Walter Lee Younger is seething. He’s had the same menial job for years, and he’s got nothing to show for it. He and his family rent a rundown, roach-infested apartment in Chicago’s Southside ghetto, all five of them jammed into two tiny bedrooms, with a shared bathroom down the common hall. Ruth, Walter’s wife, takes in ironing. She’s just discovered she’s pregnant with their second child.

Walter Lee Younger is the frantically beating heart of Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun. First performed almost 60 years ago, it remains the quintessential stage play about the urban African American experience. American Stage’s production is dark, dramatic and, at times, disturbing.

Walter, desperately wanting to make things better for his family, describes his future as “a big, long blank space full of nothing just waiting for me.”

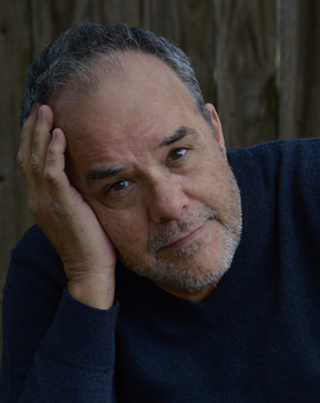

The heat given off by this play is intense. As Walter, Enoch King commands the stage and dominates every scene he’s in, which is nearly all of them. He rages, he cries, he dances and he laughs. He bellows and he whimpers. Yes, the Younger family is poor and black, and poverty and race deal them some ugly cards, but in a way, Walter is everyman. He’s Willy Loman. He wants his life to mean something.

“I'm 35 years old, I been married 11 years and I got a boy who sleeps in the living room,” he says, “and all I got to give him is stories about how rich white people live.”

As the story begins, Walter’s mother Lena (Fanni Green) is waiting for the mailman to deliver a check — the payoff from her recently deceased husband’s life insurance policy. In fact, everyone’s waiting for that $10,000, more money than any of them has ever seen. They all have different ideas about what such a boon will do for the family.

Walter’s idea isn’t exactly a get-rich-quick scheme, but it involves some risk, and he can’t convince Ruth (Sheryl Carbonell), or Mama, or his headstrong young sister Benny (Kiara Hines), that it’s a solid investment. And that’s driving him crazy.

Act II is nothing short of heartbreaking. Desperation drives men to do things they normally wouldn't consider.

The themes that run through A Raisin in the Sun — racism, poverty, betterment, pride and a burgeoning interest in one’s true cultural heritage — have become familiar in the six decades since the play first appeared. Hansberry’s words are sheer poetry, which makes Raisin a riveting experience in and of itself, even if it seems, at times, a little dated.

Here’s the thing about that: I could not shake the feeling that I’d seen some of these characters before — and then it hit me that television, that inspiration-free clone of stage and screen, has had 60 years to photocopy the kind-hearted matriarch who just wants to keep her family together, the gossipy neighbor whose every utterance is a thinly veiled dig, the friend who’s something of an uppity Uncle Tom, and the friendly white visitor who turns out to be a racist villain.

The way American Stage's theater is constructed, with the seats all facing the stage and rising like (comfortable) bleachers, can make a single-set show like A Raisin in the Sun feel like the taping of a TV episode. Every once in a while, especially in the show's few lighthearted moments, I felt as if I were watching Good Times or even The Jeffersons.

That's not to denigrate this groundbreaking work, or the performances of these exceptional actors. Carbonell, Hines, Green and young Elijah Jordan, playing the Youngers' 10-year-old son Travis, are for the most part brilliant. Supporting players Patrick A. Johnson (as Benny's Nigerian friend Asagai) and Dee Selmore (sharp-tongued neighbor Mrs. Johnson) turn in solid performances.

There were a few hiccups in the production I saw, an awkward line reading here and a falling prop or piece of set there, but the three hours went by like lightning, I was so involved in the story.

I came away awed by the power of good acting — thank you, Enoch King — and with a renewed appreciation for the transformative power of great storytelling. Thank you, Lorraine Hansberry.

Bill DeYoung is the author of Skyway: The True Story of Tampa Bay’s Signature Bridge and the Man Who Brought it Down and the forthcoming Phil Gernhard, Record Man. Learn more here.