The shaming of William Guevara began early on a summer morning. At 7:30 a.m., July 9, 2004, Guevara and his wife Judy were awakened by banging on their front door. Judy went to the door in her robe to find officers from the Tampa Police Department waiting to arrest her husband.

Officers gave Guevara little time to dress before handcuffing him behind his back. "They didn't even let me comb his hair," Judy says.

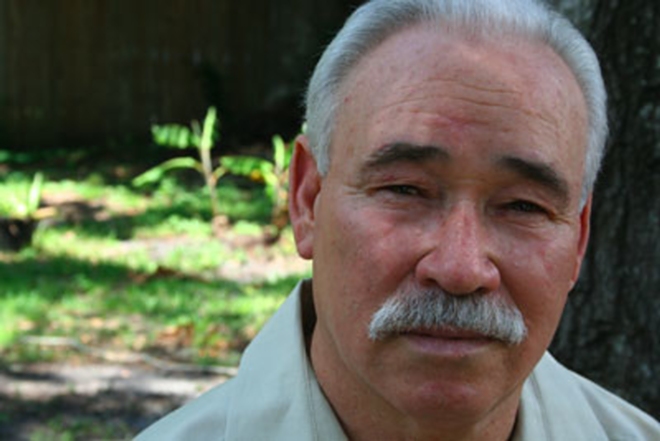

Two years later, Guevara still suffers from the arrest. As he tries to tell his story, he slumps forward, his voice breaking, barely able to utter a word. Tears fall from his eyes onto his guayabera shirt. His wife must speak for him.

Guevara is a small man, 60 years old, neatly dressed, with white hair and a moustache immaculately cared for. He doesn't look like a criminal. But on that July morning, he was treated like a criminal.

His accuser? Pro wrestling icon Hulk Hogan. In the star's eyes, William Guevara — who had cared for years for Hogan's elderly father and mother — was a thief. Police charged Guevara with third-degree grand theft, exploitation of an elderly person and fraudulent use of a credit card.

It was all a mistake.

William Guevara entered Hulk Hogan's world in 1998. He and his sons were working as caregivers for elderly people, running errands, fixing up homes, doing whatever was needed. Hogan's chauffeur, an acquaintance of Guevara, mentioned to him that the Hulk's father, Pete Bollea, needed a caregiver. (Hulk Hogan's real name is Terry Bollea.)

Pete Bollea was in poor health, unable to move without aid, and lived in South Tampa with his wife Ruth. Guevara met them and, with his two sons, began working for the couple. His sons were paid $15 an hour to care for Pete until his death on Dec. 28, 2001; William did not receive any payment for helping Pete, he says.

Guevara began working with the elderly 30 years ago in his native Puerto Rico, carrying on a family tradition that began with his father and continued with William's sisters, who went on to own nursing homes in Tampa. When he came to Tampa to live in 1995 (his second trip to the States after working as a farm laborer in Delaware for four years in the 1970s), he took jobs with his sisters as needed. He remembers one moment in particular that convinced him that he had a calling, a "gift from God"; a favorite patient died of a heart attack in his arms, and the experience reaffirmed his commitment to helping older people. He has usually worked for little or no money.

"The thing that people don't understand is that William is that way," Judy said. "He'll do anything for you without expecting anything in return."

His relationship with Ruth went even further; he not only cared for her, he came to think of her as part of his family. He has pictures of Ruth and Pete with his sons, and today, when he shows photos Ruth gave him of herself, his countenance brightens.

"She was like a mother to me," he says in Spanish. He says he was Ruth's paño de lagrimas, an expression that means that his was the shoulder she cried on. "Most people who do what I do, they let themselves be paid, but I cared. I only did good for her," Guevara said. "I treated her better than my own mother."

From time to time, he says, Ruth would give him $10 or $20 for gas money. He lives in the Lowry Park neighborhood in north Tampa; the drive to Ruth Bollea's home south of Gandy Boulevard is not a short run, but Guevara says he sometimes made the trip three times a day when Ruth would call for assistance. And she called often. Judy Guevara said in a written statement prepared for the lawsuit that her husband took Ruth to doctor's appointments, shopping trips and visits to friends. "He even soaks her feet in Epsom salts when needed," Judy wrote in her statement.

According to Guevara's next door neighboor, Juana Mondragon, his willingness to help without being paid was typical of him. Mondragon, 80, has known him for seven years, and says that Guevara brought her groceries and medicines and took her to the doctor while her son lived out of state.

"Anything I needed he would do for me and never with reproach," Mondragon said. "I would ask him, 'What do I owe you,' and he would say, "No m'am, nothing.' He was such a caring, responsible, honest person, there is no way he could ever have done what they said he did. He is a good man."

Hulk Hogan grew up in his parents' modest, 1,170-square-foot home on 3106 Paul Ave., graduating from Robinson High School. The working-class neighborhood south of Gandy is a far cry from Hogan's $6.4 million Belleair mansion, known to fans of the VHI reality show Hogan Knows Best, or the $12 million estate in Miami he purchased in April.