CORRECTIONS: This story contains information that was omitted from an earlier version. Those passages are indicated by asterisks (*) in the text.

A year ago, T.D. Allman’s much-anticipated Finding Florida: The True History of the Sunshine State was published to a mostly positive reception. The 500-plus-page opus, which covers half a millennium from Ponce de Leon’s alleged Fountain of Youth to the death of Trayvon Martin, garnered a National Book Award nomination and was named one of the best nonfiction books of the year by Kirkus Reviews. But its reception in the Sunshine State was much chillier, with one of the harshest slams coming from USFSP history professor emeritus Gary Mormino in the Tampa Bay Times’ Sunday arts section. A separate story appeared weeks later in which the Times’ Jeff Klinkenberg and Craig Pittman listed factual errors in the book that ranged from glaring (Allman said St. Petersburg was the Pinellas county seat, not Clearwater) to debatable (he wrote that the Ku Klux Klan and the Mafia united to break Ybor City labor unions, a point on which historians disagree).

“Beware of subtitling your book ‘The True History of the Sunshine State,’" wrote Klinkenberg in an email to CL. “When you do that, you are inviting lots of knowledgeable people into reading your book closely.”

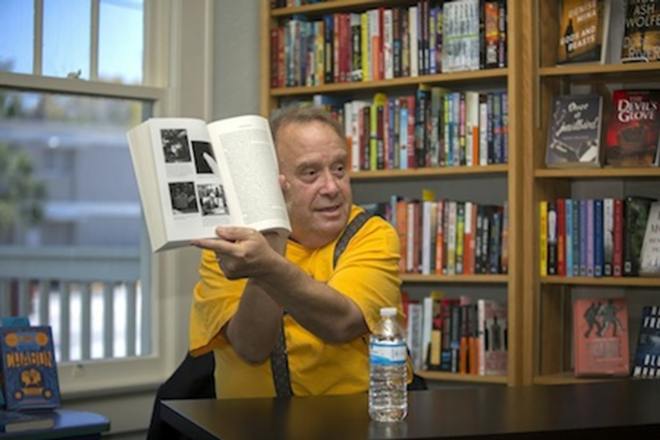

I catch my first glimpse of the 69-year-old author as he gingerly descends the staircase at a quaint downtown St. Pete hotel that calls itself America’s Best Inn. He was between appearances promoting the paperback release of Finding Florida — earlier he had appeared on WMNF radio, and in a few hours would be off to Brooksville. Then it would be back to St. Pete, then Sarasota and Tampa — all within a space of 48 hours, all part of the traveling road show that is T.D. Allman, an engaging raconteur who is ready on demand to deliver his soliloquies on the state of Florida.

Allman has enjoyed a long and illustrious journalism career, after graduating from Harvard in 1966 and volunteering for the Peace Corps in Nepal. Foreign reporting followed, with stints in Cambodia, Columbia, Libya, Thailand, India, the Middle East, El Salvador, Haiti, Ethiopia during the famine, and Tiananmen Square — 90 countries in all, for publications like the Washington Post, Harper’s, The New Yorker, The Nation, National Geographic and Vanity Fair.

I ask him to talk about his experience rescuing Vietnamese massacre victims in Cambodia in 1970, which reportedly led to his work being banned from the Washington Post.

He begins the tale by bringing up Elliot Richardson, best known for resigning as Richard Nixon’s attorney general during the Watergate saga after he refused to fire Archibald Cox, the special Watergate prosecutor. Allman said that, when he met Richardson, “I asked him if it was hard to resign and he said no, because there was no moral choice — and it was the same way with me and Cambodia.”

After he’d made two trips to pack as many critically wounded and bleeding victims as he could into in his car, a reporter at the U.S. Embassy that night asked, “Are you a journalist or an ambulance driver?” His colleague, war photographer Denis Cameron, then knocked out the offending journalist. “Of course my duty is to human beings,” Allman says.

In 1987, Allman wrote Miami: City of the Future, in which he took on the myth that it was “Paradise Lost,” and presciently argued that the multicultural metropolis was a harbinger of America’s future. More work overseas followed, before he embarked upon Finding Florida, a nearly decade-long undertaking to debunk the myths that he says have taken hold in the state, choosing instead to focus on its history of racism and violence.

While the book has definitely been a commercial and (mostly) critical success, the questions raised by Times reporters Pittman and Klinkenberg a year ago about the accuracy of his reporting still rankle.

“Their behavior has been unethical, disgraceful, vindictive and dishonest,” fumes the author as we sit in the diminutive lobby of the hotel. He’s dressed quasi-casual, wearing a blue blazer with a red handkerchief flowing out of his left breast pocket. Later he doffs the jacket, revealing a blue Miami t-shirt incongruously paired with suspenders. “They set out to discredit my book, and they failed.”

The one-two punch of the negative review and the story on the errors undeniably infuriates Allman. But, truth be told, they weren’t the only Florida reviewers who came away less than impressed by the book.

“This is selective history,” wrote James Clark, history professor at the University of Central Florida. “What is most troubling about Allman’s book is that it could have been a landmark publication. Allman is a powerful writer, and had he been willing to do more research and provide a complete picture, this could have been an outstanding book."

“Interesting and infuriating,” the Miami Herald’s Susannah Nesmith wrote. “Sometimes shrill and tedious.”

