from him as far as talent.

Who was that? Was it Jack Schantz or Scott Johnson?

Jack Schantz was my private jazz teacher starting in high school and continuing through college. He was the one that really got me started on jazz theory and harmonic movement. He was fun and laid back but would make me feel bad if I was slacking. He was the first jazz musician that I saw going from university to university (like four) to teach lessons and ensembles, and playing professionally, and supporting his wife and daughter. An inspiration.

Scott Johnston was at that time the principal trumpet in the Akron and Canton symphony orchestras. My parents also wanted me to study with the best classical/technical teacher around the area, not just jazz. I remember I had to audition in order to get lessons from him. I passed the audition and would study with him weekly. He was a stickler for sound and rhythm. He looked out for me, like getting my tuition waived for the University of Akron Brass Camp, or getting me into a Doc Severinsen or Byron Stripling or Marcus Belgrave pops concert and introducing me to all of them, as his talented student with a bright future.

Do you play anything besides the MBX 3 Heritage Bb trumpet?

I am officially an Artist with B&S. And yes, that is the only trumpet I play. I also play a Cuesnon flugelhorn from the 1960s.

So who was the professor at Youngstown?

That professor was Tony Leonardi, he was the head of the jazz program. He made it what it is today. It's a small school, but he single handedly built it into a really strong jazz program. He was a tough, old-school, Italian guy. He played the bass. He would berate you, let you have it. Tough love. He had a big heart, but the old-school way of letting you know it. Reality checks. He'd say, "You think you're sounding good and getting comfortable with your playing, but keep in mind that you're competing against these cats."

I know you don't want to dwell in negative stuff, and I don't know if this is a negative question, but how often do you still get that drowning feeling, or even a plateauing feeling these days? How do you persevere through that?

Fortunately, I haven't had that plateau feeling in a while. That happened while I was in Argentina, and it drove me crazy. It's weird to say, but I was too comfortable as far as my career. I was playing and touring with a famous Argentine band, making good money and living the dream, but my playing plateaued, and it was the most frustrating thing ever.

That move back to the States put me back into the work mode. Being at USF is also keeping me on my toes. I have to be responsible for everything I say. If I am telling a student, "Hey, you gotta practice," I gotta be practicing, too.

You're still in album mode, too.

The album, being thrown into these jazz festivals with Houston and all these guys. I don't have the option to relax. I have to push myself mentally, technically. It gets frustrating and scary getting thrown in. I did Newport Beach Jazz Festival a couple weeks ago, and all of a sudden I was in the same room as these legends that I used to listen to as a kid. There was that mental thing where you have to treat the situation as if it were normal, stand up to the test, and play your best.

I was gonna ask you about Buenos Aires, from the outside we romanticize that it, but could you talk about why you left? Why you felt like you weren't growing?

It was just the last few years, and I've felt it before, so it wasn't just Buenos Aires. Something — my body, or God — was telling me to go and that my time there was done. I was with good friends. I was getting the scene, learning Spanish. I was having a blast, it was incredible. Then, starting to tour and getting more popular down there. It was great, but I guess it got to the point where I knew I wasn't being pushed the way that I knew my friends were being pushed back in the State.

I felt that ceiling, and I looked around and said, "OK, this trumpet player next to me is amazing, but he's playing the same gig that I'm playing." I felt that ceiling. I realized that I wasn't going to get much further. That was a realization that I needed to move my environment.

I never felt like Buenos Aires was hell. I loved almost everything about my experience there: The people, food, nightlife, history, culture, music. etc. And I still have a lot of close ties, including my wife who's from there. We try to go back every year to visit, probably this July. I did get to the point where I needed to move on and be close to my family and give myself a push as far as my growth. It was a hard decision because I loved it so much.

So you did it all. Jazz camps, school, cruise ships eventually get you to this not as cheesy and easy Glenn Miller gig and relatively more relaxed Tommy Dorsey gigs. You went to China, and then Argentina for eight years and have put roots down here during your studies at USF. Why Tampa Bay? Was it really just Nate Najar’s enthusiasm, weather and family?

I lived in Pittsburgh. It was great, I had friends there, and I was playing in an original group. But I couldn't get more gigs than that, I didn't feel welcomed into the scene. That was of that sensation of, "OK, maybe I shouldn't be living here." So I tried another place. It's the same way, in reverse, coming to St. Pete.

I came here to visit my sister who lives in St. Pete. There I met Nate, who introduced me to John Lamb. He also introduced me to Buster Cooper. That right there is enough to be like, "OK, wait a minute. This is a different kind of place."

Yeah, Buster is obviously gone, but there is so much going on here.

And it just kept happening. Not just people I've been listening to for years. Great, young musicians. A vibrant scene and culture. That you can't find in many places. It's funny, when I came to Florida I thought that the big places, I thought, for jazz, would be Miami, Tampa and Orlando. I think what I realized is that St. Pete has more of that open jazz culture and appreciation. That kind of drew me to it. I can go to the beach, hang out with my family, and it ended up being this thing that time and time again would prove to be a great place to live and develop.

