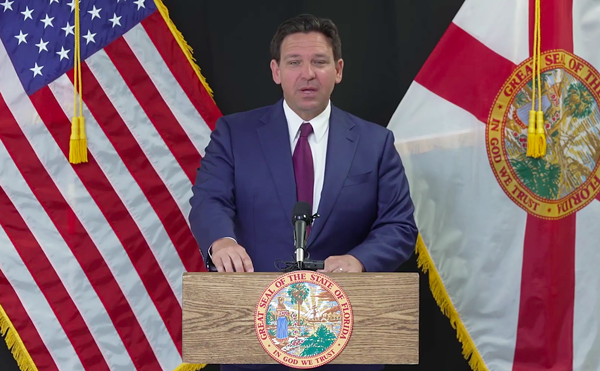

A letter signed by 44 faith and labor organizations—including the Farmworkers Association of Florida, the First Presbyterian Church in Dunedin (the governor’s hometown), and labor unions representing thousands of working Floridians—was sent to DeSantis’ office last week, following up on an earlier letter sent by another 43 environmental and labor groups the week prior.

“The bill harms Florida’s families of hardworking men and women whose labor is integral to our everyday lives,” reads the letter sent to the governor Tuesday, April 2.

“The bill also harms businesses that provide protections for their workers, risking their competitiveness in the marketplace,” adding that it “leaves hundreds of thousands of workers across the state with less oversight and protection, just as the state faces a labor shortage and significant losses to the state’s labor force.”

The groups’ call for a veto comes just days after the bill (HB 433) reached the desk of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, where it now awaits either his signature, or his veto. Under state law, Florida’s governor has the final say on whether legislation that’s approved by state lawmakers makes it into state statutes.

Florida’s state legislature, where Republicans outnumber Democrats more than two to one, passed the contentious bill on the last day of the state’s 2024 legislative session. The bill was passed largely along party lines, with just a handful of Republicans joining Democrats in opposition.

Sponsored by first-term State Rep. Tiffany Esposito, a Fort Myers-area Republican, the preemption bill would prevent Florida cities and counties from passing local laws that require businesses to provide any protections for employees against heat—including basic policies such as water breaks or education on heat illness prevention.

No city or county currently has such a law in place. However, the bill was filed for consideration by lawmakers less than a week after Miami-Dade County, facing industry pressure, delayed a vote on a local ordinance that would have established stronger heat protections for outdoor workers in the agricultural and construction industries, both of which carry high risks for heat illness and fatal heat exhaustion.

The vote was delayed to mid-March, conveniently scheduled after the end of the legislative session. According to WLRN, Miami-Dade commissioners officially withdrew the local ordinance from consideration last month, citing the state bill as the reason.

“The industry argument against local worker protection ordinances is that employers are already protecting their workers,” opponents wrote in their veto letter to DeSantis. “If this is the case, then, why are industry leaders concerned about a bill that can protect those workers whose employers may not be providing those protections? What is business afraid of if they are already doing the right thing?”

Johana Lopez, an outdoor worker in Apopka, called the bill an “injustice.” The 40-year-old works in a greenhouse most of the day, for a nursery. But even in the greenhouse, she and her co-workers are exposed to Florida’s heat.

She works anywhere from nine to 11 hours per day, picking and pruning plants that are shipped to Canada, North Carolina and local Home Depot, Publix and Lowe’s stores. She gets two 10-minute breaks per shift—one in the morning, another in the afternoon—plus a 30-minute lunch break.

She hasn’t experienced any health problems from heat herself, and has worked the job for seven years. But it’s a concern for her on the job, and she’s seen others around her faint from heat exhaustion.

“It takes a toll on the body,” Lopez told Orlando Weekly through a translator with the Farmworkers Association of Florida.

Heat-related deaths in Florida shot up 88% from 2019 to 2022, a report by the National Conference on Citizenship found, and are rising across the South amid record heat.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics has recorded hundreds of heat-related workplace deaths over the last two decades. The federal agency has admitted even their numbers “are likely vast underestimates.”

Over 2 million people in Florida’s workforce—or roughly 23%—work outdoors fixing roads, climbing power lines, gathering produce, building homes, and performing many other jobs essential for communities. While the federal government has guidelines for employers on keeping workers safe, there’s no federal or state standard in Florida on protecting them from heat.Over 2 million people in Florida’s workforce—or roughly 23%—work outdoors fixing roads, climbing power lines, gathering produce, building homes, and performing many other jobs essential for communities.

tweet this

Lopez’s employer offers them water, she said, and has first-aid kits onsite. But many of her co-workers are scared to visit a doctor or medical clinic for health issues, concerned about the potential cost. She also thinks workshops or training on preventing heat exhaustion—they currently get an annual training on pesticides—would be helpful.

The preemption bill, she said, is unfair and unjust. People who work in agriculture, in these fields, they're exposed to harsher labor conditions, she shared. The work itself is very demanding and exhausting.