Allman alleges there was an orchestrated campaign by the Times to bring him down, and cites the fact that Mormino was circulating his review in advance of its publication to a few other history professors, including Rollins College professor Richard Fogelsong, who then alerted Allman about the as–yet unpublished takedown.

When the author learned of that, he wrote to Collete Bancroft, the Times’ book editor, accusing Mormino of “attacking my character” behind his back, which risked causing him “professional and financial damage.” (All emails that we quote from were provided by Allman.)

When contacted last week, Professor Mormino acknowledged that he had circulated the unpublished piece, saying he was unsure if he had been too negative and wanted to get some feedback from some colleagues. In retrospect he says he’s embarrassed he did it.

Shortly after Mormino’s piece was published, Allman then received an email from Pittman listing the 16 factual errors the Times had found in the 500-page book. Some of those were not disputed by by Allman or his editor, but there were others that they questioned (Pittman chose not to comment for this story).

Allman responded with a two-page letter that he hoped would be published in its entirety in the paper, but in an email Pittman retorted, “I can’t see us publishing in its entirety a two-page letter from anyone short of the president or the pope… however, there appears to be quite a lot of space available on the Internet.”

*The Times did go on to publish Allman's letter in its entirety online.

*Pittman, contacted for comment on this story by CL, responded by email, “My editor said I should just tell you we stand by our story & haven't seen any reason to do otherwise.”*

Allman reached out to academic colleagues to come to his defense. One of those was Yale Professor of History Glenda Gilmore, who wrote to Times Enterprise Editor Bill Duryea questioning half of the listed mistakes as being “historical and interpretive arguments points.”

“In these eight points, Mr. Pittman is either simply wrong, distorts Mr. Allman’s meaning, or argues against something that Mr. Allman did not say. After 50 percent of the arguments vanish, is there a story here?” she wrote.

The Times believed there still was and went ahead with their story.

While that was happening, Allman continued on his national book tour, but thoughts of what the Times had done were never too far from his mind. He wrote several entreaties to Paul Tash, the paper’s publisher, who infuriated Allman further by refusing to acknowledge any of them. His final correspondence was on May 27, in which he once again laid out his bill of particulars against the paper, and again asked for an opportunity to respond in the paper to the Times’ criticism.

That never happened.

“I write to the editor of the Guardian, or the Bangkok Post, or the editor of the New York Times or the Miami Herald, and they answer my telephone calls and they answer my letters,” Allman says, adding that he believes the Times should do itself a favor and hire an ombudsman or readers’ representative — something that other publications like the New York Times and Washington Post employ.

USFSP’s Mormino says his problem with Allman’s book is his absolutism, as when he says novelist Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings came to Florida to make money growing citrus, or when he heralds former U.S. Senator Claude Pepper as an icon, without analyzing the arc of his public life.

“Rawlings probably did more to uplift the image of poor whites than any living author,” Mormino says. And of Pepper, lauded by Allman as one of the unreconstructed heroes in Florida history, Mormino says the former senator’s past was much more complicated, referring to how he once filibustered against a bill that would have made lynching a crime.

“Everything is in black and white,” Mormino says of the book. “Rawlings is complicated. Florida is complicated.” Other Florida-based bloggers have lodged similar complaints.

When told that some consider his vision of Florida too dark, his answer is that he does not deny the “tragic nature of existence.”

“You cannot understand Florida. You cannot understand America. You cannot understand yourself, unless you understand the tragic nature of history.”

Despite the controversy, Allman lives a good life, with homes in Miami, New York, and the south of France. Born in Tampa, he says that he realized the moment he was going to be a writer when he was 7 years old and in the second grade reading Dick and Jane books. And he said that it was in the Peace Corps that he learned that all human beings are to be treated equally.

Along with their published piece, both Pittman and Klinkenberg have gone online to further bash Allman. After Allman penned an op-ed in the New York Times last year, Klinkenberg posted online that the editorial was a “slightly toned-down version of an over-the-top book riddled with errors and misinterpretations pretty much debunked by historians who know something about Florida.”

In a separate email sent to CL last week, Klinkenberg compared Allman to Michael Moore and Ann Coulter, writing that they are both entertainers for their side. “Neither is a historian. They may or may not be careful with their facts. But I don’t think that’s their point. They are entertainers who like all of us are trying to make a buck.”

A piece published last week by the Palm Beach Arts Paper also merited an online comment by Pittman, who wrote “the book would have been better if he had gotten more of his facts straight,” followed by a link to the Times story regarding the errors he and Klinkenberg discovered.

In discussing his entreaties to Tash, I asked Allman via email about a former Times reporter’s interpretation of the battle between him and the Times — that Allman was particularly bitter toward the Times and to Tash because the editor serves on the Pulitzer Prize committee.

“Why are these people constantly projecting malign motives on me?” Allman responded via email. “They could have found out what was my motive in writing to Tash — outrage at their dishonesty — simply by responding to my letters. That also would have been normal courtesy, the way professional people operate. It was also their professional duty to respond, and they did not.”

Tash did not respond to our requests for comment.

So what does this all mean? Referring to the book’s positive reception in the New York Times and to its sales success, Klinkenberg surrenders, saying of Allman, “He won.” Nevertheless, many historians both amateur and academic will remain convinced he missed the mark.