You obviously decided Berklee wasn’t for you. You went to Youngstown, and you’ve talked about the Rutgers thing. Thinking about young jazz players, maybe like Jason Charos who is at the Frost School in Miami, do you think that making a living playing jazz is harder for kids these days?

That's a good question. Honestly, I don't really know outside of my experience. It's hard any way you slice it. One thing I've always tried to do is to say that, "OK my background and love is jazz, but I am also a trumpet player. I love playing the trumpet, and being paid to play it." I think there are a lot of young students — and I am guilty of this, too — who think, "I only want to play jazz, and that's all I'm concerned with." That's extremely hard to do, especially in this world and especially when you're just begining. I always encourage young musicians, everyone really, to be open to playing a rock gig, or a funk gig, whatever, they're all learning opportunities. And when it comes down to it, you're playing your instrument.

I remember someone telling me that they feel like they sold-out because they were playing in a wedding band, and I said, "Man, you're playing your instrument. You can't sell-out if you're still playing your instrument. If you put down your instrument, then we can start talking about selling out." I still play gigs, other than jazz, but I do always put my main focus in jazz.

What about the publishing aspect of making art? Anything you can impart?

Well, I'm still learning about rights to music. Houston was helping me out, and so has Nate. I remember being in the studio — and I have three originals on the album — I just wrote 'em up, recorded 'em and that's it. And Houston said, "OK you have these registered, right?" And I said, "Nah." And he looked at me like I had just cussed him out. He couldn't believe it. He said first thing you need to do is get your music registered. He gave me all the famous stories of Duke Ellington, Irving Mills, all the guys who got screwed over on rights and royalties because they didn't make that certain step.

If I'm uncertain about things like publishing, rights or royalties, I ask someone that knows, that I can trust. Usually there's someone around or nearby who can answer all those questions.

Bad teachers are one way of ruining a kids dreams, but what do we say to young kids reading this who may feel like a future in jazz is out of reach due to familial support or financial constraints? What if that kid can’t imagine a life without jazz but is confused about how to make it happen?

I was so fortunate. My parents came to see me play last night. They supported me from day one and still support me. Before it was financially, and it's always been being there for me emotionally. That's something I've been fortunate with. I've had bad teachers, but I've been fortunate to realize that I can't afford to get caught up in their bad vibes. I have to focus on the good teachers and their good vibes.

Something I did on my own, that I think someone, no matter the circumstances, can or should be able to do is go out and check out live music. Talk to the musicians that they aspire to be. I remember when I was about 16, I was fortunate to have a couple of friends who were just as adamant about being a jazz musician as I was. On our own, we'd borrow someone's mom's car, and we'd figure out how to get to the café that so and so is playing at, or the jam session that we know we could get in without having to show ID. Places where we could ask to sit in. Bring our real book, fake book, whatever, with a music stand. That was the begining of us throwing ourselves into a situation.

It wasn't just relying on schools or classrooms where we could be listening to a bad teacher. Depending on parents who were financially or emotionally available to help us. That part of it, I think, young musicians can do on their own. Check out live music. There's a lot of free stuff. There are a lot of things were young people are allowed. There are a lot of possibilities. You may have to figure out how to get there, but there's always a way.

What bar were you having conversations with Nate at? Your brother in-law was bar manager...

That was Horse & Jockey in South Pasadena. He's still the bar manager there. That happened over some beers, those conversations, right at the bar. That's still a magical place. We all play there. John, myself, Nate and Bryan, he's the singer. We all play there once a month. We don't look at it as just a gig. We look at it as this chance to hang at this special place that kind of brought us all together. That place was responsible for a lot of introductions.

You’ve obviously got the Miles tribute band, but many have referred to some of your melodic ideas as “unpredictable” — do you agree? Where do you think you picked up that tendency?

That's funny because I know it's a compliment, but it's strange for me to hear. Obviously, coming from my own brain, it's predictable. I'm playing what I'm hearing. Sometimes I think, "Oh, I'm playing this again" because I'm hearing it again. I get annoyed with myself because I think it's too predictable. I've done Miles tributes, Louis Armstrong tributes, and each of those involves a preparation process where I spend the month leading up to it just getting obsessed with that individual's music and style. You integrate their approach to playing, their style, in your own playing. Maybe, I think, what happens is I mix them up, randomly, sometimes. I play a lot of blues-oriented sounds, but then someone like Miles Davis in certain eras of his playing wasn't plating blues. I like both approaches. I like to mix it up. Maybe to some people it sounds unpredictable.

Does turning 40 freak you out?

Reaching 40 doesn't really bother me. I freaked out when I turned 30. Fortunately I learned that age has nothing to do with most things.