St. Petersburg griot Gwendolyn Reese grew up at 1305 Fifth Ave. S, in a cherished part of town known as Sugar Hill. In the 1970s, Interstate 175 bowled through her block, and following a nationwide pattern, leveled a Black community. Reese has given her adult life to preserving the landmarks and memories that survive in south St. Pete.

"The church where I was baptized and married is no longer there," Reese explained at a recent forum, speaking in her carefully measured alto. "I can tell my children my story, but I cannot take them and actually show them the buildings."

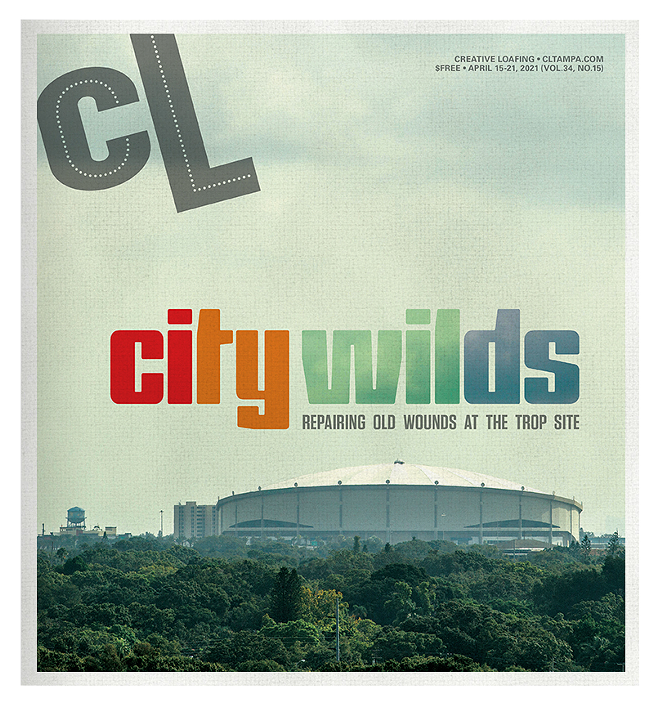

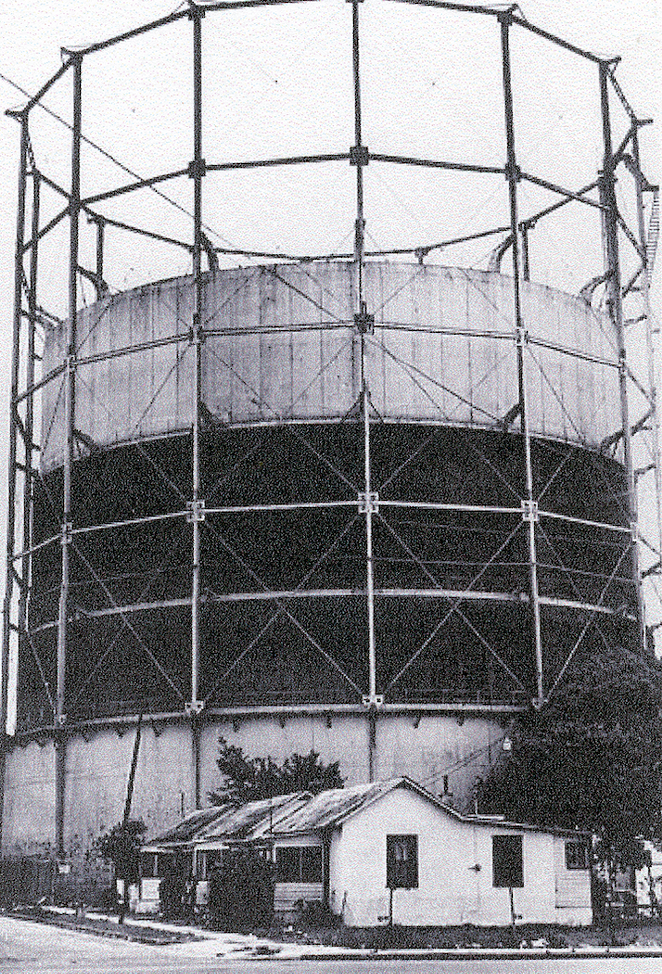

Stories of the adjacent Gas Plant neighborhood follow the same refrain. Black space got replaced by white "urban renewal." Promising light industry, the city razed the 86-acre site around what is now Tropicana Field, where Booker Creek still flows. The story has been told many times: how the city bulldozed over 285 buildings, 500 households, and at least nine churches.

Virginia Arno, a FAMU graduate in her 80s, holds roots in the former neighborhood that reach back generations. "My mother and father, aunts and uncles, grandparents" all lived close by, Arno said; "we were very close knit." Roslyn Graham, who grew up where the dome now sits, on Fourth Avenue and 14th Street, describes similar loss, "like ripping a family apart."

The outrage, then and now, is palpable.

"When you went into this area and moved all the people," City Council member David Welch noted in 1982, "you said you were going to rehabilitate and create jobs." Instead the city built a ballpark, for a baseball team that did not yet exist. Welch, the second African-American ever to serve on City Council, reminded his peers of a "moral obligation" to fill broken promises.

No one denies a fundamental truth, the moral obligation David Welch described 40 years ago still stands. There is a check due with interest.

Last week, St. Petersburg officially trotted out four proposals that would transform the asphalt wasteland surrounding the Trop. The city has even set up four showrooms to collect community input on the redevelopment. The end result will probably run to a billion dollars, with the public contribution from a tax fund created to remedy "blight and poverty in south St. Petersburg." The city promises to "get it right." But the mechanisms for repeating past mistakes are also in place.

The sheer weight of bureaucracy dulls our senses. Actually reading the four proposals presents a daunting task—over 800 pages of slick graphics, with nifty gimmicks (a roller skating rink!), lofty ideals and rhetorical fudge,and financial projections that would stymie a forensic accountant. The proposals can be evaluated for quality of design, fiscal viability, the promise of delivery, and history of work with the city (or red-meat cronyism). Insiders remind us that architectural renderings rarely match the built realities. Priorities switch around, as intentions play out, for better or worse. The city has held countless public forums on the site, but what lay person is going to follow Ariadne’s red thread through this procedural labyrinth?

The starting RFP, or Request for Proposals, establishes a framework for contradiction. The "Twenty-One Guiding Principles of Development" outline a public-private collaboration that will "honor the site’s history and provide opportunities for economic equity and inclusion." The project should value diversity, small business, and "authenticity." The design should also incorporate a fancy hotel and 50,000-100,000 square foot convention center, two things that rarely yield "equity" or "authenticity."

Given the past wrongs, and mobilization of funds created to remedy “poverty and blight,” it bears asking: which of these proposals best serves the city’s most pressing needs?

So I took it upon myself to scale the mountain of online materials. I spoke with city employees, stakeholders and cynics, as well as public officials, past and present. I propped open my eyelids through the first of the public presentations, on Zoom, fighting the temptation to slug back a second glass of wine. And with an eye as to how the city might repair past damage, I offer my own outsider's review.

The proposals

Unicorp, an Orlando-based firm with deep ties to St. Pete public works, specializes in "destination driven" development. Leading a team that includes Zyscovich Architects, with a heavy dollop of Disney, Unicorp presents Petersburg Park. Little in the 200-page proposal (which pumps the conference center up to 70,000 square feet, plus the requisite hotel) addresses past controversies, suggesting instead that old wounds be healed with greenspace. "What the city wants," principal Bernard Zyscovich explains, is "something magical in what is now nothing more than parking lots."

We have a problem here of outlook. Unicorp bills itself as a "market leader" in developing "Class-A apartment complexes." If "getting it right" is the goal, repairing the damage leveled by a century of systematic racism and inequality, the city will need more than upscale housing, broad hopes for a park, and an urban planner’s Pixie dust.

Portman-Third Lake (PTL), based out of Atlanta, embodies corporate caché. Portman Holdings has "raised and deployed over $10 billion and developed in excess of 65 million square feet" of prime real estate since its founding in 1957; Portman Residential specializes in apartments boasting "premier location, attractive design, luxe finishes" and "spectacular amenities." Its team includes Ken Jones (former deputy chief of staff for less-than-progressive Mississippi Senator Trent Lott) and Echelon's Darryl LeClair, who developed the Carillon office park.

The group mobilizes serious capital, and while PTL's short pitches emphasize community and connection, the proposal hints to a corporate bait-and-switch. "The greatest way to acknowledge the pre-Tropicana Field historical context," PTL maintains, "is to rebuild and reintroduce a prosperous community that was previously displaced." (The term “high quality” appears almost as much “affordable” as an adjective for “housing.”) Jones points out that developers need "to talk to the community" and "get people engaged."

All good.

But the Trop site is not an office park. In an April 5 public presentation, the four white guys from PTL did not offer any pretense of diversity. This project calls for outreach. (“The developer will implement a strong community outreach program, seeking input from all community stakeholders,” the RFP states.) Given the site’s history, is this the best group to conduct difficult conversations about inequality and racial healing?

The city could simplify its process by eliminating those first two proposals. Perspectives are off. Cut the field in half.

A group calling itself Sugar Hill Community Partners (SHCP) takes its name from the prosperous Black neighborhood buried under I-175. Of the four proposals this plan most deeply reflects upon the recent past, and maybe because of that, it deserves the closest scrutiny. St. Pete locals will recognize the imprint of Sarah-Jane Vatelot's thoughtful study, “Where Have All the Mangoes Gone?” As Vatelot and others have noted, the area's Black community once enjoyed fruit trees, providing local youths with snacks for the taking. From this symbolic detail comes Sugar Hill’s promise of a History Walk, pocket orchard, performance spaces, workforce development, and affordable housing. It engineers a full-blown social vision.

Clearly this team has mapped out the spatial heritage, though it bears noting, St. Petersburg has a bad history of falling for Big Promises. Behind Sugar Hill’s veneer of the local (as with the other groups) lies a formidable operating team, one that seems to specialize in high-developments flanking stadiums and “revitalized” urban cores. Phase One of the Sugar Hill Project includes a capacious 650,000-square-foot convention center, which would be almost doubled in the fourth and final stage. A 500,000-square-foot marine-tech campus promises high-end jobs.

These were requests from the city, points 12 and 13 of the ”21 Principles.” More than any of the four proposals, however, Sugar Hill unravels around the cross-purposes of the starting RFP.

The team includes Blue Sky, a trusted local developer of workforce and affordable housing, but the problem of scale remains. Sugar Hill earmarks 35%-40% of housing at 80% area median income (or AMI), following a standard three-tier division(30%, 60%, 80%). The AMI for a family of four in Tampa Bay, HUD reports, is $72,700. The language of affordable housing is tricky, but the upshot is that without a specific commitment to the number of units set aside for folks who make around $12/hour, it’s still hard to see how the needs of the poor are being prioritized.

Run the numbers this way. My wife and I raised a child in a 850-square-foot, south St. Pete bungalow. The convention center (after stage four) would total one million square feet. According to the calculator on my phone, our little house could fit into this convention center 1,764 times.

Corporate daydreams trump real concerns. The city’s economic development office (not southside residents) wants a hotel and convention center, and in this light, the nods to local history seem more symbolic than substantive. Sugar Hill’s plan allows for a Black-owned microbrewery, as well as a "pebble beach," just a stone's throw from where the gas tanks leaked toxins into Booker Creek. So where will the mangoes go? Most likely, on the convention center’s LEED-certified roof.

The Midtown group, by contrast, does the best job keeping its eye on the prize. Avoiding the more complicated financials and social engineering, this Miami-based group (led by Alex Vadia) proposes a $60 million fee-simple purchase, paid as the project develops. Midtown emphasizes housing, with a promise of 1,000 units, and the partnership carries a weighty endorsement by Reverend Watson Haynes of the Pinellas County Urban League. Team members have worked with a similar site in Greenville, South Carolina (built over a former textile mill) and tucked the Durham Bull's baseball stadium into a similar tight setting. Locals will recognize names like Tim Clemmons of PLACE Architecture, as well as arts impresario Bob Devin Jones. The landscaping plan, from the shop of MacArthur Fellow Walter Hood, is gorgeous—indeed, the only one that starts from the creek's geologic base. By holding the convention center to a modest footprint, simplifying finances, and targeting our most pressing needs, Midtown offers the best shot for TIF money (tax increment financing) to serve the purposes for which that fund was designed.

A fifth option

But there is one more option. We wait.

Several key questions remain. When pressed with concerns about who this project serves, the mayor’s office points to six years of visioning and public engagement. On the need for a convention center, officials cite market studies and “economic development partners”—to the Chamber of Commerce, not the people. The rationale for low-paying, part-time jobs with a convention center and luxury hotel echoes the false promise of “light industry” 40 years ago. “ ...but a convention center is not something the City of St. Petersburg is necessarily focused on. It is just an idea, and one supported by some of the development teams,” Kriseman’s office told Creative Loafing Tampa Bay.

Given the Gas Plant’s prior uses, clean-up could easily run over budget. When asked what would happen if Booker Creek’s remediation gobbles up TIF funds, what other branches of the project would suffer the cut? The Mayor’s office noted that the environmental remediation of the site was done before the Trop was even built in the late ‘80s. Kriseman’s office said there is $75 million in money for infrastructure on the site, and that would include further environmental remediation, should the city need it.

“ ...some of what is used for that will depend on which developer is selected. One developer, for example, has committed $94 million for infrastructure, so should further remediation be needed, we could presumably use that, or some of that money as well,” Kriseman’s office said.

And let’s not even bring up the Rays.

Kriseman’s office has repeatedly taken the stance that this project will transcend many mayors over many years. “As you’ve heard Mayor Kriseman say, he is going to continue his work until the last minute of his last day in office,” a spokesperson said.

Still, as Terri Lipsey Scott asks, "what's the rush?" The Tropicana Field development offers a “generational” decision. Even the more worthy proposals (Sugar Hill, Midtown) leave serious doubts.

Maybe the best choice, right now, is none at all.

Thomas Hallock is Professor of English at the St. Petersburg campus of the University of South Florida, where he teaches early American literature and nature writing. He frequently takes his nature writing classes on walks up Booker Creek. See additional resources and quotes about the Tropicana Field redevelopment project below.

Thoughts on the Trop Site Redevelopment

"We have to acknowledge that damage has taken place, that the ancestral damage has been done. And then we have to move forward with that sensibility in mind. We have to acknowledge the soul, and just placeholders .... You can never replace what was there. But with knowledge of the current times, you can commemorate and energize it."—Bob Devin Jones (Artist Director & Co-Founder, Studio@620)

"This is another scam [in which] Black people are going to be thrown under the bus .... This is the second time. Under the pretense that light industry was coming, the city convinced people to sell our property. They lied to us. It was a scam from the word go. They were lies from the beginning and they are lying now. It is economic development for the white community at our expense.—Chimurenga Waller (National Director of Organization, African People's Socialist Party)

"I fear a repeat of what happened to the Gas Plant district. If we don't know and analyze what happened, we are doomed to repeat it .... We have to be careful that we do not fall into a trap again. Community should be first. This should [provide] industry for the whole area. The money has to come back. What we can do is keep the money inside. We can rebuild a thriving Black community—we still are a thriving community. We want to relieve the economic pressure of oppression."—Jabaar Edmond (Film maker & Activist)

"It is premature to decide [on a Trop site proposal]. The dynamics can change drastically in two years. The process is overreaching and can potentially limit opportunities for the next administration. The Pier represents the most recent major project undertaken by the City, where extraordinary funds were expended for a plan that was ultimately scrapped—as a result of a new administration's vision. Expediting this process creates yet again an opportunity for broken promises. Have you learned nothing from the last time? We're navigating the same process with the same compass .... We have to be reminded of what has been lost and how we got here. Let's not be tricked again."—Terri Lipsey Scott (Executive Director, Dr. Carter G. Woodson African American Museum)

"It was a tragedy. These people had been neighbors and friends for a long time and they were dispersed. A lot of these people were elderly and they had to pick up and move. It's just not a really good feeling."—Virginia Arno (Retired Educator, Native of St. Petersburg)

"It was like ripping a family apart. You knew you would never see people again .... I think it should go back to family, and family based, where our kids grew up together. Let's get back to our roots."—Roslyn Graham (Retired Business Owner, Native of St. Petersburg)

"This is a generational project, and as a Black native St. Petersburg resident, I want to make sure that we will be able to make good on promises that we've not kept before. We must make sure that the whole community—and specifically the Black community—is engaged and at the table."—Nikki Capehart (Urban Affairs Director, City of St. Petersburg

"I think people need to go into this asking the hard questions. It's easy to get excited about [the proposals]. But if the math doesn't work, it all unravels .... It's a great opportunity to connect the north and south parts of town. It's a great opportunity for justice. We just have to make sure that we do not make any promises that we cannot deliver."—Karl Nurse (City Council (2008-1018, St. Petersburg)

Unanswered Questions

The city of St. Petersburg, to its credit, has welcomed dialog and open exchange about the Tropicana Field site. After careful review of the four proposals, CL still had some questions. We presented these concerns (below, in slightly revised form) to Mayor Rick Kriseman:

- The city's Economic Development Administrator Alan DeLisle mentioned that in the event that the site requires additional environmental remediation, which is very possible given the Gas Plant's history. TIF funds could be used, as we understand, but isn't that money currently slated for other issues, including affordable houses? How do we move forward?

- In a previous interview, Alan DeLisle would not provide a direct response as to why a convention center and luxury hotel best serve the interests of restoring economic justice to the site. How will these projects close economic gaps in the city?

- In interviews with community members, we have rarely heard that “St. Petersburg needs a convention center/hotel." During the many public meetings, particularly among south St. Petersburg residents, when has the call for these projects come up?

- With only nine months left in his term and a "generational" decision on the line, is it within the best interests to keep this project on such a tight timeline?

Benjamin Kirby, Communications Direct for the City, responded for Mayor Kriseman:

- With respect to convention center space, the RFP asked for a four-star (or higher) hotel, with an integrated conference center consisting of 50,000–100,000 sq ft. That number was based off the market analysis performed by HKS [Architects]/RCLCO [Real Estate Advisors] during the conceptual master planning process in 2016. One proposal has gone far beyond that, with a proposed 650,000 square foot convention space, and did their own market/demand study to back it up.

- The idea of a hotel & conference center was discussed heavily during the master planning process by the public and our economic development partners (i.e. Chamber [of Commerce], Downtown Partnership, Innovation District, & CVB [St. Petersburg/Clearwater Convention and Visitors Bureau). It was also included in both conceptual master plans (with & without a stadium) .... [C]onvention centers and hotels bring lots of jobs and people to any site, but a convention center is not something the City of St. Petersburg is necessarily focused on. It is just an idea, and one supported by some of the development teams.

- With regards to the timeline, I would say it hasn't been rushed. We are in year six of the visioning process and public engagement related to the site. Going forward, this project will transcend many mayors over many years. As you’ve heard Mayor Kriseman say, he is going to continue his work until the last minute of his last day in office.

Learn More

- Any review of St. Petersburg's history starts with Raymond O. Arsenault's “St. Petersburg and the Florida Dream, 1888-1950” (1988)

- Rosalie Peck and Jon Wilson fill in many gaps with “St. Petersburg's African American Neighborhoods” (1988)

- Sarah-Jane L. Vartelot offers a plan for the Gas Plant, based on the past injustices, in “Where Have All the Mangoes Gone? Reactivating the Tropicana Field Site" (2019)

- “Voices of Booker Creek” (2020), edited by Anna Maria Lineberger, Dyllan Furness and Kelly Kennedy, includes a timeline and the transcript from a community forum about the Gas Plant neighborhood.

- The Nelson Poynter Memorial Library at the St. Petersburg campus of USF provides an excellent guide, "St. Petersburg African American History Resources," with linked articles.

Support local journalism in these crazy days. Our small but mighty team is working tirelessly to bring you up to the minute news on how Coronavirus is affecting Tampa and surrounding areas. Please consider making a one time or monthly donation to help support our staff. Every little bit helps.

Subscribe to our newsletter and follow @cl_tampabay on Twitter.