But Florida’s business lobbying groups that backed the bill have significant pull with politicians in both major political parties, and they wanted this bill passed.

Records obtained by Seeking Rents, a Florida-based investigative newsletter, show the legislation was at least in part drafted by lobbyists for the business-friendly Florida Chamber of Commerce, a massive, deep-pocketed network of businesses across the state with political influence over both major parties.

The Foundation for Government Accountability, a conservative think-tank that’s historically lobbied for bills targeting the social safety net and child labor laws, is also implicated.

Draft legislation emailed to Rep. Esposito by a Chamber lobbyist in November (shared with Orlando Weekly) contained metadata identifying the author of the Word document as Chase Martin, a visiting fellow for the FGA.

Republican state lawmakers in support of the bill argued that state and federal law already set guidelines for protecting workers from heat dangers on the job, and that employers won’t unnecessarily put their employees in harms’ way.

Problem is, there is no mandatory standard to protect workers from extreme heat exposure, and a process currently underway to establish such a standard on the federal level could take years.

It could also be disrupted if President Joe Biden—who directed OSHA to come up with a federal standard in 2021—is voted out of office and his predecessor Donald Trump secures a second term. Trump rolled back worker safety rules during his time in the Oval Office, and has an extensive legacy of fighting for business lobbies at the expense of working people.

OSHA, the federal agency in charge of overseeing worker safety, can fine businesses that fail to provide a heat-safe work environment under its “general duty” rule, which requires employers to provide workplaces that are “free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm.”

But, without a federal standard, what counts as a hazard is somewhat open to interpretation and the rule is rarely enforced, worker advocates say.

There's a capacity issue. According to OSHA, the agency has just about one compliance officer for every 70,000 workers in the country, and state and local government employees in Florida aren’t even covered by their rules. Unlike a number of other states, Florida does not have a comparable state agency.

Some Republicans saw Esposito’s bill as protection from overregulation. “I don’t think we need a nanny government standing over any person who might get too hot today,” said Central Florida Republican Sen. Dennis Baxley, who’s term-limited from seeking reelection this fall. “It’s over-regulating,” he added during debate on the bill.

Opponents also warn that failing to take action on workplace heat exposure could be costly — landing a sucker-punch to employers where it really hurts. Lost productivity, driven by heat-related illness and injury, is estimated to cost more than $4 trillion annually by 2030.

Legislation filed by state Democrats in recent years to establish stronger protections from heat exposure for outdoor workers has languished, despite action from the state legislature to do so for student athletes.Lost productivity, driven by heat-related illness and injury, is estimated to cost more than $4 trillion annually by 2030.

tweet this

In 2020, Florida enacted a law meant to help protect student athletes from heat-related illness, following the death of high school football player Zachary Martin, who collapsed on the practice field and died due to heat stroke.

Florida’s House Bill 433, preempting local governments from establishing stronger heat protection policies for workers, also undercuts working people in other ways, too.

It also prevents local governments from passing what are known as “fair work-week laws”—requiring employers to give their employees their schedules a week or two in advance—and preempts local “living wage” ordinances, effective Sept. 30, 2026.

Living wage ordinances are local laws approved in some communities across the state that help to ensure employees of government contractors are paid enough to afford the area’s cost of living.

These ordinances essentially establish a wage mandate for employers that enter into contracts with local governments. Some policies also award preference in the process of choosing a contractor for contractors that offer better wages or benefits for their employees.

The bill’s preemption means that, effective Sept. 30, 2026, those ordinances are no longer enforceable. Thousands of contracted workers – from airport baggage handlers, to janitorial and sanitation workers — could see their wages cut as a result.

Florida Rep. Esposito, herself the president of a regional chamber of commerce Southwest Florida Inc, didn’t bother denying this. “Could wages go down? Maybe,” she said during the bill’s first committee hearing, where public comment on the bill was cut. “It’s up to the prerogative of the employer.”

She said the goal of the preemption was to “protect taxpayer dollars.”

“When we artificially inflate wages by putting mandates on private employers … all it does is make things more expensive,” she said during a committee hearing for the bill.

The Chamber of Commerce and other business lobbyists have been lobbying lawmakers to do this for years.

The ban on local policies establishing workplace heat protection policies was something of a twist this year. Although, not one without precedent.

The state of Texas last year passed its own bill — dubbed the “Death Star Law”—that, among other things, similarly blocked city governments from requiring employers to adopt mandatory worker safety policies, like water breaks. That bill went into effect Sept. 1, 2023 despite being declared unconstitutional by a state district judge.

If signed into Florida law, the preemption of workplace heat exposure requirements and predictive scheduling under Florida’s House Bill 433 would go into effect July 1, 2024.

The preemption of local living wage laws—or other policies that require local governments to give preference to contractors that offer higher wages, benefits, or heat protection policies—is effective Sept. 30, 2026.

This post first appeared at our sibling publication Orlando Weekly.

Subscribe to Creative Loafing newsletters.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter